The events of the Arab Spring took the world by surprise: there were no obvious signs of an approaching storm in the Levant and the Maghreb. Objective measures—used on a regular basis—showed that economies in these parts of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) grew at a moderate pace, had low and declining rates of absolute poverty, low-to-moderate income inequality, as well as decreasing child mortality rates and increasing levels of literacy and life expectancy.

The events of the Arab Spring took the world by surprise: there were no obvious signs of an approaching storm in the Levant and the Maghreb. Objective measures—used on a regular basis—showed that economies in these parts of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) grew at a moderate pace, had low and declining rates of absolute poverty, low-to-moderate income inequality, as well as decreasing child mortality rates and increasing levels of literacy and life expectancy.

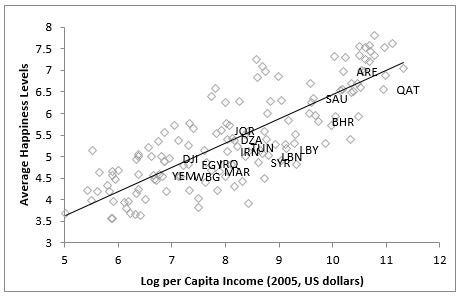

Yet, the emergence of social discontent in Arab countries could have been detected using other measures—like perceptions data. For, despite progress in their economic and social development in the 2000s, many MENA countries’ average levels of happiness were below the level expected for their per capita income (see figure below). Happiness levels were particularly low in Syria and Libya.

GDP per Capita and Satisfaction with Life, 2008–10

Source: Arampatzi, Burger, Ianchovichina, Röhricht, and Veenhoven (2015). Note: See country code abbreviations .

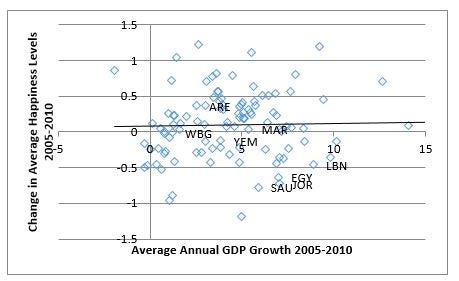

Importantly, average levels of happiness had deteriorated significantly in the years prior to the events of the Arab Spring (see figure below). The declines were larger for the middle class than they were for the poor, and they were particularly pronounced in Syria, Egypt, Tunisia, and Yemen, where the Arab Spring uprisings would become the most intense.

Declines in Happiness Levels in the Second Half of the 2000s

Source: Gallup World Poll data based on the question: “ Please imagine a ladder with steps numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?”

This situation of declining levels of happiness in combination with moderate-to-rapid progress in economic development fits the so-called “unhappy development” paradox depicted in the figure below where most Arab countries are clustered in the lower right corner. In other words, these countries grew richer but people in them also became less happy during the period from 2005–10.

Growth in GDP per Capita and Change in Life Satisfaction

Source: Arampatzi, Burger, Ianchovichina, Röhricht, and Veenhoven (2015).

Why were Arab people so unhappy despite the improvements observed in socio-economic statistics? In a recently released World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, we examine different explanations for the unhappy development paradox in the developing Arab world, including: (1) the political system of autocracy and limited civil freedoms; (2) the low standards of living; (3) high unemployment and poor quality jobs, and (4) corruption and crony capitalism. And, in explaining the level of happiness, we take into account not only the objective conditions in countries, but also inhabitants’ perceptions regarding different aspects of life and society.

We find that social discontent in the developing Arab world has been primarily driven by poor or worsening standards of living, labor market conditions, and crony capitalism. These findings highlight the importance of capturing both people’s expectations and their perceptions of quality-of-life factors that are not normally captured by objective data.

As the region’s gradually improving economic and social conditions increased expectations of a better life, many people—especially among the middle class and youth—became more aware of their standards of living and dissatisfied with them. There was growing and wide-spread frustration at the poor quality of public services, poor labor market conditions, and also at the importance of having to use informal connections (known as wasta) to members of business and political elites for getting good jobs and overcoming red tape.

How though was the increasing dissatisfaction prior to the Arab Spring linked to the protests? We find that the same grievances that had negatively affected a feeling of satisfaction with life in developing Arab countries, ultimately precipitated the Arab Spring uprisings.

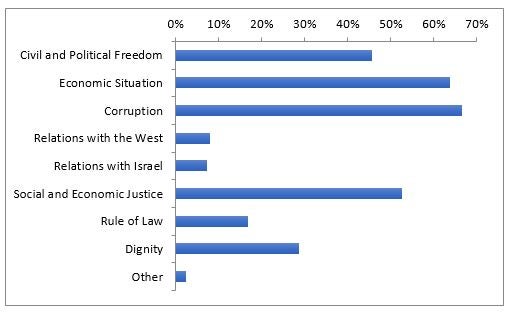

Data from the Arab Barometer cited the three main reasons respondents gave for the Arab Spring as: wanting to fight corruption, to seek better economic conditions, and to have a greater sense of social and economic justice. In other words, the declines in the average levels of life satisfaction in these countries were a precursor to the events of the Arab Spring that started at the end of 2010.

Although dissatisfaction alone does not bring about uprisings, and not every developing Arab country experienced social discontent to the same degree, we believe that the events of the Arab Spring could have been better anticipated using perceptions data. If politicians, policymakers, and scholars had focused more on the perceptions data available, they would have observed that, prior to 2011, something was amiss in the Arab world.

Reasons Why the Arab Spring Occurred According to People in the Developing Arab World

Source: Arab Barometer (2012-2014).

Join the Conversation