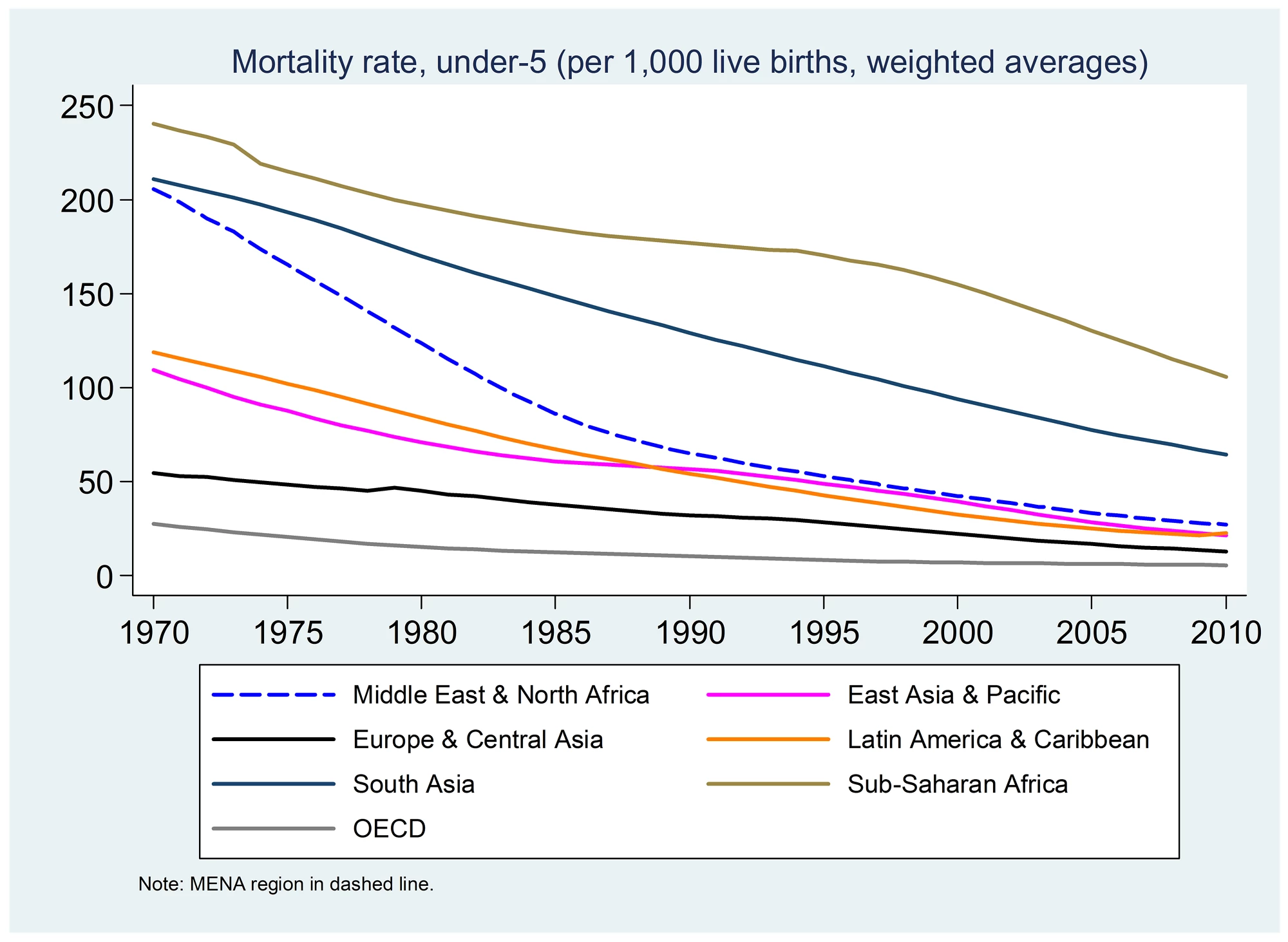

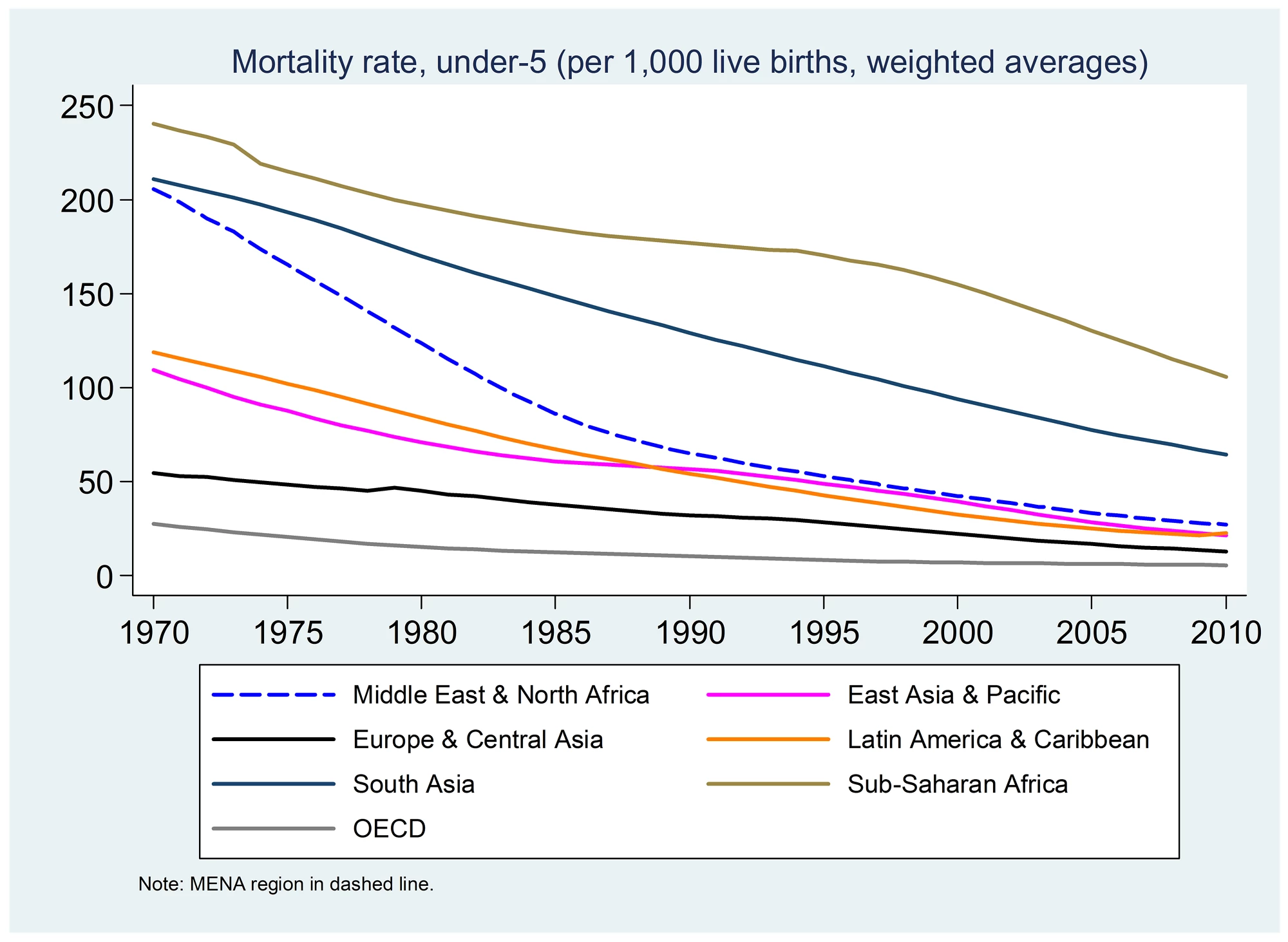

Child mortality rates have declined across the developing world over the past four decades and the best performing region in this regard has been the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

Child mortality rates declined in MENA from a level of 206 per 1,000 live births in 1970 to only 27 in 2010. This was the biggest absolute reduction (179 points) among world regions as well as the biggest percentage reduction (87 points). In comparison, Latin America and East Asia, the next best performing regions, achieved percentage declines of 81 and 80 points respectively, over the same period.

