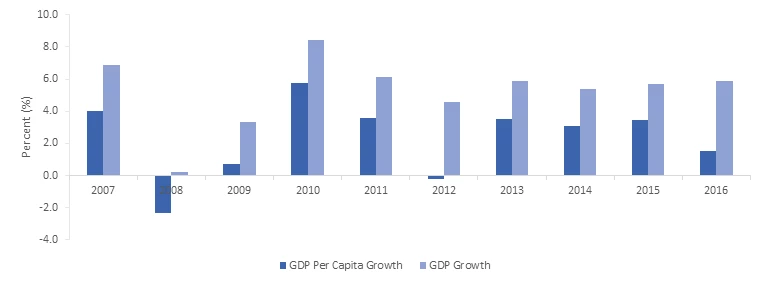

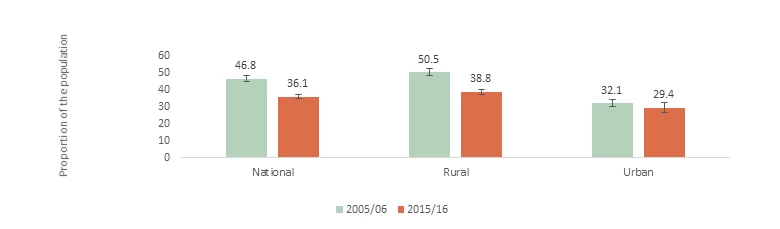

Kenya has been covered widely in economic news over the last decade, from the first large-scale application of mobile money to a vibrant technology hub in Africa. Indeed, Kenya experienced robust economic growth from 2005-06 to 2015-16, growing at an average annual rate of 5.3%, higher than the average in Sub-Saharan Africa. This growth translated into gains in the fight to reduce poverty, with about 4.5 million Kenyans escaping poverty. Poverty measured under the national poverty line declined from 46.8% to 36.1% of the population. However, a closer look shows that not every segment of the population benefited from this impressive growth.

First, the good news. Poverty declined considerably in rural areas, from about 50% in 2005-06 to 38.8% in 2015-16, largely accounting for the reduction at the national level. This was possible because of the increasing importance of non-agricultural income (particularly commerce) to supplement agricultural income for rural households, which has been aided by the expansion of mobile money and the telecommunication revolution.

Annual GDP growth rates, 2007-2016

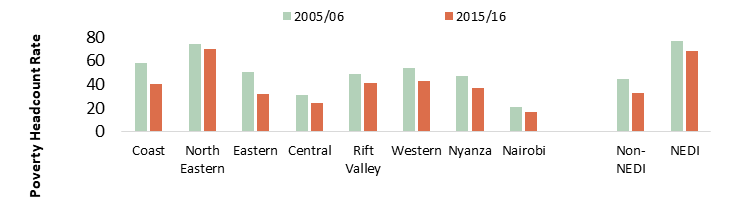

Poverty headcount rate measured at the national poverty line

Urban areas did not fare so well. The urban poverty rate remained statistically unchanged, and in fact, the absolute number of urban poor increased from 2.3 million to 3.8 million due to high population growth. Increasing living costs, especially because of high housing costs as well as high food prices, paired with scarce job opportunities have reduced the disposable income for urban households. It seems that in Kenya, cities—and especially the informal settlements within them—are not reaping the benefits of access to jobs and services. For example, a worker in Nairobi can only reach 25% of existing jobs within 60 minutes using the mini-bus system, while in Dakar, Senegal, they can reach 52% of existing jobs.

Even at the county level, reduction in poverty has been disparate. The North- and North-Eastern counties (commonly referred to as NEDI counties) are suffering from high and stagnating poverty rates, at around 68% in 2015-16, and they require a multisectoral effort to raise the living standards. For this part of the country, lack of proper access to basic services can have long-term consequences, particularly in building human capital, if nothing is done. Educational enrollment rates are far below the national average, especially at the secondary level. Health care access and utilization indicators are also very low compared to the rest of Kenya. Vaccination rates in some NEDI counties reach only about 40% compared to more than 90% in the Central province. Limited access to health care coupled with extremely high fertility rates results in the highest maternal mortality rates of the country. A child in NEDI counties is likely to be born poor and remain in poverty, without being able to develop their productive potential.

If Kenya continues on its current growth path, poverty will remain above 20% by 2030. The main challenge is not so much to raise the growth rate but rather to ensure that the benefits of economic growth reach all segments of the population. The Kenya Poverty and Gender Assessment provides an in-depth analysis of the evolution and nature of poverty and identifies several policy areas that can help accelerate poverty reduction in the coming years.

To further reduce rural poverty, it will be crucial to improve agricultural productivity, through high-quality extension services to help farmers apply best practices and better access to inputs. More and better job opportunities—especially for youth—are important for rural areas and particularly crucial for cities. This requires infrastructure investments to improve transportation and service delivery, and more affordable housing. In addition, targeted and multisectoral interventions are needed to raise the living standards of marginalized segments of the population such as the NEDI counties. Last, but not least, social safety nets can play a crucial role in protecting the most vulnerable, and building the human capital required to raise Kenya’s productivity.

With robust growth over the last decade, Kenya is at the pole position to make remarkable progress in poverty reduction. In addition to sustaining growth, it will require specific policies to translate growth into poverty reduction so that 2030 will be a year with a considerably lower poverty rate than the projected 20%.

Join the Conversation