The following post is a part of a series that discusses 'mind and mindsets,' the theme of the World Bank’s upcoming World Development Report 2015. Most children in Ethiopia and the other developing countries in the Young Lives Survey say they want—and expect—to go to college even though few of them will. Could those dreams differ by gender?

Most children in Ethiopia and the other developing countries in the Young Lives Survey say they want—and expect—to go to college even though few of them will. Could those dreams differ by gender?

Before we look at the data, who would you predict are more likely to have college hopes: boys or girls? As advocates for gender equality, we would like to find no difference. But then again, there is a reason we need to be advocates for gender equality.

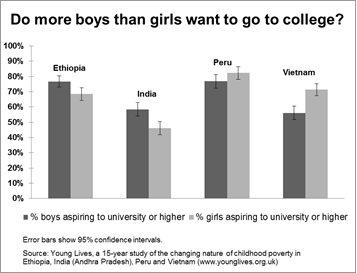

So which is it: do boys have higher aspirations, or do girls? The answer is, both. It is boys in Ethiopia (77% vs. 68%) and India (58% vs. 46%), as indicated in the chart showing the percentages of college aspirants by gender. But it is girls in Peru (77% vs. 82%) and Vietnam (56% vs. 71%). The likelihood that the differences are due to chance is less than 5% for each country except Peru.

It could just be the way I sliced the data. Put all four countries together and you find no meaningful difference whatsoever: 66% of boys and 65% of girls want to go to college. When the same data can so easily support opposing claims, we need to be very careful about what we say.

Suppose the gaps reflect real social influences that differ across gender and that differ across countries. With the information we have so far, we cannot know what is causing kids to dream differently in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam. But the 2015 World Development Report suggests a good place to look might be the shared beliefs about gender in each community. Often such beliefs can be so ingrained that we accept them as facts of nature instead of the products of society they are. Quick quiz: is it men or women who paint their nails?

When the norm in our community is that sons go to school but daughters aren’t worth it, we educate our sons and keep our daughters back at home. If we were to meet a successful, educated woman, we might reconsider that belief and reconsider our choices, but so long as we never send our girls to school we never get to know Ms. Contradictory Evidence. The status quo sustains itself.

Beliefs like that can filter down to our children and shape what they see as the opportunities available to them and the futures worth striving for. Since the Young Lives researchers interviewed not only children but also their parents, as a next step we can actually look into whether adults in those communities have different educational aspirations for their sons and their daughters. One such study using the Young Lives data found that gender gaps in parental aspirations for their kids at age 8 became gender gaps in the aspirations of the kids themselves at age 12, which corresponded to gender gaps in performance on cognitive tests at age 15. I will report more on the Young Lives parents in a future post.

Incidentally, earlier I touched upon a second topic from the 2015 World Development Report: the effect of framing. Which result sounds more compelling: there is a 5% chance that boys and girls have equal aspirations, or there is a 95% chance that dreams do differ by gender? The way we frame equivalent information can alter the way that people respond—a behavioral insight that policymakers (all of us, really) should be mindful of when deciding how to communicate their messages.

Join the Conversation