Financial bank adviser meeting with customers | © shutterstock.com

Financial bank adviser meeting with customers | © shutterstock.com

The past decade has not been easy for equity investors in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs). Emerging markets lag developed markets in the MSCI public index. They also lag in the Cambridge Associates’ index of private equity and venture capital performance, especially outside Asia, where one region, Latin America, has seen negative returns. In Sub-Saharan Africa, where many (including the author) saw a strong investment case early in the decade, several major fund managers are now pulling back.

These recent results raise questions about the financial case for investment outside high-income economies. Although there are examples of investors that have prospered, their experience may be an exception rather than the rule. Under what circumstances do EMDEs outperform developed markets?

My colleagues and I answer this question in a new study of a remarkable data set—the cash flows associated with every private equity and venture capital investment made by the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private-sector arm of World Bank. This data set offers three advantages compared with existing references. First, the time series is longer than any other available, reaching back to 1961. Second, due to the IFC’s mandate to promote economic development, the portfolio is extremely diversified, more so than foreign direct investment inflows, covering 130 economies with a concentration in the poorest (i.e., those with real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita less than $1,000). Third, since the data set includes all of IFC’s equity investments—even the write-offs—our analysis is not affected by survivorship bias, which occurs when successful investments are more likely to appear in a data set than failures.

Overall, we find that this portfolio has outperformed the S&P 500 by 15 percent since 1961. In comparison, the median leveraged buyout fund in developed economies, which also invests in private equity, outperformed the S&P 500 by 16 percent. So long-run returns comparable to those in developed markets can be achieved through a global, diversified emerging market strategy and when the aim is to have positive impact alongside financial return.

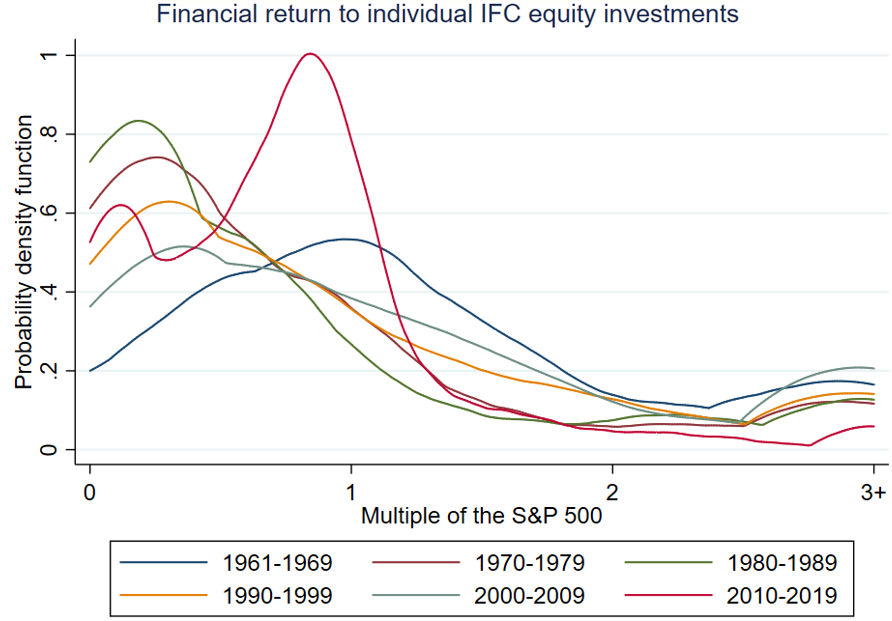

Figure 1: There is substantial variance in performance of investments within the portfolio

Notes: The multiple of the S&P 500 is calculated as the public market equivalent (PME), a measure of financial return that compares the investment to an equivalently timed investment in the public index. The PME is preferred to alternative measures of return (i.e., the internal rate of return, multiple of money) because the PME accounts for the value of payouts that are less correlated with the market, as in the capital asset pricing model. Investments in the chart are grouped by vintage year—the year of first cash flow.

There is large variance in returns across investments within this strategy (Figure 1). Our analysis identifies three factors that drive investment performance at the country-level, providing insight for any international investor who contemplates investing in EMDEs to realize an above market return on equity.

First, go where others do not. Economic theory suggests that to achieve superior returns, investors need to identify markets where they face less competition. Consistent with this idea, IFC’s returns have been highest in the economies where it is hardest for other investors to operate. Within countries, returns tend to fall when countries relax the capital controls recorded in the International Monetary Fund’s Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions, making it easier for other investors to enter. Deepening of the banking system is also associated with lower returns. An increase in the private sector credit-to-GDP ratio of the magnitude experienced by Brazil from 1990 to 2020 is associated with a 4.9 percent lower annual excess return (versus the S&P 500) on the average investment.

Second, focus on the forecast of macroeconomic fundamentals, rather than the situation at the time of investment. A surprising result is that country risk factors, including political risk, perceived corruption, and the ease of doing business, do not significantly predict financial performance when measured at the time of investment. However, macroeconomic conditions over the course of the investment have material effects, with a 1 percent increase in cumulative annualized real GDP growth over the life of an investment increasing the annual excess return by almost 1 percent.

Third, patient capital is rewarded. Unlike a fund that must liquidate over a short time horizon—typically five years—the IFC operates more like a holding company, holding equity investments for longer, around eight years on average and often much longer. This turns out to be a key to financial success, especially in EMDEs where macroeconomic volatility can harm performance in the short run. In our data set, longer holding periods are associated with stronger performance at the investment level, even when controlling for sector and vintage year.

There are of course some caveats.

First, the IFC’s membership in the World Bank Group for instance may afford it particularly strong protection from expropriation—although the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency does sell expropriation insurance, which can be purchased by private investors. Nonetheless, given it is the only international investor with a portfolio spanning such a large and diverse set of countries and because it co-invests with several funds, the portfolio still provides a unique view of the returns to private investment in EMDEs.

Second, when restricting the portfolio to only investments with vintage years including 2010 and after, performance has been considerably worse than the S&P 500, although still on par with the MSCI EM index, which the IFC targets. An explanation could be that fewer investments in the recent decade (just 26 percent) have been realized, and there has not yet been time for the benefits of patience to play out. Another explanation, which would explain the recent underperformance of EMDEs in other data sets, is that international capital markets are now better integrated than they were when the IFC was founded, and there are today fewer opportunities to go where other investors do not.

The best investment strategy is often to buy and hold the public index. The IFC’s experience shows that historically one can do better in private equity by buying and holding companies in the right economies. To find these economies, investors should focus on the growth forecast, rather than political risk or regulation, and seek the economies where there is less competition from other investors, due to a less developed banking system or capital controls . Quantitatively, finding a market with less competition appears to be even more important for returns than growth.

Although there may be fewer economies that fit this profile today than in the last century, there are still a few. Potential examples are Ethiopia and Myanmar, two large countries with closed economies that are nonetheless expected to grow rapidly.

Join the Conversation