truck carrying migrants

truck carrying migrants

In public debates, return is often regarded as the most natural solution for refugees: they are “out of place” and return seems the most sensible way to restore the natural order of things. But is it that simple?

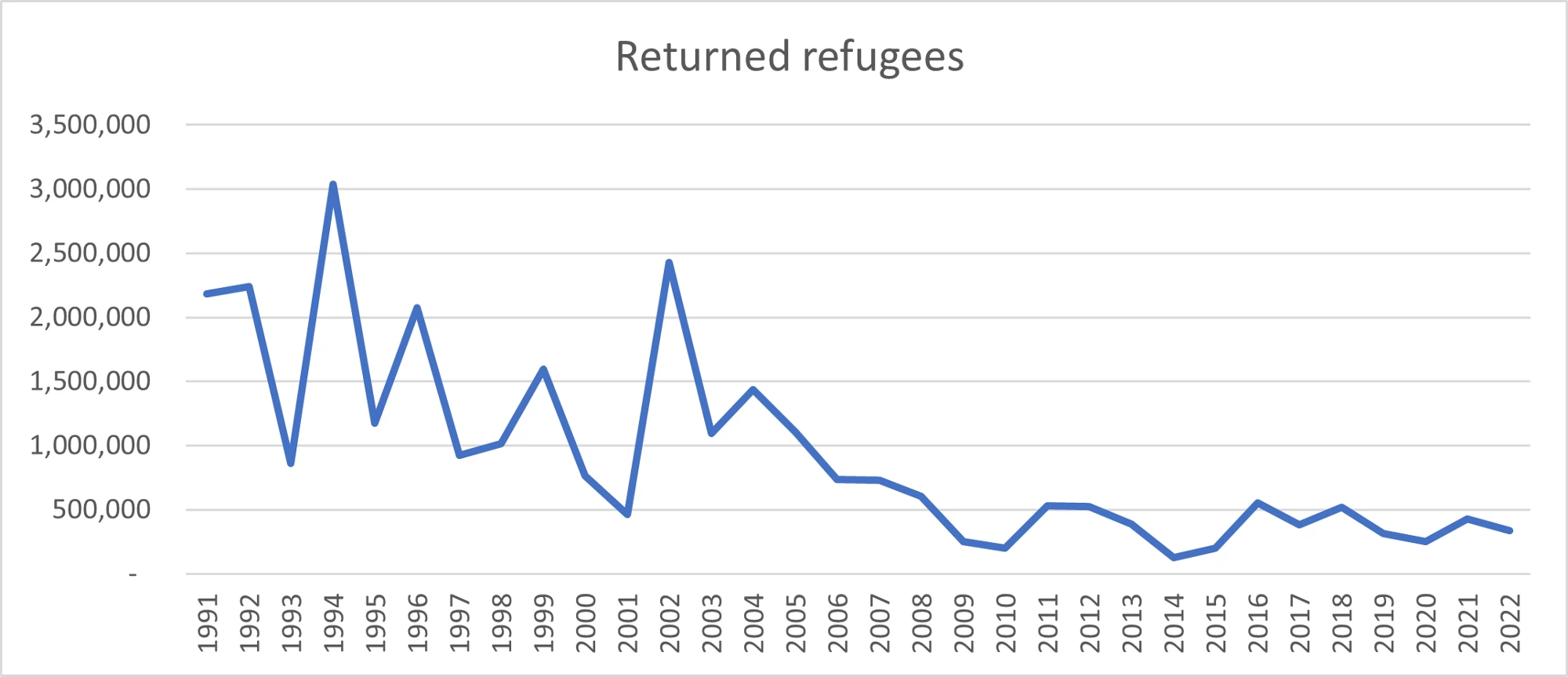

In every large-scale refugee situation, some return, others do not. From the end of the Cold War in 1991 to 2022 about 30 million refugees returned to their countries of origin, with the pace of returns slowing down over time (Figure 1). Four situations account for over two-thirds of these returns — Afghanistan following the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989 and the collapse of the Taliban regime in 2001; Rwanda immediately after the 1994 genocide and following the entry of Rwandan troops in Zaire; Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War; and Mozambique after peace was concluded in the early 1990s. Refugee returns tend to happen in peaks, typically about one to three years after the end of a conflict; past this period the pace of returns is much slower.

That refugees want to return is sometimes taken as a given, and their motivation for repatriating is assumed. Voluntary repatriation is often discussed in terms of a return “home” even a generation or more after the flight from conflict. And even when the descendants of the original refugees may never have seen their “homeland” or when the place of origin, affected by conflict and violence, has undergone wrenching social, economic, and political changes. In fact, voluntary repatriation is not a simple return to the preexisting order of things, but rather a new movement. It is not about reentering a condition that existed in the past, but rather about taking part in the emergence of a new social fabric and a new social contract in a post-conflict environment.

Return is hence a challenging process — and it is not always successful. Many returnees remain destitute or settle in unfamiliar parts of their country of origin, often as internally displaced persons (IDPs). Each wave of returns from Pakistan to Afghanistan has been followed by the expansion of informal settlements and slums around Kabul. Large numbers of failed returns can also add to destabilizing pressures in the country of origin when peace is fragile — of the 15 largest episodes of return since 1991, about one-third were followed by a new round of fighting within a couple of years — as repeatedly happened in South Sudan.

For hosting countries and their international partners, a new way of thinking is needed, one that focuses not only on refugee returns but also on the success of such returns. Indeed, failed returns create significant challenges for host countries. Many failing returnees go back to the country of asylum within a few years, creating renewed burdens for host communities. In fact, such back-and-forth cross-border movements, a succession of exiles and returns, are so common that the total number of returnees over time typically exceeds the peak number of refugees by about 30 percent. And when countries of origin are destabilized and experience renewed violence, new refugee outflows ensue.

What makes return successful?

The conditions in the country of origin are obviously critical, especially security and economic opportunities. But experience also confirms common sense intuitions refugees who make sustainable returns are those who return with a modicum of skills, financial resources, and social networks — in other words, those who have had an opportunity to get an education and to work while they were in exile. Refugees who were aid-dependent for years, or even decades, find many of the same difficulties as long-term unemployed people do when rejoining the labor force, and they often fail.

There has been a debate on whether the harsh treatment of refugees by host countries is likely to accelerate their return, in fact, it undermines the sustainability of such returns. What is good for refugees, being able to go to school, to work, and to earn a living, is also good for host countries that would like to see refugees return to, and stay in, their country of origin. For host countries and international partners, this implies a renewed focus on economic inclusion while refugees are in exile so that they have the opportunity to get an education and a job. This is critical to help refugees prepare for an eventual repatriation and a successful one.

Join the Conversation