Significant gender gaps in labor market outcomes in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) hinder the country’s efforts to achieve inclusive economic growth. Only 62% of women in the DRC participate in the labor market and a mere 6.4% of women work in wage employment, compared to 23.9% of men. Our new joint GIL-SSI report is the most comprehensive investigation to date of the reasons why—and provides insights on what can be done about it. We combined two nationally representative datasets, the Demographic and Health Survey and the 123 Survey, with four impact evaluation datasets collected by the Africa Gender Innovation Lab to look at gender differences in economic outcomes across the country.

How large are the gender gaps?

As illustrated in Figure 1, we found that women are 8.2% less likely to work than men. Within agriculture (the largest economic sector in the DRC) female farmers produce 17.8% less—and 10.9% less per hectare—than male farmers. Moreover, women have 77.3% lower wage earnings than men, and 66.5% lower business profits than male entrepreneurs.

What are the factors behind these gender gaps?

To investigate the reasons behind these inequalities in outcomes, we conducted a statistical decomposition analysis. We found that women’s lower access to key productive assets and lower economic returns from getting married are consistent factors driving the gender gaps in Figure 1. But across economic sectors, there are also differences in what matters.

- The number of dependents, capturing women’s higher burden of care work, is the primary factor behind women’s lower labor force participation.

- Women’s lower agricultural yields are mainly driven by their concentration in food crops versus higher-value cash crops (such as palm oil, coffee or rubber).

- A lower number of workers hired in female-led enterprises emerges as the single most consistent driver of the gender gap in business profits, though businesswomen’s lower levels of capital compared to their male counterparts also matter.

- Lower educational attainment, skills and concentration in lower-paying sectors are the primary drivers of women’s lower wage earnings.

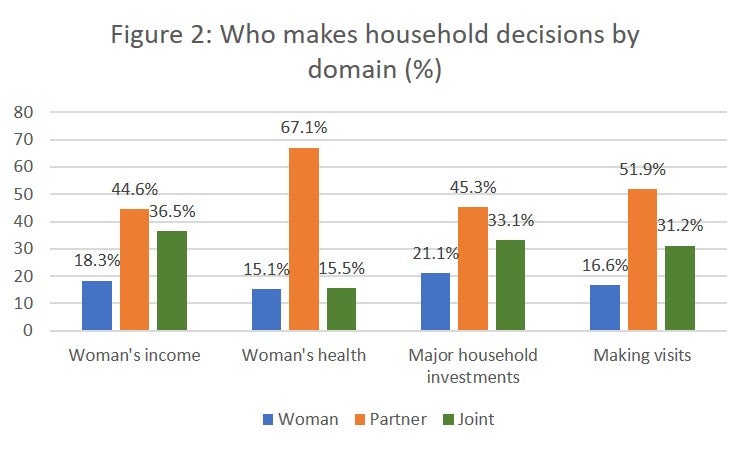

Beyond these economic factors, women’s limited power in households and communities is another important reason underlying the gender differences observed in Figure 1. For example, women often have limited control over household decisions (Figure 2). This lack of agency has a profound effect on women’s economic empowerment by dampening their productive incentives and influencing what they can do with their time.

To dig deeper into how limits on women’s agency affect their economic success, we conducted a qualitative research study among entrepreneurs in Goma. Our interviews showed how women are consistently less empowered than men to make decisions affecting their lives. Women also face particular vulnerability to shocks, which range from physical to financial to institutional insecurity.

Our interviews also highlighted examples of men using their wives’ profits without their consent, preventing women from reinvesting in their businesses or increasing their savings. Even if a woman has an income generating activity that is successful, she may not be able to grow it or even continue it. This is illustrated by this quote from a cross-border trader:

“There are some women who are helped by their husbands, even if this category represents only 20 percent. The other 80 percent [of husbands] are rather there to cause their wife’s business to fail. These are the husbands who steal their wives’ money, whose only job is to thunder around the house to demonstrate their power as household head.” -- Women cross-border traders focus group, Goma

As a result, we found instances of women resorting to storing money secretly outside of their homes for fear that their husbands would steal from them or interfere in their business. Whether giving to friends or family in secret, or keeping their money on their person, these practices are highly risky and leave women with little recourse when their savings or investments are lost or stolen.

What can we do about it?

To address these challenges, our report presents a series of evidence-based policy recommendations to increase women’s agricultural productivity, educational attainment and skills, access to capital, physical security and agency.

There are clear opportunities to incorporate these policy priorities into programming, including for example in the multi-sectoral Jobs and Economic Transformation (JET) agenda. To increase women’s educational attainment and skills, interventions could provide adolescent girls with life skills and livelihoods training, which increase the likelihood of participants engaging in income generating activities, staying in school, and having increased savings and control of their money. Options for improving women’s access to capital include facilitating secure savings mechanisms and providing cash and productive asset transfers. To close economic gender gaps, projects should consider providing childcare and implementing gender transformative interventions engaging men, which have been shown to increase men’s contribution to household responsibilities. Our report’s Evidence Review has more background on these ideas and contains many other innovative policy options.

Lastly, our work highlights areas where there is a need for more rigorous testing—and comparison—of interventions that address key issues such as improving women’s access to land and supporting women’s adoption of cash crops. More high-quality data collection and research will be critical to move the needle for women’s economic empowerment in the DRC.

Join the Conversation