MENA’s comparatively faster rate of child mortality decline can be seen clearly in the chart below.

This shows that, alone among the developing country regions, MENA jumped from the higher rate cluster of South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (in 1970) and joined the lower rate cluster of Latin America and East Asia (by the 1990s).

Disaggregating MENA’s performance to the country level reveals some remarkable achievements when countries are ranked by percentage decline in child mortality rates over 1970-2010:

One possible explanation may lie in the widespread MENA practice of subsidizing basic food items. While such subsidies are costly from a fiscal point of view and inefficiently targeted, it is generally acknowledged that they have a positive impact on the nutrition standards of lower income families. Of course, more research is needed to establish whether MENA is distinctive in providing such food subsidies as countries in other regions as well have had similar practices at various times.

The time profile of MENA’s performance points to some sobering implications for the future. For example, after 1990, MENA’s trajectory of child mortality decline has been no different from that of Latin America and East Asia and less rapid than that of South Asia and, in more recent years, Sub-Saharan Africa as well. This may be due in part to the fact that it is easier to cut rates from very high levels but more difficult to do so when mortality rates are already low. So the region will have to try even harder in the future to get results similar to those achieved in the past.

So while it is still appropriate to describe MENA’s experience with child mortality as an historical success story, one should probably put the emphasis on the historical part.

Child mortality rates declined in MENA from a level of 206 per 1,000 live births in 1970 to only 27 in 2010. This was the biggest absolute reduction (179 points) among world regions as well as the biggest percentage reduction (87 points). In comparison, Latin America and East Asia, the next best performing regions, achieved percentage declines of 81 and 80 points respectively, over the same period.

MENA’s comparatively faster rate of child mortality decline can be seen clearly in the chart below.

This shows that, alone among the developing country regions, MENA jumped from the higher rate cluster of South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (in 1970) and joined the lower rate cluster of Latin America and East Asia (by the 1990s).

Disaggregating MENA’s performance to the country level reveals some remarkable achievements when countries are ranked by percentage decline in child mortality rates over 1970-2010:

- Oman and Saudi Arabia were the second and third best performers in the world

- Ten MENA countries (Oman, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Algeria, UAE, Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, Qatar and Bahrain) rank in the top twenty-five countries in the world (out of 165)

- All but two MENA countries (these being Iraq and Jordan) rank above the global median

- Even Yemen, which has the highest child mortality rate currently among Arab MENA countries, ranks above the global median in historical performance; it was able to bring its child mortality rate down from 321 per 1000 in 1970 to 64 by 2010

One possible explanation may lie in the widespread MENA practice of subsidizing basic food items. While such subsidies are costly from a fiscal point of view and inefficiently targeted, it is generally acknowledged that they have a positive impact on the nutrition standards of lower income families. Of course, more research is needed to establish whether MENA is distinctive in providing such food subsidies as countries in other regions as well have had similar practices at various times.

The time profile of MENA’s performance points to some sobering implications for the future. For example, after 1990, MENA’s trajectory of child mortality decline has been no different from that of Latin America and East Asia and less rapid than that of South Asia and, in more recent years, Sub-Saharan Africa as well. This may be due in part to the fact that it is easier to cut rates from very high levels but more difficult to do so when mortality rates are already low. So the region will have to try even harder in the future to get results similar to those achieved in the past.

So while it is still appropriate to describe MENA’s experience with child mortality as an historical success story, one should probably put the emphasis on the historical part.

Join the Conversation