IT’S robots that mostly come to mind when you ask people about the future of work. Robots taking our jobs, to be specific. And it’s a reaction that’s two centuries old, in a replay of Lancashire weavers attacking looms and stocking frames at the start of the first Industrial Revolution. A secondary reaction, among a much smaller group, is the creation of new jobs in the coming fourth Industrial Revolution.

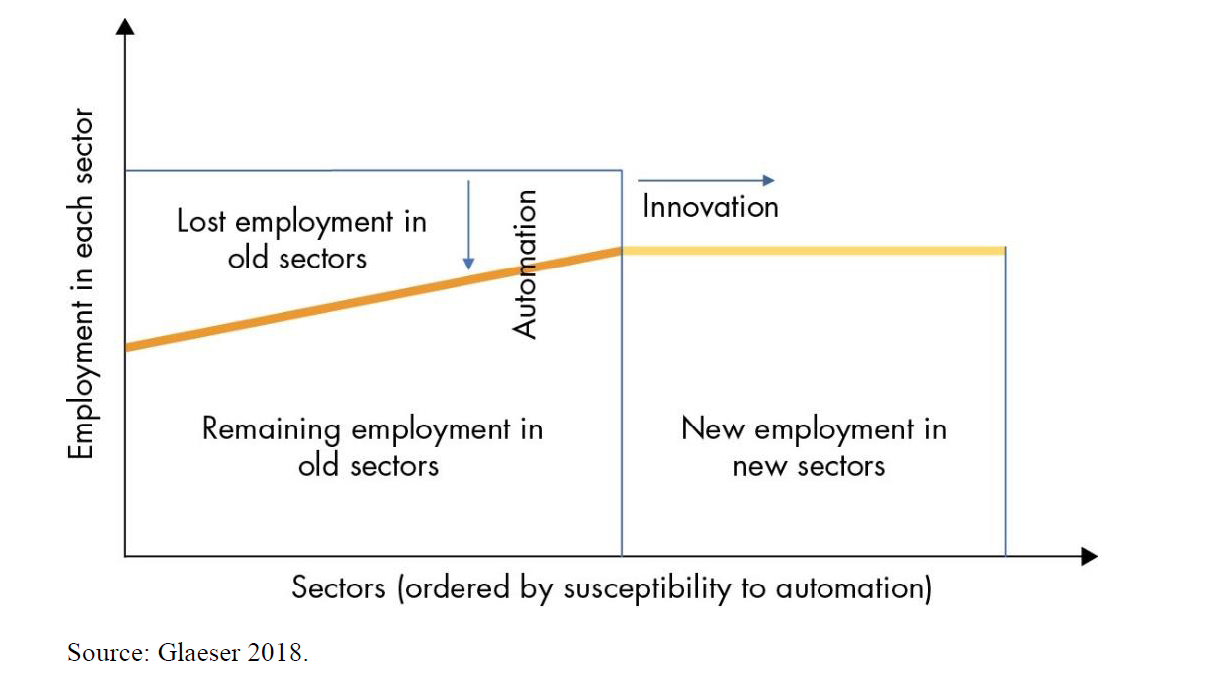

Professor Ed Glaeser at Harvard neatly summarizes this dichotomy in one figure:

On the left side are old industries, where some workers are being replaced by robots. This change is animating research and policy discussions in the United States and Europe. On the right are jobs in new sectors arising from innovation. In emerging markets like India or China these jobs easily outpace the jobs which are and will be lost as a result of automation. In these countries, creating the next new sector is the craze.

But automation and innovation manifest themselves in other ways too. One of the more exciting directions for economic research is the changing nature of firms. The WDR2019 (http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2019) sets out some of the features of what’s happening: physical assets become a thing of the past (think of Yandex, the Russian share-ride company); the boundaries of the firm blur as start-ups quickly become global players by selling online (think of China’s Alibaba); consumer data are explored to open new markets (think JD Finance, China’s most innovative small business creditor).

These changes bring challenges too – and one of them is corporate governance. I single it out because I recently attended a conference on corporate governance at the Dutch Central Bank. Stijn Claessens, a mentor to me when he worked for the World Bank, was the host.

Let me list some of the ways in which new economy firms (often described as ‘platforms’) differ from traditional firms in corporate governance terms. First, their founders are typically both the CEO and the largest shareholder - and even the company’s marketing face (Jack Ma at Alibaba springs to mind). Company valuations are based to a large extent on their public personae. They often sport dual-class shares, further cementing the founders’ hold on decisions.

Second, platform companies typically tap money on private markets, using neither banks nor public capital until well into their growth binge. Many of these companies generate cash flows that are sufficient to fuel expansion without the need of creditors.

Third, employees are typically the second-largest shareholder bloc. But as their company shares get vested after a period of time, these employees are beholden to the founders’ vision. And, as a result, they do not provide an independent voice.

So what happens is that decision-making in platform companies is highly concentrated and transitional governance mechanisms are wanting. This is fine as long as outside investors’ money is not at risk. But when platform firms go public, risks abound.

The main risk comes from regulation. In most new economy sectors, regulation is scant to non-existent. Ant Financial, the financial arm of Alibaba, does not have a banking license. Yet its activities increasingly look like banking. If and when the regulator decides to step in, shareholders will face a different (and less positive) value proposition.

The second risk comes from changing tax policies. In most emerging economies (and in advanced economies too, as a matter of fact) platform companies’ profits are barely taxed. This is about to change, as a result of pressure from other sectors and governments’ needs to create fiscal space for more social protection. Again, valuations are likely to be affected. But that’s in the future.

For other risks and rewards, you can read more on this in chapter 6 of the #WDR2019 (http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2019).

Join the Conversation