Photo: World Bank / Henitsoa Rafalia

Photo: World Bank / Henitsoa Rafalia

The COVID-19 pandemic was a shock to the global economy like no other since the Great Depression, with major impacts on the public finances of rich and poor countries alike. Since then, more than $16.9 trillion of fiscal support measures have been implemented worldwide to reinforce healthcare systems and support households and businesses. This support has helped to contain the impact of the crisis, but the resulting fiscal deficits and rising debt levels will hamper policy makers’ choices for years to come. The war in Ukraine has further intensified the pressure—through its global effects on growth, trade, and food and energy prices.

Fiscal tightening will certainly be needed in nearly all countries to stabilize their public debt ratios. A World Bank report suggests that in many countries policy makers’ ability to do this may be restrained by budget rigidities that predated COVID and might have only intensified since. This is especially worrying because these rigidities may force governments to cut more discretionary components of spending, such as public investment, which can significantly reduce long-run growth.

Budget rigidities are institutional, legal, contractual, or other constraints that limit the ability of governments to change the size and composition of the public budget, at least in the short term. They originate, among other things, from demographic factors such as an aging population and rules that predetermine the level of certain types of expenditure. Policy makers often complain about budget rigidities, yet the topic has been largely ignored, mostly because of a lack of measurement tools that would allow cross-country comparisons . That deficiency has affected policy-making performance.

Aiming to address this inadequacy, the World Bank analysis constructs a new measure of spending rigidity that can be applied to a large set of countries across time.

The report found significant differences across regions (figure 1). In the area of public sector payrolls, South Asia (SA) and Europe and Central Asia (ECA) had seen a declining trend before COVID-19; Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) showed remarkable stability; and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), East Asia and Pacific (EAP), and Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) showed significant increases. Pensions show a rising trend—especially in ECA and LAC—that is projected to continue for several decades. Interest payments increased in almost all regions (with the exception of South Asia) prior to COVID-19, especially because of higher debt levels.

Figure 1. Budget rigidity sources across the world over time

Source: Herrera and Olaberria (2020).

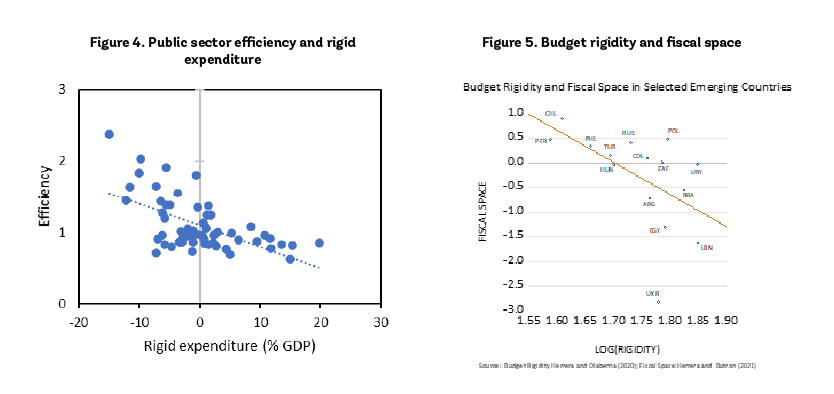

Countries with higher budget rigidity tend to spend more (figure 2) and have higher tax rates (figure 3). Budget rigidity is also associated with lower efficiency of public spending (figure 4) and reduced fiscal space (figure 5). If budget rigidities are perceived to prevent the government from reducing budget deficits, financial markets will downgrade the government’s quality rating as a borrower, which would increase a government’s financing costs.

COVID-19, along with the war in Ukraine, is likely to lead to higher budget rigidity amid higher debt levels and increased spending. Higher debt and debt-servicing costs have already constrained the COVID-19 fiscal responses of developing countries, where tax cuts and spending increases have been relatively modest . The ratio of public debt to GDP, which increased sharply in 2020 because of the crisis, has stabilized in 2021, but in the coming years it is expected to remain persistently higher than the levels projected before the pandemic, constraining governments’ ability to consolidate fiscal deficits and stabilize debts.

Source: Herrera and Olaberria (2020),

| Source: Herrera and Olaberria (2020). | Source: Authors’ calculations based on Herrera and Olaberria (2019), Kose et al. (2017), and Herrera and Butron (2021). |

Reducing budget rigidities would help policy makers address fiscal imbalances and make fiscal policy more effective. An effective strategy would involve:

- Increasing the retirement age and facilitating private sector participation in the pension funds sector.

- Ensuring that medium-term fiscal planning incorporates the costs of any wage increases or any support required to buffer future pension payments.

- Delegating decisions on long-term budget composition to technical fiscal councils, such as the wage bill or allowance for early pension withdrawals (which were ubiquitous during the COVID crisis).

- Increasing budget transparency to reduce the need for spending floors or spending rules and ensure allocation of resources to the most cost-effective activities.

- Reducing budget fragmentation, given that the complete picture of public-resource allocation and distribution allows for a more expedient budget approval process as circumstances evolve.

- Limiting earmarking and introducing exit clauses to existing constitutional spending mandates.

Finally, governments should resist the temptation to evade rigidities by exploiting highly distortionary taxes or reducing public investment. Instead, they should seize the opportunity to address rigidities head-on and to modernize tax systems and broaden tax bases. This may be the right moment to introduce and expand ‘green’ and property taxes. Governments can also reduce tax expenditures, particularly exemptions and lower rates of value-added tax, which reduce much-needed contributions from the well-off. Such reforms would not directly eliminate budget rigidities, but they would increase revenue and improve the efficiency of the tax system, while also raising fiscal space for development spending.

Join the Conversation