While he is undoubtedly a great player, Lionel Messi may not be the best person to learn from when working on your soccer game. This is not because his team lost to Germany in this year’s World Cup, but that his playing style is likely very different from yours. The next steps on your path to improvement may be closer to a better player on your own team than that of the super-star. Similarly, many policy makers and researchers look at the top scorers on international tests to improve their system’s performance, and indeed these top scorers may have a lot to teach us. However, we may learn more effectively from high-performers in our own backyard than superstars from across the globe.

While he is undoubtedly a great player, Lionel Messi may not be the best person to learn from when working on your soccer game. This is not because his team lost to Germany in this year’s World Cup, but that his playing style is likely very different from yours. The next steps on your path to improvement may be closer to a better player on your own team than that of the super-star. Similarly, many policy makers and researchers look at the top scorers on international tests to improve their system’s performance, and indeed these top scorers may have a lot to teach us. However, we may learn more effectively from high-performers in our own backyard than superstars from across the globe.

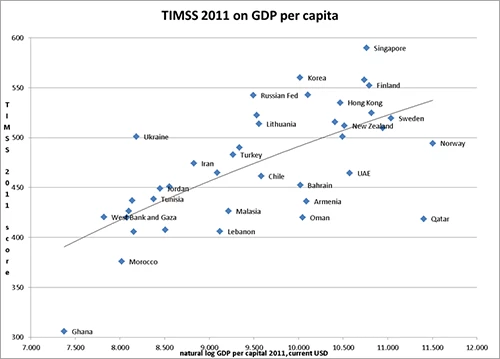

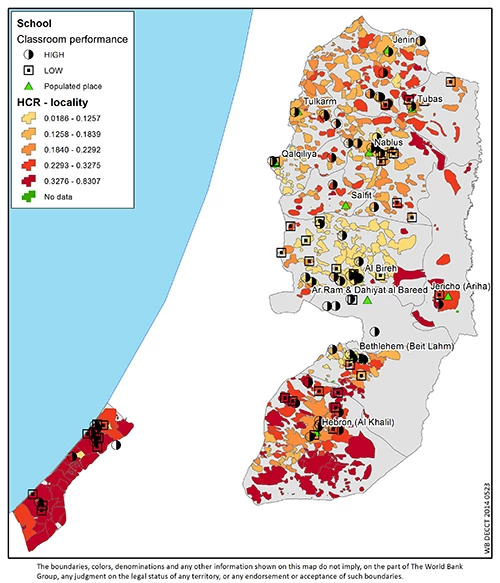

We used this local high-performers approach in a study conducted with the Palestinian Ministry of Education. We looked for “positive deviants” in the local school system, schools which managed to produce students who performed well on the Trends in International Mathematics and Science study (TIMSS) 2011 and other tests. These schools had resource levels similar to those of schools whose students didn’t do as well. So what was the difference?

We found that teachers of these high-performing classes tend to use more student discussion in the classroom, have a higher proportion of students engaged in learning in a given class period, receive greater support and conduct more outreach to parents. We also found some differences in how these schools were managed, particularly in terms of school mission and behavior policies and expectations.

None of this is shocking – past studies and even personal experience demonstrate that teachers who keep their students engaged are likely to get better results. The key difference here is that these high-performing teacher’s don’t all live in Finland and Shanghai – they are in the school down the street or in the classroom down the hall. This means that a number of the initial steps to system improvement in places such as the Palestinian Territories are readily available and can be mobilized through activities such as peer-learning, mentoring and other teacher and school director support activities.

We uncovered these trends using a number of different tools. First, we looked at the performance of different 4 th and 8 th grade classrooms on TIMSS 2011. We also looked at high and low performers on the Palestine National Assessment exam in 2012. We focused on 78 classrooms that had the top scores (equivalent to 475 or higher for both math and science on TIMSS), and visited these schools and classrooms. We also looked at 44 of the lowest performers (equivalent to 350 or lower for TIMSS). We interviewed teachers about their teaching practices and support. We interviewed school directors about school culture and resources. We also used a school facility questionnaire to investigate the physical properties of the school. We sat in classrooms and watched teachers teach, noting how much time they spent on different types of activities.

Messi is still a great player, and the superstars of the international assessments do have important lessons to teach us. Nonetheless, there are also good players close to home, and they may be more willing than the Argentinian team to help us with our technique.

Join the Conversation