Aerial view of submerged city

Aerial view of submerged city

This past year offered a glimpse of what a warmer world could bring. Multiple tornadoes left a trail of destruction across the midwestern United States. Fatal rains inundated vast swathes of land from China to South Sudan. Forest fires burned through millions of acres around the Mediterranean Sea.

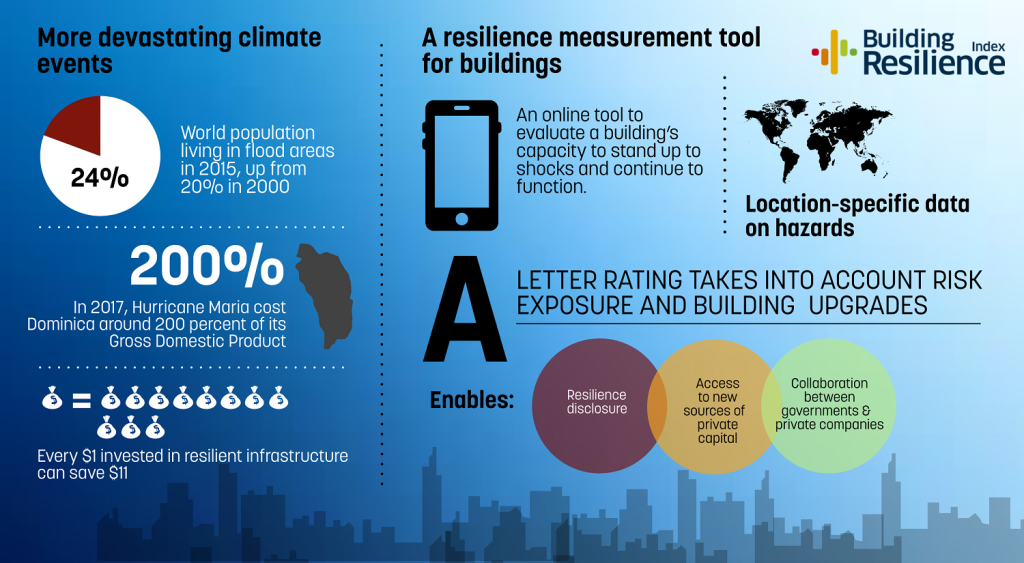

The list of extreme events keeps growing even as populations living in hazardous areas continue to become more dense.

The cost of rebuilding is also increasing. According to some estimates, disasters caused $210 billion worth of damage around the world in 2020: that’s about a third more than in 2019. In the most exposed countries – such as in the Caribbean – rebuilding after a disaster may become prohibitively expensive. In 2017, for instance, Hurricane Maria cost Dominica around 200% of its Gross Domestic Product.

Investing early to make buildings more resilient and erecting them in more secure locations are crucial ways to save lives, minimize costs, and protect development investments. The net benefit of investing in the resilience of infrastructure in low- and middle-income countries would amount to $4.2 trillion, with $4 in benefit for each $1 invested.

"Investing early to make buildings more resilient and erecting them in more secure locations are crucial ways to save lives, minimize costs, and protect development investments."

Data needed to assess risk

The business case is clear. So why have countries around the world been slower than anticipated to put these principles into practice? Emerging economies face a shortage of reliable data when it comes to assessing the costs and benefits of investing in resilient infrastructure in any given location. These include limited metrics to consistently assess local climate risks and invest in mitigation measures, and lack of disclosure regarding the level of resilience of buildings.

This has made it much more difficult for insurers, developers, investors and governments to make decisions based on real evidence and shape the real estate market of tomorrow.

Several countries have piloted efforts to fill those data gaps. For instance, the government of the Philippines – a hotspot for a range of natural disasters - has developed a mobile application allowing users to generate their own local maps showing the level of hazards associated with volcano eruptions, typhoons and many other potential disasters.

The tool is now being used by the country’s largest financial institution, Bank of the Philippine Islands. The bank evaluates its portfolio and clients’ exposure to physical climate risks and makes key investment decisions accordingly.

Building Resilience Index measures exposure to hazards

This brought a few breakthrough ideas to fruition within our team at the International Financial Corporation (IFC). We developed the Building Resilience Index, an online tool which uses a standardized letter grade rating system to evaluate a building’s capacity to stand up to shocks and continue to function. The tool can be applied to residential properties, schools, hospitals or any other type of construction.

Developed with support from the governments of Australia and the Netherlands, the index measures a building’s exposure to natural hazards and factors in the upgrades already made to mitigate these risks.

The index effectively mirrors and complements our EDGE tool, which certifies green buildings around the world, by adding a climate adaptation lens to our work in this industry. For instance, is a building situated in an area that’s prone to floods? Does it have the structural design to withstand inundations and keep occupants safe?

We expect that the Building Resilience Index will have a number of enabling effects on the market.

- First, the tool will allow a diversity of stakeholders - including financial institutions, insurers, and governments - to assess and disclose the resilience of their projects or portfolios, and to make more informed decisions on where to invest.

- Second, developers with limited access to capital for designing and constructing more resilient buildings will find new ways of attracting investors and tap into new sources of municipal finance.

- And third, the index will enable private sector entities to work more closely with governments, shaping land use regulations and building codes that govern where and what to build.

While the Philippines was a natural candidate for our pilot project, we anticipate that many more countries around the world may benefit from the next roll-out phase.

To learn more, contact Ommid Saberi, IFC Senior Industry Specialist - Green Buildings osaberi@ifc.org

Join the Conversation