In the past three decades the role of state-owned banks has been sharply reduced in most emerging economies. This reflects a general disappointment with their financial performance and contribution to financial and economic development, especially in countries where they dominated the banking system. But despite their loss of market share, state banks still play a substantial role in many regions, especially in East Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and South Asia (figure 1).

Figure 1 Share of state banks in total assets by region, various years, 1970–2005

(percent)

The arguments put forward to justify the continuing presence of state banks have included market failures (resulting from asymmetric information and poor enforcement of contracts) that restrict access to credit; the provision of essential financial services in remote areas (where supply may be restricted by large fixed costs); and the provision of countercyclical finance to prevent an excessive contraction of credit during a financial crisis. These arguments may well justify policy interventions in many countries, although it does not necessarily follow that state banks are the optimal intervention. Moreover, even where the presence of state banks may be justified, policy makers still face the challenge of ensuring clear mandates and sound governance structures in order to minimize political interference and avoid large financial losses.

The decision on whether state banks should continue to play a role in the financial system therefore entails a careful consideration of benefits and costs. In making this decision, policy makers should take into account many factors, including the past performance and contribution of state banks in their countries and elsewhere.

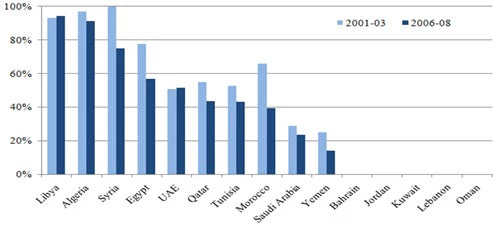

The Middle East and North Africa is one of the regions where state banks have lost market share but still play an important role in many countries (figure 2). In the aftermath of the recent global financial crisis, policy makers in these countries have been considering whether they should further reduce the role of state banks. An analysis of the performance of state banks in the region can provide useful inputs for this decision.

Figure 2 Share of state banks in total assets in selected countries, 2001–03 and 2006–08

(percent; average for period)

Providing such an analysis is the main objective of a paper I recently wrote with Subika Farazi and Erik Feyen. While we examine ownership trends for the entire region, we focus the statistical analysis of bank ownership and performance on countries that are not members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (non-GCC countries) because state ownership is more prevalent, and the distinctions between public and private ownership more relevant and consequential, in these countries.

Our results show that state banks are significantly less profitable than private banks in the non-GCC group. The lower profitability probably reflects a combination of policy mandates and operational inefficiencies. In particular:

- State banks provide more finance to the government than private banks do, a result that may reflect a government financing mandate and that contributes to lower net interest margins and profitability.

- State banks have much higher ratios of overhead costs to assets (with their larger sizes and balance sheet structures controlled for), primarily because of much higher ratios of employees to total assets. This result could reflect a mandate to expand access in remote areas or simply their outdated technologies and staff redundancies.

- State banks tend to generate much higher levels of nonperforming loans (NPLs), which translate into larger loan loss provisions and ultimately lower profitability. These results probably reflect the imposition of various development mandates on state banks, combined with their lack of efficiency in fulfilling these mandates.

Therefore, one could in principle argue that the weaker performance of state banks might be justified by their development mandates. But our analysis shows that the effectiveness of state banks in fulfilling these mandates has been mixed:

- State banks in the non-GCC countries of the Middle East and North Africa have larger branch networks, and success in expanding access in remote areas could explain the larger overhead costs. Yet we find no evidence that these banks have made a significant contribution to access as measured by the number of deposit accounts per adult.

- There is evidence that state banks have contributed to finance for small and medium-size enterprises, but there is also evidence that they lack the capacity to manage the associated risks (Rocha and others 2011). This lack of risk management capacity is consistent with their lower skill base and has probably contributed to the poor financial results, including higher NPLs, higher levels of loan loss provisioning, and ultimately lower profitability.

- Another key mandate is housing finance, where state banks in Algeria, the Arab Republic of Egypt, Morocco, the Syrian Arab Republic, and Tunisia took the lead to develop a market that had been nonexistent. Yet despite initial successes, political interference in pricing and client screening as well as a lack of competition and skills led to large losses and subsequent bailouts.

- State banks seem to play a key role in providing long-term investment finance, and this role seems particularly important in countries where they hold a large market share and serve a large number of state enterprises, such as Algeria, Egypt, Libya, and Syria. But these are also the countries where the banking system generates the largest ratios of NPLs to total loans, suggesting again that state banks have not fulfilled this mandate effectively.

- There is no compelling evidence that state banks in non-GCC countries played a significant countercyclical role in the recent financial crisis.

We conclude by saying that state bank interventions may come at a significant cost. Some of these costs are a result of the mandates themselves; others are a result of excessive political interference, poor governance structures, and operational deficiencies of these banks. There is scope for reducing the market share of state banks, especially in the countries where they still hold very large shares and dominate financial intermediation—Algeria, Libya, and Syria. There is also scope for clarifying the mandates, improving the governance structures, and strengthening the operational efficiency of most or all state banks in the region. Middle Eastern and North African countries that do not have state banks may not find it necessary to create ones, because they have been addressing their policy objectives through alternative and probably more effective policy interventions, such as credit guarantee schemes.

Further reading

Farazi, Subika, Erik Feyen, and Roberto Rocha. 2011. “Bank Ownership and Performance in the Middle East and North Africa Region.” Policy Research Working Paper 5620, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Rocha, Roberto, Subika Farazi, Rania Khouri, and Douglas Pearce. 2011. “The Status of Bank Lending to SMEs in the Middle East and North Africa Region: The Results of a Joint Survey of the Union of Arab Banks and the World Bank.” Policy Research Working Paper 5607, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Join the Conversation