Imagine 20-year-old Aman, who did not finish secondary school, struggling to get by in the unforgiving Ethiopian urban labor market: even a bad job seems hard to come by. Aman feels as though he has no control over his economic prospects. Without adequate psychological resources to restore his sense of self-integrity, it is easy to slip into negative thought cycles and give up. What Aman is going thru is what many young people in Ethiopia are facing and will continue to face in the next few years, given the devastating effects of COVID-19 (coronavirus) on the country’s labor market.

In an effort to explore whether there is a cost-effective way to help people navigate the psychological terrain of job-search, in 2018 we conducted an RCT (randomized control trial) in Addis Ababa. The aim was to test if behaviorally informed interventions aimed at increasing self-integrity and promoting goal-orientation, have positive effects on job search and employment in the short-term. For this, we partnered with local experts to organize two workshops for Ethiopian vulnerable youths living in the poorest neighborhoods of the city. We invited 1,800 young men and women to participate in the study, and randomly allocated them to either the self-affirmation workshop or the self-affirmation + goal-setting workshop, or to a control group.

The self-affirmation workshop focused on exercises designed to promote participants’ sense of self-integrity through self-affirmation exercises by reflecting on one’s core personal values, and how meaningful these values are. The self-affirmation + goal-setting workshop, included activities that encouraged participants to reflect on their goals and set plans as to overcome the obstacles to achieve their goals, in addition to the self-affirmation material.

We tracked participants for about four months after the intervention, collecting information on their job-search intensity and the amount they were working and earning, as well as two psychological variables: locus of control and conscientiousness. Locus of control measures the amount of agency a person believes they have, while conscientiousness captures the diligence with which a person undertakes their tasks.

Two main results from our study stand out.

First, the workshops increase both job-search and employment for men, but not for women. There are no statistically significant effects of the intervention for women, but it increases job search and work for men. The impact on men is largely driven by the self-affirmation workshop and on the intensive margin (e.g., men who are already searching, do it more intensely). Men invited to the self-affirmation workshop spend on average about 10% more time searching for work compared to the control group, and about 24% more hours working (Figure 1).

Figure 1. ITT effects of self-affirmation workshop on men

This gender gap can be explained by the radically different constraints that female and male participants report when job-searching. At baseline (before the intervention), almost 1 in 2 women report that they are not searching for work because they are fulfilling family responsibilities. Less than 1 in 5 men see this as a reason. Men were far more likely than women to attribute the fact that they were not searching due to lost hope and motivation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Main constraints when looking for a job for males and females (at baseline)

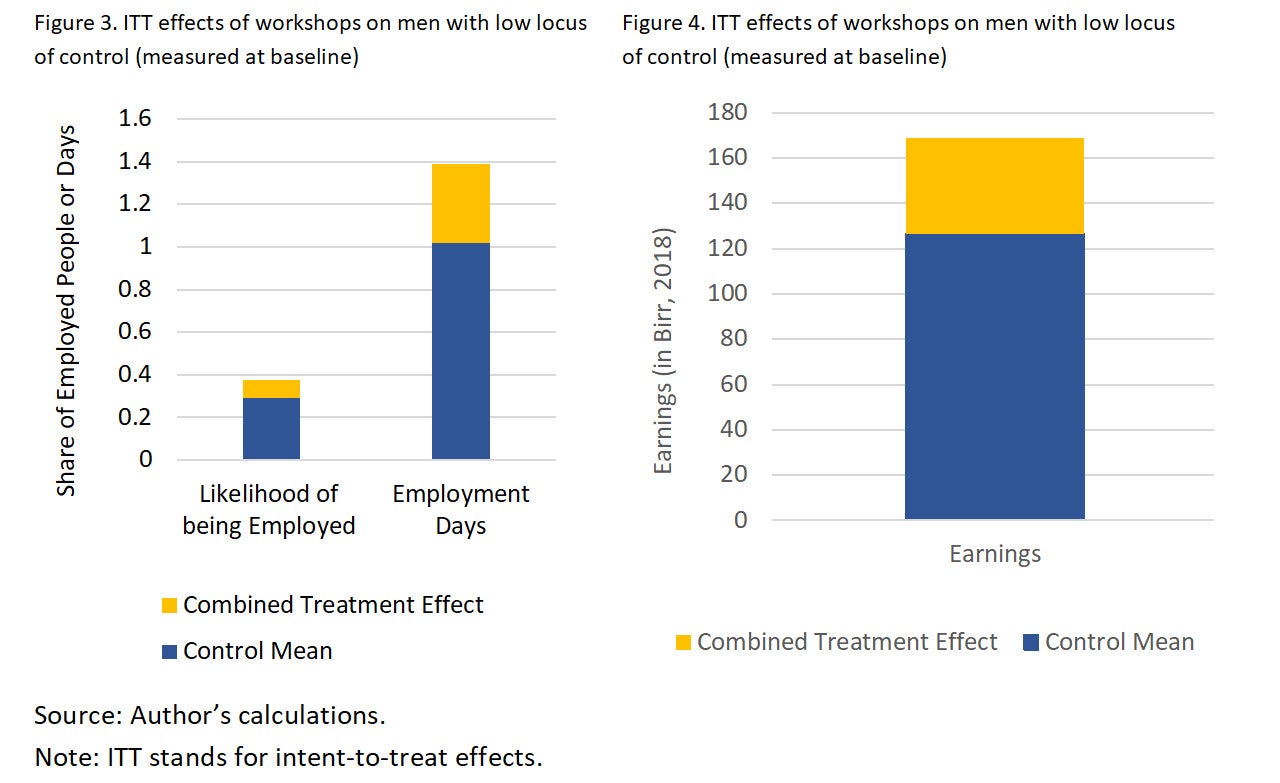

Second, the workshops are strikingly effective for men who entered the study with low psychological agency (locus of control). For this sub-group, being invited to either workshop increases the likelihood of being employed by almost 30%, the days worked by around 36% and earnings by 33% (Figures 3 and 4). Not surprisingly, for these men we also observe major improvements in their locus of control measure.

Effects of providing psychological tools to youth in Addis Ababa (RCT conducted in 2018)

We see four main lessons coming out from this study:

- Well-targeted psychologically informed interventions can be a highly cost-effective complement to conventional labor market interventions, such as vocational training

- To design inclusive labor markets, policymakers must address the gendered asymmetry in the allocation of household responsibilities: housework and caregiving (for children and others). Solutions may include support for the provision of reliable and affordable childcare (vouchers, establishment of centers). It could also be socio-cultural, by addressing gendered expectations and social norms in the longer term.

- Implementation matters. Counter to our expectations, the self-affirmation workshop had effects that the combined intervention (self-affirmation + goal setting) did not. Too much material in a limited timeframe or emphasizing more than one psychological construct at a time may be counterproductive for participants.

- Local expertise matters when employing behavioral science. Interventions designed to address subtle aspects of mental life are highly sensitive to context. We doubt such promising results could ever be obtained without working closely with local implementors.

Join the Conversation