Realizing Nigeria’s economic potential requires a stronger focus on women farmers

Realizing Nigeria’s economic potential requires a stronger focus on women farmers

Unequal public investment in women and men is perpetuating gender inequality in Nigeria, which continues to take a toll on both Nigerian society and the economy. In the agriculture sector alone, forgone earnings from gender gaps in productivity are estimated to amount to at least $2.3 billion annually and more when accounting for spillovers to other sectors (World Bank 2022). To realize the gains from women’s full participation in agriculture, the Government of Nigeria is working to adopt a gender-equitable approach to budgeting and create the needed fiscal space to address gender gaps in the sector.

As part of a recent public finance review led by the World Bank’s Macroeconomics, Trade and Investment team, the Nigeria Gender Innovation Lab conducted a diagnostic analysis to assess the gender-incidence of public spending in the agriculture sector in Nigeria. Using plot-level survey data from the 2018–19 wave of the Nigeria General Household Survey (GHS) and budget data provided by the Government of Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMARD) and the Budget Office of the Federation, the team analyzed the gender dimensions of participation, input distribution, and budget allocation across various crop value chains supported by FMARD.

Several key findings emerge that offer guidance on priority areas for consideration in the budget process:

1) Public investments that promote the use of agricultural inputs and mechanization are not reaching value chains where women are concentrated.

Analysis of the budget data revealed that the top four value chains that received the highest levels of investment, i.e., cotton, rice, sorghum, and cocoa, were among those with the lowest female farmer participation, with gender gaps in participation—measured as proportion of plots managed by women versus men cultivating specified crops—ranging from 64 percentage points to 88 percentage points (Figure 1). In 2020, for instance, three of the four value chains with the largest budget allocations (400–600 million naira) were the value chains with the largest gender gaps in participation and yield: rice, acha, and millet/sorghum.

Figure 1. Budget Allocation and Women’s Agricultural Participation

Moreover, the majority of inputs in most value chains is allocated to male farmers, as they constitute the majority of farmers in all value chains. Meanwhile, the allocation of irrigation, mechanization, and tools to women is roughly 35 percent (relative to the 65 percent allocated to men), regardless of women’s level of participation in value chains. The underinvestment in inputs and mechanization for women farmers is holding them back on two fronts. First, it prevents women from accessing the support they need to expand productivity within the value chains where they are already concentrated. Second, it poses additional barriers to women farmers who wish to adopt more lucrative, male-dominated crops, but who lack access to inputs, mechanization, and other resources, ultimately disincentivizing them from crossing into these chains.

2) Women farmers need more support to increase their use of extension services, expand their access to markets, and encourage their transition to higher-value crop value chains.

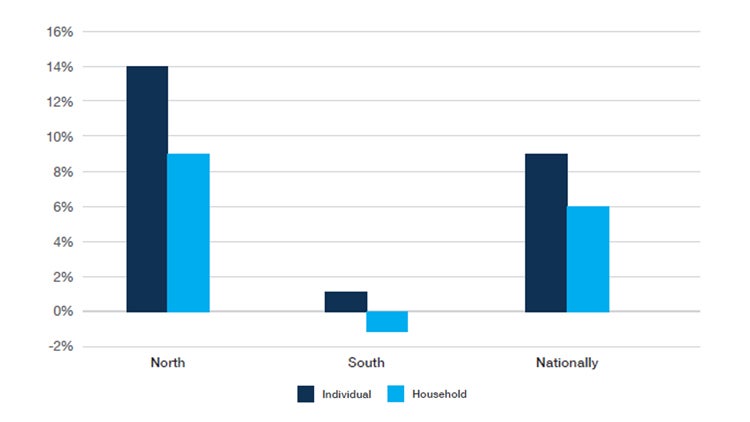

While overall participation in extension services is low in Nigeria, there is a 9-percentage point gender gap in direct participation in extension services, driven by women’s low participation rates in the North. Women are disadvantaged in their ability to benefit from extension services directly (as individuals) or indirectly through their households in the North, although in the South, women are more likely to access extension services through their households (Figure 2). Women’s direct participation in and benefit from extension services could be improved through increased and targeted funding for crop value chains in which women are engaged (as opposed to the current general budgetary prioritization of predominately male value chains).

Figure 2. Gender gaps in participation in extension services

Note: The gender gap in individual participation in extension services is the difference between the share of male and female plot managers who directly participated in extension services. The gender gap in household participation in extension services is the difference between the share of male and female plot managers who report someone in their house participating in extension services.

Furthermore, women farmers face considerable barriers to accessing financial services, which restricts their ability to reach markets at various stages of the agricultural cycle. To help women access markets and overcome barriers to entry into more profitable value chains, public funding needs to be targeted toward supporting or subsidizing innovative financial mechanisms. Targeted financing for training modules on personal initiative and socioemotional skills for women could also be added to extension training and has been shown to increase women’s likelihood of adopting more valuable crops.

3) More gender-disaggregated data would unlock better analysis of spending inefficiencies.

While this expenditure analysis reveals important insights into the gender-incidence of public spending, to undertake a more complete analysis and facilitate evidence-based policymaking, more investments need to be made in recording gender-disaggregated data. Critically, the continued collection and monitoring of such data can provide evidence on differences in budget allocation and how spending can impact agricultural productivity, and in turn guide future budget and spending decisions to close key gender gaps in agriculture in Nigeria.

The authors thank Ayodele Fashogbon, Laurel Morrison, and Julia Vaillant for their valuable contributions.

Join the Conversation