Stock trader overreaction to stock market | © shutterstock.com

Stock trader overreaction to stock market | © shutterstock.com

In his 1936 book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, Keynes coined the term “animal spirits” to argue that individuals often make economic decisions based on how they feel about the overall economy rather than through an unbiased, rational analysis of facts. This imperceptible, yet mighty, force of sentiment seems to propel the economy into periodic booms and busts. This is a force distinct from the force of rationality, which the macroeconomists have long formalized in their theoretical models as the precise, farsighted judgement of a perfectly rational, yet purely fictitious creature, the Homo-economicus.

An emerging body of empirical work has challenged the theoretical assumption of rationality. While much of the recent evidence on irrationality has been situated in the stock and bond markets, it is only natural to wonder whether such a phenomenon could also exist in the banking sector. After all, the banking sector is at the heart of the modern economy and if there are pockets of irrational behavior, then it may have first-order importance for credit, investment, and financial stability in the economy.

In a recent paper, we investigate elements of irrationality in the banking sector. To do so, we exploit the fact that banks are required by regulation to keep aside some capital as a buffer against a loan that may turn bad in the future. This buffer — or, technically, loan loss provisions — ensures that banks have an additional layer of usable capital that can be drawn upon to offset against losses incurred in the future. Naturally, estimating what fraction of loans may turn bad in the future requires the bank to form careful expectations of, well, the future. And therefore, analyzing these provisions provides a cue to tease out the expectations that the banking sector holds of the future.

Now, what makes one say whether the expectations of the future are rational or not? For that, a simple argument comes in handy: every penny that the bank puts aside as buffer is a foregone opportunity for the bank to earn income via lending. So, if the banks were perfectly capable of assessing the future, they would want to keep just enough provisions to cover the future losses. No more, no less. Surely, no one has perfect foresight, but repeated experience over a sufficiently long period would certainly suggest that such provisions should not be very different from the actual loss over the same period.

However, when we compare the expectations of future loss with the actual loss over a sufficiently long period of 25 years (for the United States), we find that the two are statistically divergent. Not only have the banks been repeatedly inaccurate in their estimations of future loss, but also there seems to be a consistent pattern of what can be termed as an overreaction bias to the prevailing macroeconomic conditions: if times are bad, banks tend to believe the future will be worse and end up over-provisioning, and if times are good, they believe the future will be better and end up under-provisioning.

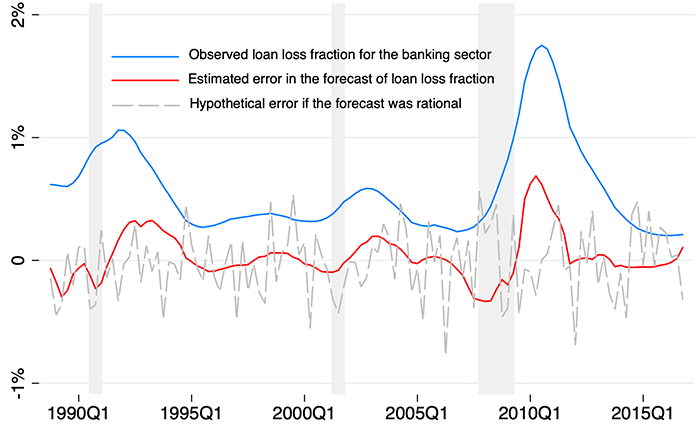

Figure 1. Bias in expectations

Figure 1 underlines this relationship. The co-movement between the actual loss fraction on the loan portfolio of banks (blue line) and the error in predicting this loss (red line) suggests a systematic variation that betrays an overreaction bias: when the actual losses are high, the banks tend to be way-off in their forecasts and vice-versa.

Whereas, if the banks were rational in their forecasts, no such systematic variation between the two would possibly exist, and in fact, the error in the forecast would very simply be some erratic shape (the grey dotted line). That the estimated error seems to be in an explicit departure from its hypothetical rational counterpart indicates that the banks tend to be biased toward a short-sighted view. More pointedly, they seem to be prey to bursts of irrational optimism and pessimism — whichever the prevailing conditions might dictate.

What is the big deal, you ask? Well, this overreaction bias distorts the buffer kept by the banking sector, which in turn affects the credit available for productive investment in the economy. This results in an aggregate credit supply that is too sensitive to the current conditions and induces instability in the financial system. Particularly in bad times, banks tend to become excessively pessimistic about the future and end up keeping excessively higher provisions. This pessimistic view further squeezes out credit supply — in times when credit is already critically scarce. This results in a double punch, debilitating the economy further.

Importantly, our analysis also reveals that the presence of bias reduces the potency of the regulatory policies, in particular, the accounting provisioning rules. Ever since the financial crisis, policy makers have attempted to design regulatory policies in the sincere hope to preempt any instability in the banking sector. However, the underlying assumption in all such policy design has always been that the banks form expectations rationally. Our findings cast doubt on commonly held assumptions about the rational Homo-economicus that inhabits economic models and policy making. For the policies to serve the intended effect, they must be fine-tuned to compensate for the extent of this bias, in particular, the overreaction bias.

In sum, we demonstrate that expectations in the banking sector display an overreaction bias to the prevailing conditions, and the presence of this bias results in a turbulent credit supply, volatile investment, and financial instability. To mitigate these undesirable outcomes, bank regulators need to embrace animal spirits in the design of their policies to achieve a more resilient banking system and a stable economy.

Join the Conversation