This train could be Kenya in East Africa’s race to Middle Income. The country remains the richest in East Africa and with almost US$800 income per capita is the closest to meeting the international Middle Income threshold of US$1000. But its EAC partners Rwanda, Uganda and Tanzania are catching up fast.

Kenya could be the first EAC country to reach Middle Income status by 2020, but only if it achieves its potential of about 6 percent uninterrupted economic growth. However, if Kenya’s economy only grows at 3.7 percent (the average of the last decade), the train will likely be overtaken by Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda in the next ten years. Middle income status would still be possible, but only by 2037.

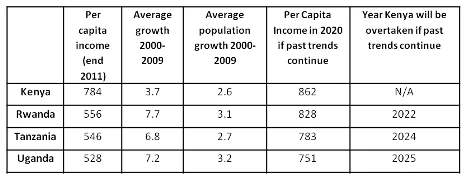

Today, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda have per-capita incomes of around US$ 550, substantially below Kenya’s. If past trends continue, Kenya would still be ahead in 2020 but the gap would gradually narrow (see table) and by 2022, Rwanda would take first place soon followed by Tanzania and Uganda.

Table: East Africa’s ride to Middle Income

Source: World Bank estimates and projections

The fact that most of East Africa can reach Middle Income in the next ten years is remarkable and more important than the ultimate ranking of the frontrunners.

Today, the EAC is one of the fastest growing regions in the world. If Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda maintain their ongoing growth momentum and if Kenya accelerates, all four countries will reach Middle Income status within the next ten years. For the first time since independence, sustainable development appears possible for East Africa, even for countries that started off from very difficult positions.

Last week I was in Rwanda, a country that has achieved according to Paul Collier, what no other country in Africa has achieved in recent times: the “hat-trick” of high growth, significant poverty reduction and reduced inequality.

Making it to the Middle Income station is not the end of the journey. Most economic challenges will remain, including fighting poverty. At an annual income of US$ 1000 the average East African would only “earn” US$ 83 per month, or less than US$3 per day. However, being a middle income country brings you into a new league of countries, and the right to be compared with the so−called “emerging economies”.

Global players have also taken note. No week goes by without a major international company announcing plans to expand its East African operations or to relocate there, often in Nairobi.

Regional integration is one way for the Kenyan train to reach the station sooner. Larger markets allow companies to reap economies of scale, produce a larger set of goods in greater quantities and thus increase variety and reduce cost for consumers. Already today, Kenyan firms are investing in Tanzania, Uganda and Rwanda, and these countries benefit from cheaper, higher quality products.

Much more could be done. Agriculture and transport are two areas where reforms are badly needed to improve intra-regional trade. East Africa could easily feed itself simply by allowing markets to work. While Kenya has a structural food deficit, Tanzania and Uganda typically have surpluses of basic food commodities. If these three countries traded with each other more effectively, Kenyans would pay less for food, especially maize, while Tanzanian and Ugandan farmers would earn more. Priority should be given to regional roads and corridors, as today it is costly, sometimes impossible, to move goods across the region.

The port of Mombasa is the gateway for most of East Africa’s products. Unfortunately, it is one of the worst performing ports in the world, and its closest competitor–the port of Dar es Salaam–is achieving even less. Today, Mombasa transacts in one year what Singapore handles in a week. A better functioning port would increase the flow of goods, reduce costs and attract industries, many of which are looking for a new home, as Asia is becoming more expensive. It would also favor the flow of goods transiting to and from landlocked countries (Rwanda and Uganda) and operate as a catalyst for the region.

Infrastructure which connects people and markets will be critical for East Africa to become one the world’s new emerging regions. One huge challenge remains the railways. The day when Kenyans will board a train to Kampala with perfect confidence that they will reach their destination comfortably, reliably and fast, is the day you will know that the region is firmly on the Middle Income track.

Join the Conversation