While great strides in poverty reduction have taken place in Colombia in the last decade, the number of people living below the poverty line increased by 6.8 percentage points since the start of the pandemic, reversing a decade of economic and social gains. Emergency social protection efforts, which included expanding social assistance programs and facilitating access to education and health services, prevented this increase from becoming even larger, with estimates suggesting that social transfers mitigated what could have been an additional 3.6 percentage point increase in poverty rates.

Even before the pandemic, social protection has played an important role in reducing poverty and inequality in Colombia. During the Covid-19 crisis, social protection has played a key role in mitigating some of the socioeconomic damage at a national level. But significant improvement at the national level can hide important differences within the country. Understanding the differences in experiences of vulnerable populations - including those affected by other shocks before the pandemic - requires an evidence-based approach. The findings of our upcoming study reveals differences in social protection coverage between host communities, those who were forcibly internally displaced (IDPs) by armed conflict within Colombia - a country with a long history of internal displacement -- and Venezuelans who migrated to Colombia due to the political and socioeconomic crisis in their home country.

Using a mixed methods approach, we collected quantitative and qualitative data in Bogotá and Cúcuta - two cities with a large share of displaced populations - to better understand the needs of people belonging to host communities and the two types of displaced groups and to explore how Colombia’s social protection system may more effectively respond to these needs. Our research is based on a 1,500-household survey conducted in early 2021 in low-income city blocks, equally distributed between host (511 households), internally displaced (512 households), and Venezuelan households (509 households). Below is a glimpse of some of our preliminary findings.

Access to social assistance: cash and in-kind

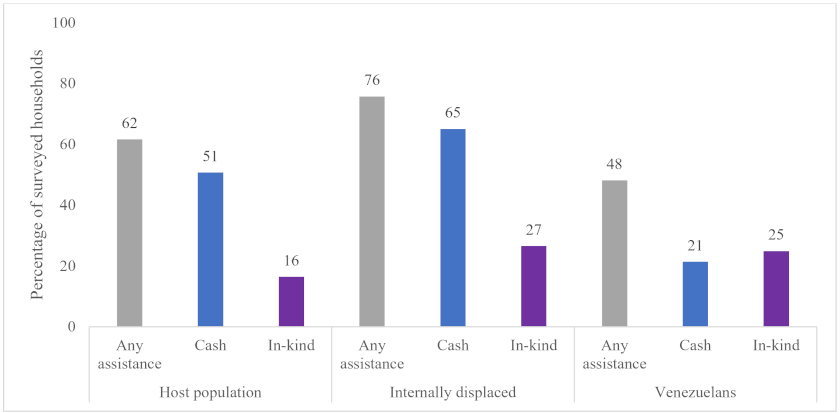

Our data indicates that a large share of all groups are currently receiving either cash or in-kind assistance. Among the three population groups, we observe differences in the number of households receiving assistance in some form of cash or in-kind programs. We find that 51% of all host households and 65% of internally displaced households are receiving cash, while only one in five surveyed Venezuelan households in low income areas - 21% - receive cash transfers. In-kind assistance is more prevalent among IDPs and Venezuelan migrants than in host communities.

Figure 1. Percentage of households receiving cash and in-kind assistance in Colombia

Access to basic services

Comprehensive social protection involves more than just receiving cash or in-kind assistance. We take a holistic view in our research by also considering access to basic services such as health and education. Providing adequate coverage of these services is critical for protecting human capital and promoting social mobility, particularly during a pandemic.

Our findings show several marked differences across groups:

- Despite the comprehensive coverage of Colombia’s health care system (over 86% of hosts and IDPs are covered by the national health insurance system), only 25% of Venezuelan migrants have health coverage. This reveals an important gap between hosts and Venezuelans, which may exacerbate the adverse effects of the pandemic on those who are unable to access care.

- Health insurance coverage does not always coincide with receiving medical care. Regardless of their coverage status, 87% of hosts, 90% of IDPs, and 77% of Venezuelan migrants responded that they received medical attention when they requested it.

