Flying paper money planes. | © shutterstock.com

Flying paper money planes. | © shutterstock.com

Capital controls, residency-based or currency-based measures used to regulate cross-country financial flows, are increasingly considered part of the standard financial stability policy toolkit for many emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs). During the first quarter of 2020, the COVID-19 crisis caused unprecedented capital outflows from EMDEs, further highlighting the need for better understanding of capital flow management.

A widely held view in the recent academic literature and policy institutions is that national authorities can mitigate the effects of inefficient and destabilizing capital inflows by the active use of capital controls. However, as has been found for other types of macroeconomic policies, an announcement of policy changes conveys not only the action itself, but also information about the authorities' views on the state of the economy. Rational market participants can be expected to learn from policy announcements and adjust their information set accordingly (Nakamura and Steinsson (2018) explore this in the context of U.S. monetary policy). My recent paper explores this theme for capital controls: the paper shows that capital controls convey useful information about economic fundamentals and this can dampen the effectiveness of capital controls in mitigating the effects of excessive capital inflows.

Measuring the information content of capital controls

In the empirical section, I provide some evidence that people learn about economic fundamentals from capital control policy announcements from an event study of capital control announcements in Brazil and an exercise nowcasting1 Brazilian real gross domestic product (GDP). Between 2006 and 2013, the country experienced large and volatile capital inflows and actively used capital controls to manage such inflows with some recognized success, and hence my focus on the country.

Event studies using high-frequency data show that expectations of economic fundamentals in Brazil respond meaningfully to major capital control announcements. Specifically, I use daily survey data on market participants' median expectation of quarterly real GDP growth collected by the Central Bank of Brazil and consider six major capital control announcements in the country between 2008 and 2013. On average, a tightening (loosening) announcement is associated with a downward (upward) revision of the real GDP growth forecast of 0.23%.

Since the survey data average many forecasters' expectations constructed with different methodologies, and hence can be hard to interpret in greater detail, I provide a complementary set of empirical evidence by taking a stand on how to form expectations of fundamentals. Specifically, I put myself in the position of a forecaster who employs a commonly used econometric model (e.g., Giannone, Reichlin, and Small 2008) and uses all types of available macroeconomic data to produce nowcasts of Brazilian quarterly GDP growth rates in real-time. Including capital control announcements in the forecaster's information set helps improve the precision of the nowcast. The framework allows for the measurement of such improvement, that is, the information conveyed, alongside other types of data (figure 1)

Figure 1. Mean forecast error reduction of different types of data

Note: This chart shows the mean forecast error reduction of different types of data in a nowcasting model of Brazilian quarterly real GDP growth. The data blocks are ordered by timing of release.

Implications of learning from capital controls for policy efficacy

To study the implications of learning from capital controls for the efficacy of such policies, I incorporate learning from policy into a standard type of model researchers use to study capital controls in EMDEs (e.g., Bianchi (2011) and Mendoza (2010)). In this two-sector small open economy model, borrowing by domestic agent is limited by tradable and nontradable income through a collateral constraint. This environment features a pecuniary externality because the private sector does not internalize the effect of its borrowing decisions on the value of collateral and hence on borrowing capacity. Capital controls are usually deployed by the government to mitigate the effect of over-borrowing by the private sector arising from the pecuniary externality.

I incorporate three novel features in this setting to model learning from policy. First, the government knows more about future economic fundamentals than the private sector does.2 Second, the private sector knows that the government is levying capital control taxes according to a simple policy rule that reveals useful information that was previously unknown to the private sector. Finally, the private sector learns from policy by completing a Bayesian updating of its information set when it observes policy changes.

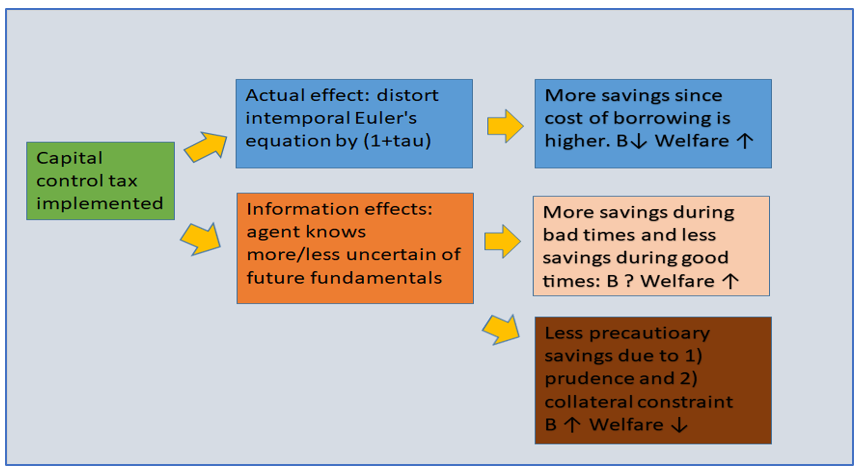

My model is calibrated to the Brazilian economy and the quantitative model features unintended consequences of capital controls when policy conveys information about economic fundamentals. When the private sector learns from policy, the domestic economy borrows more from foreign countries and experiences more severe financial crisis in the sense of larger consumption drops, real exchange rate depreciations, and capital outflows relative to the cases of (1) no policy interventions and (2) no learning from policy interventions. This is because the private sector is less uncertain about the future and saves less for precautionary reasons. In this setting, learning and information revelation reduce precautionary savings precisely when such savings mitigate the pecuniary externality (see figure 2 for the main model mechanisms).

Figure 2. Model mechanisms

Note: There are three effects of capital controls in the model with information and learning, an actual effect and two additional information effects. Tau is the tax rate on foreign borrowing, which represents capital controls in the model. B is the level of foreign borrowing by the domestic economy.

Take-away for policy makers

The findings of this paper could have important implications for policy makers. In designing capital flow management policies, authorities must take into consideration that the environment in which they operate is not invariant to policy actions : it changes as information about the environment is perceived to be transmitted through policy actions, a well-known critique of other macroeconomic policies (Kydland and Prescott 1977). However, my findings do not necessarily imply that clear communication of underlying fundamentals is undesirable: such communication has benefits in relieving information frictions (figure 2, second mechanism), and hence it should be carefully balanced against the undermining of policy efficacy in mitigating the pecuniary externalities stressed in this paper.

References

Bianchi, Javier. “Overborrowing and Systemic Externalities in the Business Cycle,” American Economic Review, 101(7), 2011, pp. 3400-3426.

Giannone, Domenico, Lucrezia Reichlin and David Small. “The Real-Time Informational Content of Macroeconomic Data,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 55, 2008, pp. 65-676.

Kydland, Finn E., and Edward C. Prescott. “Rules Rather Than Discretion: The Inconsistency of Optimal Plans.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 85, no. 3, 1977, pp. 473–491.

Mendoza, Enrique. “Sudden Stops, Financial Crisis and Leverage," American Economic Review, 100(5), 2010, pp. 1941-1966.

Nakamura, Emi and Jon Steinsson. “High Frequency Identification of Monetary Non-Neutrality: The Information Effect," Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 133, Issue 3, 2018, pp. 1283–1330.

1 Nowcasting refers to forecasting of the very near future.

2 A real-world example is as follows: a financial regulator is charged with the mandate of maintaining financial stability. Hence, the regulator accumulates knowledge and gains expertise through research in this subject area, information collection authorized by the law, onsite examination of financial institutions, stress tests, and other activities. The regulator does not know more than a private sector firm about how to run its business, but it does know more about the overall state of what it regulates.

Join the Conversation