How would you feel if, after a normal take-off, you noticed one of the engines on your plane wasn’t working properly? What if you then found out the other engine was overheating? Now suppose the captain announces that you should buckle-up because the plane is about to meet an approaching hurricane?

This is what Kenya’s economy is currently going through. The country is in the middle of a perfect storm, and the declining Shilling is the most visible manifestation of Kenya’s economic woes. Why has the Shilling been falling so much and so unpredictably?

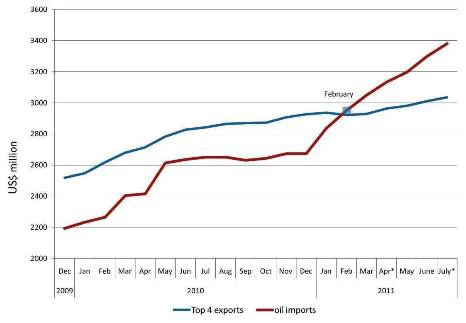

The main reason is that Kenya’s economy is increasingly imbalanced: the country is importing too much and exporting too little. This makes it vulnerable to shocks. The gap between imports and exports needs to be financed by financial inflows other than export earnings. In 2011, imports have soared (mainly due to higher oil and food costs), while exports remained stagnant. The gap between imports and exports, also called current account deficit, now stands at above 10% of GDP – one of the highest in the world! Today, Kenya’s main exports don’t even earn enough to pay for its oil imports, not to mention other imports beyond oil (figure)! The money to pay for any additional imports needs to come from somewhere.

Figure – Since February 2011, Kenya’s top exports can’t pay anymore for its oil imports (click on figure to see it larger)

Source: Simulations by Jane Kiringai and John Randa, Kenya PREM; Data points reflect 12 months moving averages

The money won’t come from manufacturing exports: that is Kenya’s weak engine. Manufacturing stagnated a long time ago in Kenya, though it has been the driving force of other successful emerging economies. Ten years ago, manufacturing accounted for 11 percent of Kenya’s economy–and it is the same today, despite a decline in the share of agriculture from 30 percent to 25 percent. Kenya’s growth has been in services, particularly transport and telecommunications, reflecting the resurgence of Kenya Airways and Kenya’s telecom revolution.

If you import a lot, you need enough dollars to pay for these imports. Ideally, exports will give you everything you need. When exports aren’t enough—which is the situation in Kenya today-- the gap needs to be filled through other financial inflows, including remittances, private investment, and support from development partners. In Kenya, over the last six months, the share of short-term flows has increased substantially. This “footloose capital” makes Kenya even more vulnerable to shocks. It often just takes a single event – even if it is completely unrelated to Kenya – to prompt these short-term flows to leave the country as quickly as they came in. This is Kenya’s overheating engine.

A weakening Shilling is not necessarily bad for Kenya’s economy. It can help to rebalance Kenya’s economy in the medium term, by making imports more expensive and exports more competitive in the countries where those exports are bought, thus adding to export earnings. Unfortunately, in Kenya, high inflation has been eating away some of the benefits that it would get from a weaker exchange rate, thus creating additional pressure on the Shilling. If investors, local and international, think their money will lose its value in Kenya very quickly – which happens when inflation is high – they tend to move it to countries where it will hold its value over the medium-term. If policy makers are not careful, Kenya could well end-up in a vicious cycle where high food and fuel prices lead to higher inflation, which in turn weakens the exchange rate, which raises the cost of imports, which further increases inflation. This would be a bad outcome for Kenya. Even if international food and fuel prices decline – which they did since August – inflation can still go up: indeed, it reached a new peak at 17.3 percent in September.

The economic storm which was already brewing in the first half of 2011 has now reached full force and has accentuated Kenya’s structural weaknesses. The turbulence in Egypt meant fewer tea exports to one of Kenya’s main markets. The subsequent struggle in Libya increased global oil prices and the import bill. Now, the next storm is approaching and it could become a hurricane, not just for Kenya: the Euro crisis and the apparent helplessness of European policy makers to deal with it, is having repercussions across the world, including Africa. Two of Kenya’s key exports and foreign exchange earners, tourism and horticulture, still depend largely on European markets. Flowers and vacations are luxury goods, and are among the first purchases that Europeans will cut-off if they go into a full-fledged economic crisis.

What should the pilot do if one engine is failing, the other one is overheating, with the plane tilting, and a hurricane is approaching? Here’s what not to do: adopting strategies that have demonstrably not worked in the past, such as adopting price controls or establishing parallel currency markets, which have proven to be disastrous in many countries—including here in Kenya—and we need to avoid these proven mistakes this time around. If I were in that plane, I would want the pilot to bring it down quickly and safely. While on the ground, the engines could be repaired and adjusted, as the hurricane passes by; it will take you longer to get home, but you will live to reunite with your family.

There are many measures that the government can take to get Kenya’s “economic plane” safely on the ground. One of them has been taken by the Central Bank last week when it increased benchmark interest rates from 7 to 11 percent. This can contribute to controlling inflation and the next weeks will tell if this measure was sufficient. The risk is that it will also cool the economy. While unpopular, such measures are needed to reestablish Kenya’s macroeconomic credibility and help the economy in the medium-term. This is the price to pay in order to retain investments and avoid a crash.

Join the Conversation