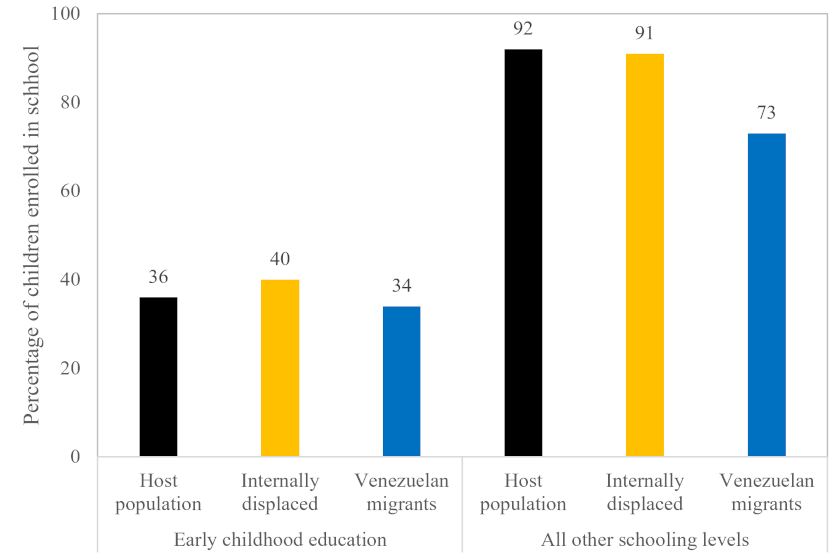

- Early childhood education (ECE) program enrollment is lowest among Venezuelan households with children under 5. The proportion is slightly higher for hosts and IDP households.

- School enrollment is far from universal, as only 73% of households with Venezuelan migrants having some or all children enrolled. Host households (92%) and IDP households (91%) have almost of their children enrolled in school.

In February 2021 when the survey was carried out, most children had not attended school in-person since closures began in March 2020 due to the pandemic. This is expected to lead to greater dropout rates and long- term learning costs (World Bank, 2021).

Figure 2. Children enrolled in school

Reducing inequalities in access to basic services is a vital complement to protecting vulnerable groups through social assistance programs, including cash and in-kind interventions. Addressing gaps in service access for displaced and vulnerable local populations is a priority because limiting access to adequate health and education can quickly translate into poverty traps and further deepening inequalities in well-being.

Social cohesion

In addition to examining the specific needs of each group, our study also looks at the interaction between them. In a country with internally and internationally displaced populations, social cohesion is key to ensuring adequate integration. Our survey found that one out of every two adults felt that the relationships between host population and displaced individuals are good. This perception, however, varies between Colombians and Venezuelans. More than 2/3 of Venezuelans agree that the host population gets along well with displaced people (either Venezuelan migrants or IDPs), but just over one-third of the host population and IDPs felt that Venezuelans and Colombians get along well. Despite generally having a positive view of their relations with the host community, we find that a higher share of migrants report experiencing discrimination than IDPs. They are also more likely to report difficulties in accessing job opportunities and for public services than IDPs.

Our research also explores the correlation between access to social protection programs and social cohesion using regressions that control for several demographic and socioeconomic factors. Perceptions of social cohesion is in general similar among the three groups, regardless of whether they receive assistance or not. But there may be differences between beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries in relation to different aspects of social cohesion, which we explore further in our forthcoming publication.

A comprehensive report on this research - including the role of social protection in meeting basic needs and promoting well-being among forcibly displaced populations - will be available later in 2021.

This work is part of a joint research program between the ODI and researchers from the School of Government at Universidad de los Andes to study how social protection coverage differs between vulnerable hosts and forcibly displaced populations in Colombia. It is also part of the program "Building the Evidence on Forced Displacement: A Multi-Stakeholder Partnership''. The program is funded by UK aid from the United Kingdom's Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO). It is managed by the World Bank Group (WBG) and was established in partnership with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). More information on the project can be found here.

Join the Conversation