Today, many would challenge his perspective. Obesity is a massive problem in rich societies and rapidly becoming one in emerging economies too. As a result, heart disease and diabetes are also on the rise.

But for me, sport means so much more than just personal fitness. I practiced Judo competitively as a child, which helped me to stay focused, taught me important life skills –especially teamwork— and formed friendships that have lasted until this day. My passion for sport has been reenergized in Kenya, where you can be outdoors all day long and all year round… much better than sitting in front of the TV (football games excepted).

But at the macro level, is sport also contributing to national development? Does it help or hurt in building a nation and growing an economy?

Sport has a major symbolic value and shapes national self-perceptions. Sport, especially football, can unite countries. Germany’s victory at the World Cup in 1954 was associated with its economic re-birth and seen as a sign of national re-emergence: after the self-inflicted trauma of WWII, Germans could finally be proud of themselves again. Interestingly, the last time ”we” won the World Cup was in 1990, the year of German reunification.

Kenya’s runners, much like Germany’s footballers, have become the nation’s flag-bearers. They have made this country visible on the global stage and inspired a new generation of athletes.

At the London Olympics, Kenyans won eleven medals, two of them gold. Although more were expected, still Kenya remains the global powerhouse in running. Kenyan athletes are even starting to enter new areas in track and field (see Julius Yego’s remarkable performance in the Javelin). Many other countries can only dream of achieving Kenya’s Olympic performance. At the same time, Kenya is underperforming in many other sports, especially in the nation’s other favorite: football. Why such difference?

The most popular explanations for Kenya’s supremacy in running stress altitude, physical aptitude, and monetary incentives. Perhaps these are important, but they ought to apply to football as well. In the absence of solid research on the topic, let me propose three hypotheses, which also tie-in with social and economic development:

First, getting started in running is relatively straightforward and, more importantly, the start-up costs are minimal. To run, all you really need is a good pair of shoes: in fact many future stars even started-off barefoot when they were children. In football, you don’t need much to get started either (which helps to explain why developing countries are advancing much faster than in, say, fencing) but significantly more than for running: a ball, a pitch and fellow team members (which means you may need to commute if you live in a remote area). The best training for distance running is piling up mile after mile; for football top performance requires intensive skills-based drills delivered by qualified coaches from a young age. Football also requires continuous competitions to challenge players and teams, and football leagues are more difficult to set-up than road races. In football, raw athletic talent – which Kenya has an abundance of – will only get you so far if it isn’t converted into specialized skills through specialist coaching and management.

Second, success breeds success. Kenya’s top runners earn a very good living providing them, unlike some other folks back home, with a secure financial future. They are adored in their communities and a source of inspiration for the next generation. For many children, running seems like their best shot at moving out of poverty. In other words, successful role models who have succeeded at the highest level will help inspire other Kenyans to succeed – we need more examples like McDonald Mariga who was part of the Inter Milan squad when they won the Champions’ League in 2010.

Third, the middlemen and support structures are less important in running. Team sports demand a more complex organization and the governance environment matters more (not exactly an area of Kenyan strength). For instance, coaches may have some discretion and influence over the composition of running teams, but they just can’t impose a blatantly slow runner. In football, we’ve seen players go as far as paying the coach or federation to be allowed on the team. You can imagine what this does to team morale and performance. In addition, successful football nations invest heavily in intensive coaching for their young players, relying on football associations to effectively coordinate the training of several thousand coaches. This sort of complex coordination requires good governance. It is no coincidence that Africa’s best performing team at the last World Cup was Ghana, a country which has some of the highest scores in Africa on world governance indicators.

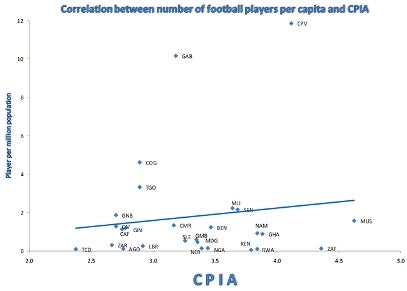

To Kenyan football fans, all hope isn’t lost. World Bank Africa Chief Economist Shanta Devarajan and Economic Director Marcelo Giugale have carried out some fascinating analysis, identifying a strong relationship between the quality of a country’s policies and the performance of its footballers (see figure).

Source: Shanta Devarajan, CPIA launch, Nairobi 2012

The good news is that Kenya’s policies have been improving in recent years, so football results should hopefully follow suit. This is because, with better policies, countries develop economically; better institutions are set up and a more vocal civil society demands good governance and accountability for all aspects of life, including sport. At least, that’s the theory. In practice, as Sepp Herberger (Germany’s legendary coach of the 1954 squad) put it: “The truth is always on the pitch”.

Join the Conversation