Foto: Banco Mundial

Foto: Banco Mundial

The theme of this year’s International Youth Day, “transforming education,” reminds us how important it is for all boys and girls to have access to education. In Africa, young women are over 1.5 times less likely than young men to be formally employed or undergoing education or training. Unequal access to educational opportunities, early marriage rates among young women, and responsibilities for unpaid care and housework are some of the factors contributing to this disparity.

Here we draw on the findings of the recent report on The Skills Balancing Act in Sub-Saharan Africa : Investing in Skills for Productivity, Inclusivity, and Adaptability and on data from the World Bank Gender Data Portal to present five facts about young women in technical and vocational education and training (TVET) in the region.

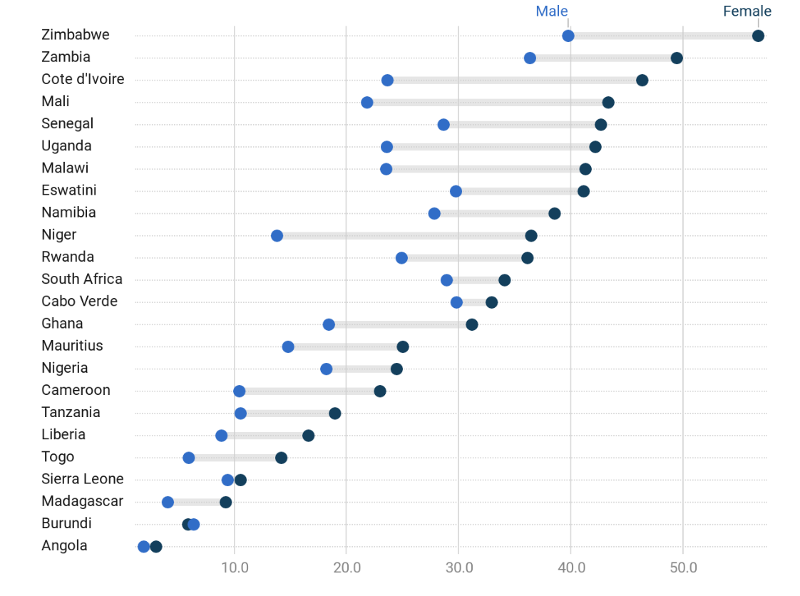

1. The school-to-work transition is hard for many African youth, particularly for young women.

Share of youth not in education, employment or training (%)

2. Formal TVET is small in Sub-Saharan Africa, and women are less likely than men to participate.

TVET is increasingly seen as a promising route for many young Africans who lack the foundational skills, means, or interest to take a more academic track. However, the formal TVET system in most countries in the region remains small in terms of both enrollment and public expenditure. In 2017, on average 5.9% of students in secondary education enrolled in vocational programs - not a large change from 2010 when it was 6.5%. These levels are below what would be expected given countries’ level of income and historical experience.

TVET levels are below what would be expected given countries’ level of income.

Correlation between TVET Enrollment at the Secondary Level and GDP per Capita over Time across Countries

The region clearly lags others: the share of male and female students in secondary education enrolled in vocational programs is 6.4 and 5.2%, respectively. In contrast, the share in Latin America is 12% for young men and 13% for young women and in the Middle East and North Africa the rates are 14 and 9%, respectively.

Share of students in secondary education enrolled in vocational programmes (%)

Across the board, gender gaps in TVET enrollment are significant. Enrollment rates among female students in secondary-level TVET are lower than those among male students in two-thirds of the 31 countries with data between 2014 and 2017. Further, gaps (to the detriment of women) appear to be wider in the countries with larger systems, suggesting that as systems expand gender gaps are likely to get larger in the absence of corrective measures.

3. Gender gaps in TVET tend to be wider in larger systems.

Share of students in secondary education enrolled in vocational programmes (%)

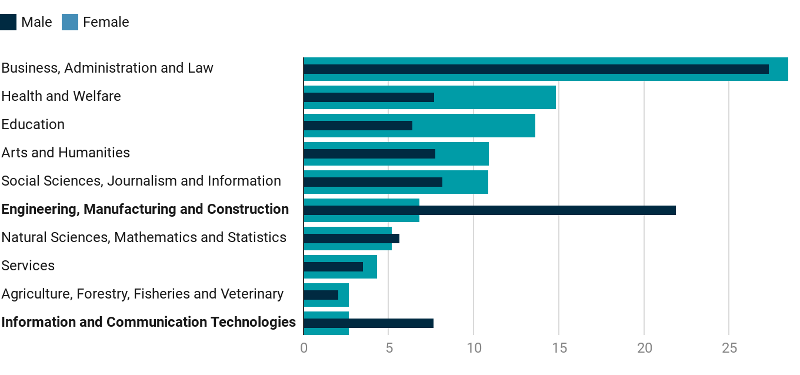

As in other regions, women and men in Africa enter very different TVET fields, with women often choosing (and being offered) skills training and occupations with lower average returns. As is the case in STEM higher education, the gender gap is particularly large in male-dominated fields, including architecture, ICT and mechanics. In Burkina Faso, women outnumber men in commerce, whereas men outnumber women 5:1 in the industrial sectors (mechanics, electronics, construction). These differences matter for future earnings. Women who cross into male-dominated sectors make as much as men and three times more than women who stay in female-dominated sectors (Campos et al 2015).

4. Women are less likely than men to study STEM careers.

Student enrollment per career program (%)

A lack of information about opportunities in male-dominated sectors, psychosocial factors, limited role models, networks and biased gender norms that start early in life are some of the factors that explain these dynamics. Often, TVET programs are not designed to accommodate family responsibilities. This affects women who bear household and childcare responsibilities (Cho et al. 2013; Glennester et al. 2011).

5. Young women are less likely to pursue TVET in more unequal societies

Way forward

As highlighted in the Africa regional skills report, TVET for TVET’s sake is, of course, not the objective. There are many challenges, but also opportunities to improve the quality and relevance of TVET in the region. While TVET seems to pay off for youth who reach this education stage, but who would not otherwise benefit from a university education (where there is large variation in returns), without improvements in quality its impact is limited.

A major challenge for TVET—and society more generally—is to overcome the barriers that keep women from acquiring relevant skills and accessing higher-productivity jobs. TVET not only has the potential to improve the school-to-work transition for girls, but also to promote the productive participation of women in the labor market, equipping them with the skills needed to undertake the jobs of the future or to help them “cross-over” to “male” fields where returns are higher. Further, TVET may help delay marriage and pregnancy.

For these reasons, improving access among women will require a policy package that addresses a multiplicity of constraints. This includes career and academic guidance and measures that improve access by making TVET provision more flexible.

Technology might also provide opportunities for closing gender gaps. It can enable access to information and services, help mitigate time and mobility constraints, and create job opportunities in new sectors. However, reaping the benefits of technology requires investments in a balanced skills portfolio that encompasses cognitive, socioemotional, and technical skills. In the case of TVET in particular, technological change—and other megatrends affecting labor markets and skills demands—highlights the importance of strengthening foundational skills in order to avoid too narrow specializations that then hinder graduates’ adaptability and long-term labor market prospects.

Join the Conversation