In the two years since the Government of National Unity (GNU) was formed and Zimbabwe dollarized fully, there have been encouraging developments on the economic front.

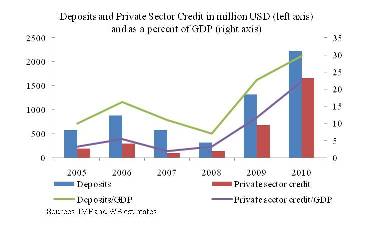

The economy grew at nine percent in 2010, following on six percent in 2009. Government revenues climbed to 29 percent GDP in 2010; they were just three percent of GDP in 2008. And the banking sector which had dis intermediated almost fully during the hyperinflation grew its dollar deposits briskly to around 30 percent of GDP at the end of 2010. But election talk has suddenly mushroomed in 2011, setting off political competition that could slow down Zimbabwe’s return to normalcy.

This good performance starts from a low base; the economy had contracted by more than 45 percent from 1999-2008. Furthermore, world prices of commodities, such as platinum, tobacco and gold, which are Zimbabwe’s main exports, have been on the rise. Weather has been good in the past two years. But the point is that Zimbabwe was able to make good use of these conditions. There was a supply response to high prices in agriculture and mining, and manufacturing showed signs of life. And importantly, some key economic institutions such as the revenue agency performed. These are the good economic genes.

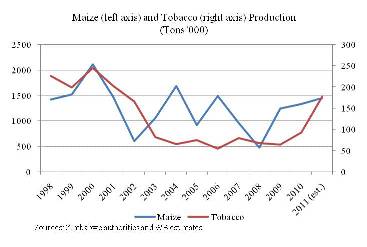

The revival of agriculture goes against commonly held wisdom. Redistribution of erstwhile large commercial farms to indigenous Zimbabweans has been largely achieved. There is a widespread concern about disputed titles and insecure tenure. Yet smallholder agriculture appears to be moving.

The number of smallholder farmers in tobacco has increased sharply. Output of tobacco, maize, and cotton is recovering. The yields are nowhere near their previous levels. But then Zimbabwean agriculture has undergone a huge structural change and some yield losses, particularly those due to the reduction in average farm size, could be permanent. The ability of farmers to respond to price incentives is a strong signal that policy distortions in the sector are minimal and markets are functioning well. In the long run structural constraints could bind however.

(Click on the graphs to see them bigger)

The second sign of good genes is the performance at revenue collection. Ability to collect taxes is a fundamental indicator of a state’s capacity and Zimbabwe has performed well on this count. The sharp climb in revenues as a share of GDP is both a sign of the capacity of the revenue collection system as well as the extent of tax base. The structure of revenues is fast returning to the previous normal whereby the share of trade taxes has declined and taxes on profits, income, and consumption are the predominant source.

The banking system has also performed well as dollar deposits and private credit grew rapidly. Deposits and credit now approach pre-crisis levels as share of GDP. These are signs of a return of confidence in the banking system.

Zimbabwe’s industrial sector remains diversified but is struggling. A recent enterprise survey team that visited Harare was surprised to note the diversity resembling that in a lower middle income country. The team decided to increase the sample size from the previously planned 150 to 600 to generate representative results for the diverse set of enterprises.

It is possible that many of the struggling companies will close down. At the same time many new companies will likely come in their place. Even when many businesses are struggling, there are others that are growing fast. And cheap broadband access through sea-cable could set the stage for IT and IT-enabled services to take-off.

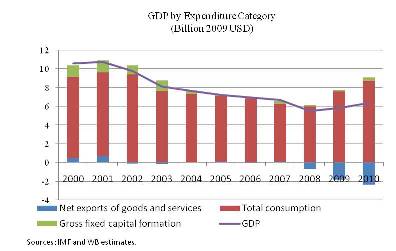

Zimbabwe has a long way to go before normalcy returns. The most recent assessment (2007-08) puts the poverty rate at 57%. Meanwhile, consumption has exceeded national income for the past several years. In 2009 and 2010, consumption was more than 20 percent above national income.

Essentially the country has been meeting its current consumption needs (and some investment such as in mining) by increasing its international indebtedness and from short term capital inflows. This situation is not sustainable and prone to significant risk. Sooner or later, the country will need to adjust consumption. A desirable adjustment will be through consumption growing more slowly than income. An abrupt adjustment of levels could result in loss of jobs and even higher poverty. Continued capital inflows are therefore important for return to normalcy.

Politics is making it harder for capital to flow in. Against the background of elections, policy differences within partners of the government have sharpened. They have become pronounced in areas such as indigenization, payroll management, civil service wages, and management of the mining sector.

The most significant recent policy move is the fast-tracking of indigenization in the mining sector. On 25th March, the government issued regulations which set September 25, 2011 as the date by which all mining businesses shall achieve the minimum indigenization quota -- measured as a controlling interest (51 percent of shares), held by indigenous Zimbabweans. The valuation of shares will be agreed to between the Government and the business, and shall take into account the State’s sovereign ownership of the minerals.

The fast-tracking has scared mining companies, and there could be spillover in other sectors as well.

It signals that Zimbabwe is less welcoming of foreign investment, something it can ill afford at this moment.

Join the Conversation