Aerial view of Beira, Mozambique after the impact from cyclone Idai, May 3, 2019

Aerial view of Beira, Mozambique after the impact from cyclone Idai, May 3, 2019

Vanuatu, a South Pacific Ocean nation of roughly 80 islands, loses more than 6% of its GDP every year to natural disasters—a figure projected to increase with climate change. More frequent and intense natural disasters and rising sea levels threaten many of Vanuatu’s coastal resorts and infrastructure, severely affecting the country’s tourism sector, which accounts for about 20 percent of GDP. The economic impact of climate change, in turn, makes it hard for Vanuatu to invest in climate-change adaptation measures—which would be essential to enhance the resilience of its economy to natural disasters.

Vanuatu is not the only country simultaneously facing risks related to climate change and macro-financial vulnerabilities, limiting their ability to act and to make the transition to a climate-resilient, low-carbon economy possible.

There are, in fact, a significant number of nations facing the same dilemma. Our working paper, Macro-Financial Aspects of Climate Change, explains how high public-sector and financial-sector vulnerabilities constrain countries’ capacity to mobilize financing to prepare for and respond to the impacts of climate change. As natural disasters become more frequent, these countries face a higher risk of prolonged crisis and hardship.

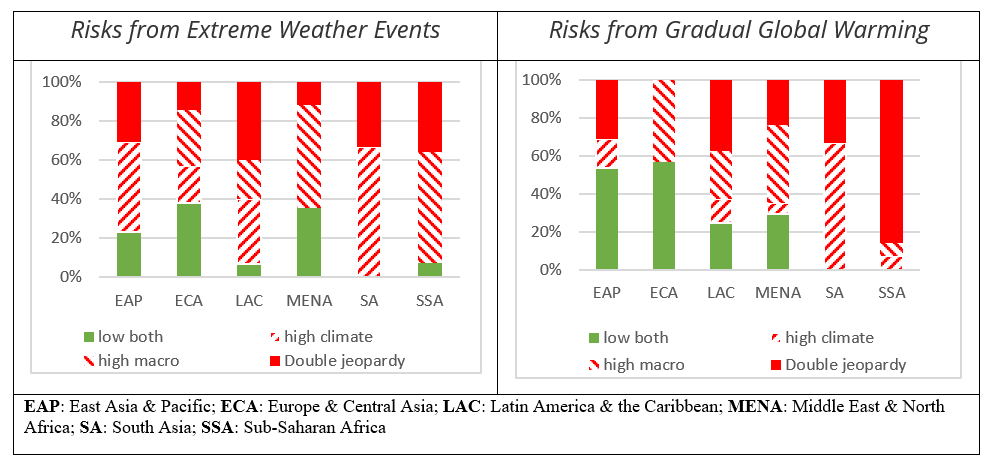

"About a third of countries in East Asia and the Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa are in 'double jeopardy' of elevated risks from extreme weather—such as floods, storms, and droughts—and from macro, debt, and banking-sector risks."

About a third of countries in East Asia and the Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa are in “double jeopardy” of elevated risks from extreme weather—such as floods, storms, and droughts—and from macro, debt, and banking-sector risks. In these countries, capacity to recover from physical damages caused by extreme weather events is limited. They face difficulty mobilizing enough resources quickly given pre-existing macro-financial risks such as those associated with elevated sovereign or private-sector debt levels – which can tighten funding conditions significantly in terms of, for example, availability of finance and pricing. With respect to rising temperatures, sub-Saharan Africa is the most affected by double jeopardy, which leaves the region in a weak position to confront climate vulnerabilities.

Climate change mitigation and adaptation require strong public and private balance sheets. High public-sector debt levels imply limited headroom for a fiscal response to a natural disaster—or to other shocks such as a pandemic that sharply affects tourism and other critical parts of the economy. A financial sector with elevated levels of non-performing assets will be in a weakened position to absorb agricultural loan defaults in the wake of a severe drought. Similarly, these risks could impede the flow of finance to green financial instruments, such as green bonds, and slow down the transition to a low-carbon economy.

To build resilience, reforms and international support are needed.

Country-specific reforms need be at the core of building macro-financial resilience and capacity to deal with climate-related risks. But because there seems to be a positive correlation between macro-financial and climate-related risks, support from the international community is also important. Based on our analysis, government policies should aim to:

- Strengthen macro-financial resilience. As the public and financial sectors play central roles in climate mitigation and adaptation efforts, measures to strengthen macro-financial systems are key for tackling the consequences of climate change.

- Assess and disclose climate-related risks. The analysis shows that climate change poses significant risks for the public and financial sectors. Efforts to assess these risks are still in their infancy. Data gaps should be addressed, and risks should be transparently disclosed and incorporated into monitoring exercises, including macro-economic and financial stress tests.

- Promote green finance. In addition to enhanced disclosure, green finance requires the development of widely recognized taxonomies, regulatory frameworks, and national strategies. This will incentivize stakeholders to incorporate climate issues into their risk management and investment approaches, as well as new financing instruments.

- Incorporate impacts of climate change in growth diagnostics. Climate change-related risks to economic growth are significantly underestimated. Well-designed adaptation and mitigation efforts may have positive impacts on growth. This points to the importance of reflecting climate-related risks and mitigation and adaptation impacts in the assessment of countries’ growth prospects and the design of growth strategies.

As natural disasters and other climate change impacts become more pronounced, it is important for policymakers and the international community to better recognize the tight inter-linkages between macro-financial and climate risks. Country-specific reforms will be at the core of building macro-financial resilience and capacity to deal with climate-related risks. However, there may also be need for the international community to consider strengthening the macro‐financial resilience and capacity of the most exposed countries as an element of international efforts to tackle climate change.

Join the Conversation