Women working in Gaza. (Photo:Majdi Fathi)

Women working in Gaza. (Photo:Majdi Fathi)

Globally, poverty has been decreasing since the early 1990s, but a slowdown in the rate of decline in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) was observed even before the pandemic hit. In fact, MENA has been the only region to experience rising levels of poverty since 2013, with a dramatic increase in extreme poverty (those living on less than US$1.90 a day) observed between 2011 and 2018, when it rose from 2.4% to 7.2%.

Now, all regions face the prospect of setbacks. The World Bank estimates the pandemic led to 97 million more people being plunged into poverty worldwide in 2020 than would have been otherwise. How has COVID-19 affected the welfare both of individuals and of households in MENA? And what issues should policymakers focus on to facilitate a quick and sustainable economic convalescence?

A new report — Distributional Impacts of COVID-19 in the Middle East and North Africa — explores these questions by analyzing primary data newly gathered in the region, largely through high-frequency phone surveys, and complementing it with projections, carried out through microsimulations that allow us to make assessments of the impact on poverty and inequality.

One of the report’s key findings is that the pandemic has had an unequal impact on people, often affecting the poor and vulnerable disproportionately. This is particularly worrisome, given that before the pandemic MENA was already grappling with low annual growth, high rates of unemployment, high levels of informality, low female labor force participation, a lack of quality jobs, an unconducive business environment, food insecurity, and fragility and conflict.

Policymakers will need to move quickly to minimize an escalation of poverty and provide income and social support to those worst hit, albeit with fiscal prudence. Otherwise, there is a serious risk that MENA’s already fragile social fabric will be further torn apart.

Losing Ground on Poverty Front

How will the unequal impacts be manifested? The results suggest: (i) a substantial rise in poverty; (ii) greater inequality; (iii) the emergence of a group of “new poor” (those who were not poor in the first quarter of 2020 but have become poor since); and (iv) changes in the labor market at both the intensive (how hard people work) and extensive (how many people work) margins. The report estimates that poverty in MENA will rise significantly in 2020—depending on the country or economy, anywhere between 5 and 35 percentage points—particularly in countries like the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon, where COVID-19 is compounding other economic ills.

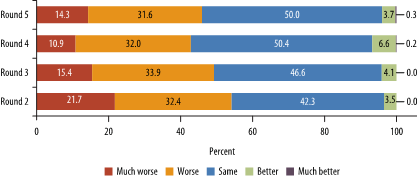

Starting with changes in welfare: in Tunisia, more than half of the households interviewed in five rounds of the phone survey reported the pandemic had led to a drop in living standards compared with the period prior to the outbreak, that is March 2020 (see figure). This was seen particularly among those in the bottom 40% of household consumption from mid-May to mid-October, 2020. This severe fall in household welfare as the pandemic unfolded extended well beyond the end of restrictions on individual mobility. A similar pattern was found in Egypt during rounds 1 and 2 of the survey, with the bottom 40% of households most affected.

About Half of Tunisian Households Report a Decline in Living Standards

Self-reported change in household living standards since before the pandemic, by survey round

Source: World Bank calculations, based on data from Enquète téléphonique auprès des ménages pour étudier et suivre l’impact due COVID19 sur le quotidien des Tunisiens, rounds 1 to 5 (survey conducted by National Institute of Statistics and the World Bank).

Note: Round 2 was conducted May 15–21; round 3, June 8–15; round 4, June 22–30; and round 5, October 4–16.

In addition, the MENA phone surveys show that the degree of loss varies across households, based on socioeconomic characteristics—like wealth, gender, employment sectors, the nature of employment contracts, and location (urban or rural). The most vulnerable (those in poor or almost-poor households) have been employed in sectors that have felt the highest impact of the pandemic: extractive industries, tourism (including hotels, cafes, and restaurants), retail trade, transport, commerce, and construction. These are the sectors where, typically, informal daily-wage earners or those in contractual (temporary) jobs are employed, and where the option of telecommuting or remote working is not available.

Another particularly vulnerable group is refugees. In Lebanon, the increase in poverty for nationals (the host community) is estimated at 13 percentage points for 2020 from the 2019 baseline, and 28 percentage points for 2021. But for Syrian refugees, the increases are an estimated 39 percentage points for 2020 and 52 percentage points for 2021. In Djibouti, 7% of refugees (mostly from Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, and more recently, Yemen) living in urban areas reported losing their job relative to the previous week, versus 3% of nationals. This exacerbates existing vulnerabilities, as it adds to the 25% of refugees who were already not working, compared with the 11% of Djiboutian nationals.

Join the Conversation