Seasonal deprivation in the Sahel is large, widespread, but it can be anticipated and addressed

Seasonal deprivation in the Sahel is large, widespread, but it can be anticipated and addressed

In April 20202, Action Against Hunger published a report presenting a set of measures designed to mitigate the impacts of the upcoming food crisis. The report started with a statement that is likely to evoke a strong sense of déjà-vu for any development practitioner familiar with the Sahel : “The 2022 lean season is likely to be particularly difficult for food and nutrition security in the Sahel”.

The lean season, which coincides with the rainy season, is the period when stocks are depleted, and food prices reach their peaks. Even though the lean season threatens Sahelian households every year, several important questions remain. What is the true impact of the lean season on household welfare? Is seasonality a shock or a well-known and well-managed characteristic of Sahelian life that households can anticipate and deal with? Are seasonal transfers the best instrument to mitigate the impact of seasonality?

Drawing on the detailed analysis from a new brief, Anticipating Large and Widespread Seasonal Deprivation in the Sahel, based on survey data from the "Enquête Harmonisée sur les Conditions de Vie des Ménages” (EHCVM) collected across five Sahelian countries during the 2018 harvest period and the 2019 lean season, we provide some answers to these questions.

Seasonality leads to decreased consumption and increased poverty

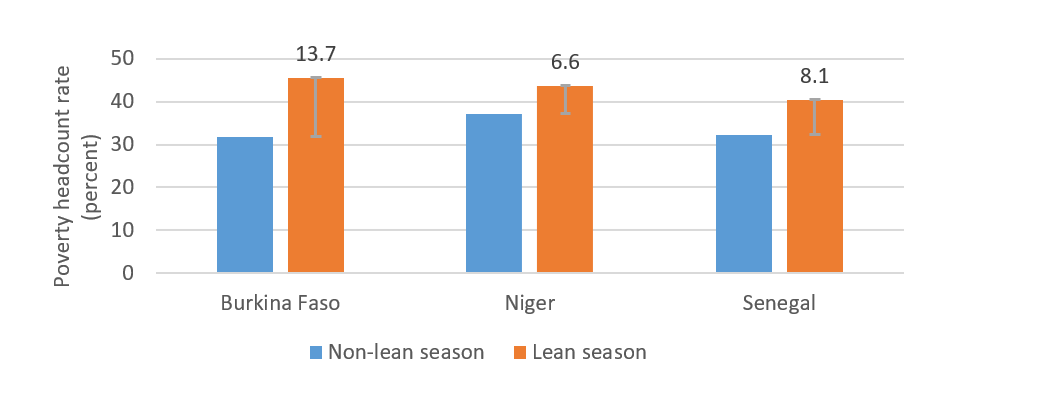

Sahelian households experience large seasonal swings in monetary welfare and poverty, even in the absence of climate shocks. Even though the 2018 rainy season was considered “above average” across the Sahel in terms of the timing and reliability of rainfall, household consumption was significantly lower in the lean season, highlighting the importance of seasonality even when the agricultural season is good. Pooling the data from Burkina Faso, Niger, and Senegal, mean real monetary consumption was 9.5 % lower in the lean season than in the non-lean season. This is enough to push vulnerable households below the poverty line. The share of the population living below the national poverty line in the lean season was 13.7 percentage points higher in Burkina Faso, 6.6 percentage points higher in Niger, and 8.1 percentage points higher in Senegal compared to the non-lean season (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Difference in share of the population living below the national poverty line between the lean season and non-lean season waves

Note: Consumption deflated and adjusted for comparison with national poverty line in each country. Seasonal differences are statistically significant at the 5 % level in a linear probability model, which includes controls for household characteristics and region fixed effects. Source: EHCVM and World Bank estimates.

Seasonality puts households at risk of food insecurity

Food insecurity and malnutrition increase in the lean season, which is consistent with more extreme forms of deprivation. Seasonality has a greater impact on food consumption than non-food consumption, which may be less sensitive to seasonal swings. Moreover, while we did not observe a decline in dietary diversity between the lean and non-lean seasons, both expenditure and quantities consumed of staple foods dropped. Instead of cutting consumption of more expensive or nutritious food, households reduced the consumption of the most fundamental food items in their consumption basket, with potentially dire consequences for their food and nutrition security during the lean season.

The effects of seasonality can be felt before the beginning of the lean season, highlighting the need for early action

The effects of seasonality can be felt as early as April and increase as the year – and the agricultural lean season – draws on. Since the interviews in the EHCVM data largely took place between April 2019 and July 2019, but the agricultural lean season continues well into September, this means that seasonality has even larger effects than our analysis suggests and that the typical lean season assistance provided between June and September arrives too late to protect households from deprivation.

Improving preparedness and early-warning, early-action mechanisms is a growing area of interest in the Sahel. In Niger, the government has developed a trigger-based adaptive safety net program for drought response that was activated in November 2021 when the trigger threshold was reached in several communes reflecting the poor performance of the 2021 rainy season. Providing early action to address the adverse effects of seasonality does not require a sophisticated early warning system. By its very nature, seasonality poses a chronic threat that can be anticipated. Existing social protection systems can provide timely assistance to households impacted by seasonality by expanding coverage of regular safety net programs and triggering seasonal response programs as early as February or March.

Livelihood diversification is key to reducing the vulnerability of rural households

Risk coping strategies are limited in the Sahel. Households rely primarily on agriculture, and their income sources are not well diversified, especially in rural areas. Rural households are especially vulnerable to the effects of seasonality and within rural areas, seasonal swings in welfare are concentrated in the large share of households that cultivate crops; households avoiding agriculture entirely do not experience the same seasonal shifts in consumption. Although households where the main income earners worked outside of agriculture were not fully protected against the impact of seasonality as they often had secondary activities linked to agriculture, interventions that promote diversification of income generating activities have the potential to reduce their exposure and vulnerability to seasonality and to shocks and to build their resilience.

Join the Conversation