Tanzania has shown massive achievements in education – well known progress in primary enrolment plus less well known, but in some ways even more spectacular, growth in post-primary education.

Yet, Tanzania needs to improve learning outcomes if a virtuous cycle of growth and human capital investment is to be sustained. This is “The Steep Learning Curve” which Tanzania needs to get onto with modest fiscal resources but a rapidly growing number of new students, and therefore with a keen eye for value. This should be possible.

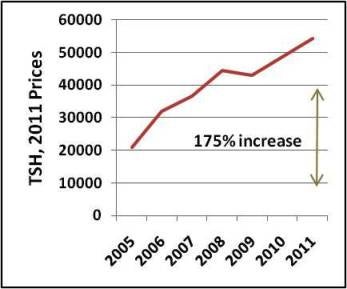

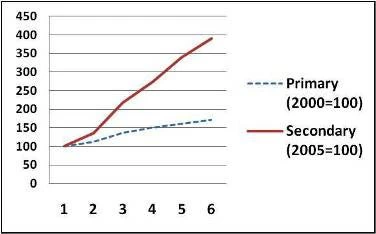

In the last decade, strong growth, plus expanding aid inflows, allowed Tanzania to finance a massive expansion in the public schooling system. About 20 percent of public expenditures were invested in human capital through the public education program. Primary school student enrolments increased first by 72 percent, followed more recently by an astonishing 290 percent increase in secondary school enrolment (from a very low base since below 10 percent of youth were attending in 2005).

Figure 1: Education Expenditure per capita

Figure 2: Expansion in student enrollments

The primary expansion was achieved initially without a decline in quality – but quality was already low, and has been falling again since 2007. Primary School Leaving Exam (PSLE) results have fallen back from the peak in 2007, when the pass rate hit 70 percent, and are now about 55 percent. Low quality threatens the returns to investment in primary education and could undermine the success of the post-primary expansion.

In secondary education, the decline in quality could be described as a crisis. Pass rates fell below 10 percent in 2010 – there were fewer passers then than in 2007 whilst student numbers have rocketed. A drop off in average quality is to be expected, with a lag, following a big expansion, but this level of outcomes has become a source of major concern.

Looking forward, education service improvements will need to come from better value for money in public spending. All projections indicate that public money will be insufficient to keep pace with the growth in students expected to enter the entire school system every year –as much as 30 percent per year in secondary schools (and universities) during the next decade.

Fortunately there is plenty of room to improve value for money of the overall education system in Tanzania. The solutions, however, differ between primary and secondary education. In primary, the overall envelop of resources might be adequate but huge variations in performance across districts and schools offer opportunities for improving the allocative efficiency of resources. In secondary, the performance is weak across the board since the average student fails the Form 4 exam in 96 percent of schools. The solution is not a question of reallocating resources, but to adjust their level to the number of students and find more qualified teachers.

In primary education, the authorities could achieve efficiency gains by:

Optimizing the geographical allocation of resources: Tanzania’s system persistently allocates resources to the districts and schools where they are already concentrated. Resources explain results – and there are decreasing returns to scale, so there are major efficiency gains (25 percent) to be had by creating a more equal distribution of resources. The Tanzania Economic Update has details on possible solutions.

Taking action in particular low-performing districts or schools: Some schools and districts persistently underperform – getting results of a third or a half of what might be expected given resources and social conditions. Tanzania’s system doesn’t do much about this but the wastage is significant, up to another 25% improvement in efficiency is possible. Tanzania economic Update provides concrete recommendations on how to achievement those gains.

These two actions have already been recognized by the Tanzanian authorities but their implementation has been rather slow. Not only responsibility for performance is diffused across many parts of Tanzania’s system but the proposed reallocation of resources would also generate winners and losers among districts. A well-known finding of the political economy literature is that losers might block the process and help preserve the status quo.

Actions in secondary education are even more urgent and measures must aim at increasing the resources per student whilst maintaining or improving cost effectiveness. The steep decline in pass rates at the secondary level is linked to the fast expansion of students; much faster than resources, so spending per student fell by 57 percent between 2005 and-2008. Government, with the support of donors, has started to direct more of the education budget to secondary but there are other constraints. For example, a recent survey showed that 72 percent of existing secondary teachers couldn’t speak English at the level needed to teach their courses (English is the language of instruction at secondary schools). It’s not clear that more resources can hire more teachers if well qualified people are not available locally.

Measures to increase the intensity and effectiveness of resources available per student could include:

- Mobilizing/permitting complimentary contributions from the private sector, including from parents;

- Consider greater use of private provision of publicly funded/subsidized places;

- Target extra help on students based on need, e.g. through vouchers or Conditional Cash Transfers as already experienced in some parts of the country;

- Target help on struggling schools before more schools are opened, as in the World Bank’s secondary education development program (SEDP);

- Reconsider the target level for the secondary student population.

For Tanzania, the learning curve is steep but stakes are high. In the future, the Government will have to provide better education quality to a growing number of students, especially in secondary schools, without necessarily much more financial resources. Failing to take action will mean that quality will be sacrificed. Huge enrolment growth is a great achievement but the measure of success now has to shift to the number of students graduating with useful learning (as measured by examination success). It is what students get from schools in terms of learning outcomes that will ultimately contribute to the country’s human capital stock and pave the way to further productivity gains and jobs.

Join the Conversation