Central Bank Digital Currency concept | © shutterstock.com

Central Bank Digital Currency concept | © shutterstock.com

Over the past two decades, achieving “financial inclusion” as a key enabler for reducing poverty and increasing prosperity, by granting access to financial services to disadvantaged segments of society and the economy, has become a national priority in many jurisdictions worldwide (CPMI-World Bank 2016). According to a recent World Bank update, since 2010 more than 55 countries have made commitments to financial inclusion, and more than 60 have launched or are developing a national strategy.1

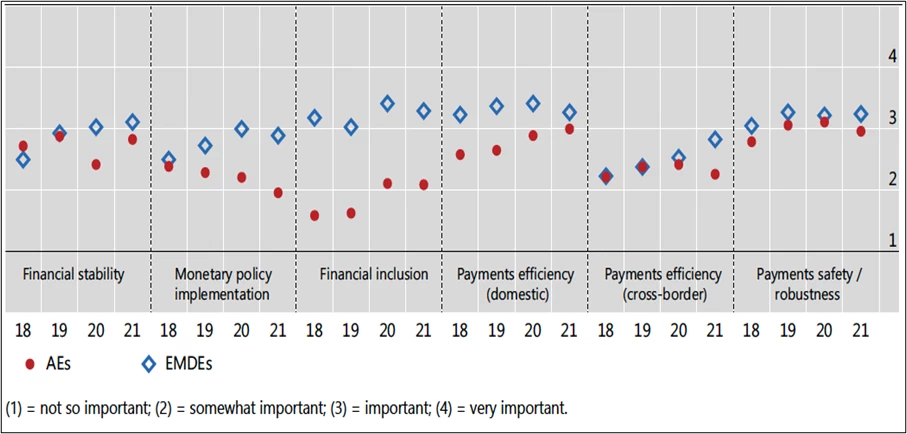

Today, boosting financial inclusion ranks high across emerging market and developing economies as a motivation for issuing retail central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) (BIS 2022). Indeed, as figure 1 shows, the CBDC engagement of these economies is driven, above all, by financial inclusion–related motivations (Kosse and Mattei 2021).

Figure 1. Motivations for issuing a retail CBDC

Source: Kosse and Mattei 2021.

It remains to be seen whether CBDC will be a major factor in facilitating the inclusion of the financially excluded. Before addressing this issue, we briefly discuss the general achievements of the financial inclusion strategy approach adopted by countries so far.

Financial inclusion: The achievements

Despite the significant efforts made over the years to include financially excluded subjects (individuals and small or very small enterprises), international evidence from multiple randomized controlled trials of financial inclusion programs shows that the results generally achieved so far have been modest and not transformative (Beck 2018). By most measures, financial inclusion has increased over the past decade. The World Bank’s Global Findex indicates an impressive increase from a worldwide average of 51 percent in 2011 to 69 percent in 2017, its most recent observation. However, this still leaves an estimated 1.7 billion adults worldwide without an account or unbanked. In addition, households’ borrowing from formal financial institutions has not matched the same pace of inclusion, registering a much milder increase, from 9 to 11 percent excluding credit card use, and from 22 to 23 percent including it.

This should not come as a surprise, after all, if one recognizes the limitations of the strategy that underpins the plurality of national financial inclusion agendas across the world. The approach considers financial exclusion as the effect of “market failure,” the inability of the market to reach excluded subjects due to the presence of barriers, or the lack of proper incentives, which impede the market’s natural operation (Clamara et al. 2014; Kebede et al. 2020).

The exclusion of disadvantaged segments of society from formal finance can be considered a “failure” only under the assumption that, if enabled to work, the market always guarantees the social optimum. Accordingly, public policies are needed that correct the (presumed) market failure by removing the barriers or setting the right incentives. It is expected that, once adopted, these policies (typically in the form of new regulations) enable the market to deploy its full social optimum potential.

But financial exclusion is not a reflection of market failure; it is rather fully emblematic of market reality: markets intervene successfully, by providing adequate supplies of goods and services, only where they find it convenient to do so, that is, where they service agents who can afford to pay remunerative prices to suppliers. It is normal that markets refrain from operating where they see no opportunities for profits or prospects for the commercial viability of businesses.

This explains why poor people, or subjects residing in remote and costly-to-reach places, are not attractive propositions to the market — unless some form of public support (for instance, in the form of direct services provision, procurement of services, subsidies to providers, etc.) improves the market’s convenience to service them. Yet, such public support would not represent a cure for a market failure. It would supplement the market where the market would be absent or uninterested to be (for perfectly justifiable reasons).

Undoubtedly, public policy can do a lot to better on the business case of some financial inclusion-related activities, and enabling strategies (such as, for instance, those based on the PAFI approach) are important to this end. However, experience shows that issuing conducive regulations and righting the incentives alone are not enough to solve the problem.

Central banks seem to be looking at CBDC as the silver bullet for finally filling the gaps of unsuccessful (or not fully successful) financial inclusion strategies. Is this justified?

This will be the subject of the second part of this commentary.

References

Beck, T (2018), “What's new in the financial inclusion literature?” VOXEU Blog/Review, 2 May.

BIS (2022), “CBDCs in emerging market economies,” BIS Papers No 123, Bank for International Settlements, April.

Clamara, N, X Peña, and D Tuesta (2014), “Factors that Matter for Financial Inclusion: Evidence from Peru,” BBVA Research, Working Paper No. 14/09, Madrid, February.

CPMI-World Bank (2016), Payment Aspects of Financial Inclusion, report by the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) and World Bank Group, April.

Kebede, J, A Naranpanawa, and S Selvanathan (2020), “Financial inclusion: Measure, and nexus with bank market structure in Africa,” Discussion Paper Series 2020-04, Griffith Business School, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia, April.

Kosse, A, and I Mattei (2021), “Gaining momentum — Results of the 2021 BIS survey on central bank digital currencies,” BIS Papers No. 125, May.

1 See Financial Inclusion Overview, The World Bank, updated as of March 29, 2022.

Join the Conversation