A scene in the Amazon region of Brazil, near Manaus. Here locals harvest mandioca, coconuts and cocoa and other freely found goods to eat and to sell. Brazil. | © Julio Pantoja / World Bank

A scene in the Amazon region of Brazil, near Manaus. Here locals harvest mandioca, coconuts and cocoa and other freely found goods to eat and to sell. Brazil. | © Julio Pantoja / World Bank

Deforestation, including in the Amazon, remains a major problem in Brazil. Rising global demand for food and lax enforcement of environmental protection laws in past years—which the Brazilian government is now aiming to reverse—have been contributing to it. Deforestation is intrinsically linked to an extractive growth model that pushes the agricultural frontier ever deeper into virgin forests. Is the issue, then, that agriculture is expanding into the Amazon (extensive agriculture) rather than using existing land more productively (intensive agriculture)?

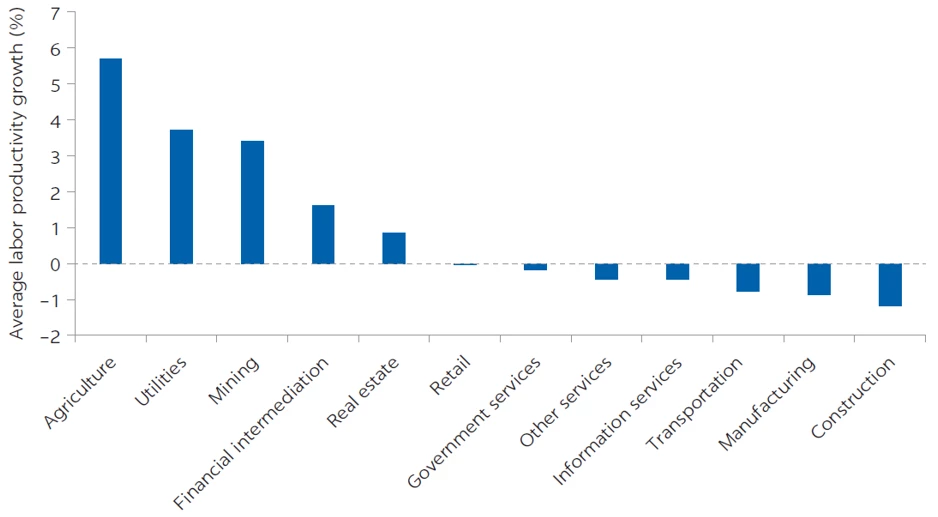

In principle, yes. If a given amount of agricultural demand requires fewer resources—the very definition of productivity—then less land is used, limiting incentives to convert natural forests into agricultural land . Research shows that, globally, raising agricultural productivity reduces deforestation. In Brazil, labor productivity growth in agriculture has grown faster than in all other sectors over the last 25 years (figure 1).

Figure 1: Labor productivity growth in Brazil, by sector, 1996-2021

Source: World Bank, using data from the Regis Bonelli Productivity Observatory database, Brazilian Institute of Economics (IBRE) of Fundação Getulio Vargas (FGV IBRE).

But does this mean that promoting agricultural productivity will save the Amazon? Here things get more complicated.

Jevons’ paradox

In the 1800s, British economist William Stanley Jevons studied energy consumption and found that, paradoxically, technology promoting productivity in coal actually increased coal consumption. The reason is intuitive: relatively cheaper and more efficient coal will attract more consumers away from other energy sources. The theory can be applied to agriculture in the Amazon: raising productivity will allow farmers to sell more, taking market share from producers elsewhere. Whether this causes more or less deforestation depends on many factors, including the land market. Deforestation will be more likely if it is cheaper to increase production using more land relative to labor, capital, or inputs, like fertilizer .

If land is the cheaper option, then Jevons’ paradox applies, and higher productivity increases demand for land and therefore deforestation—despite agriculture becoming more efficient. In this case, agricultural productivity would not save the Amazon, even if it could reduce pressure on natural forests in other parts of the world which lose market share to Amazonian producers.

It remains unclear whether Jevons’ paradox holds for agriculture in the entire Amazon. But focusing on Brazil’s Amazon states—Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Mato Grosso, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima, Tocantins, and parts of Maranhão— our research, in the World Bank’s recent Amazon Economic Memorandum and in line with other recent empirical research, suggests that it does. This is further corroborated by anecdotal evidence: farmers benefiting from publicly-funded productivity support were violating environmental laws to deforest their properties later.

Containing Jevons

Our recent research shows that mitigating Jevons’ paradox requires a mix of policy actions:

Command and control. Most deforestation in Brazil is illegal thanks to its landmark Forest Code. In principle, enforcing the code—through command and control interventions—would restrict the amount of natural land available for agricultural conversion. Using more land would no longer be the cheapest way to grow agricultural output, since it is now scarcer, encouraging agricultural intensification.

Yet the implicit increase in production costs is unpopular with producers and consumers, making it politically more difficult to enforce, especially across a large land area with relatively weak institutions. This can undermine the effectiveness and sustainability of command and control interventions.

Fortunately, complementary policies can provide further support:

- Performance-based finance. Conservation finance could provide strong incentives to protect Brazil’s natural forests, especially if payments are conditional on proven performance . Brazil already has some experience with performance-based financing, including the Amazon Fund. Sustainability-linked bonds are another performance-based financing tool Brazil could pursue.

- Growth beyond the Amazon states. These states account for less than a fifth of Brazilian agriculture—Mato Grosso alone accounts for almost a third of Legal Amazon output). Our research suggests that raising productivity in areas outside the Legal Amazon would also alleviate deforestation. This is because productivity gains would mostly occur in markets where deforestation happened long ago, and agricultural markets are more mature. As extensive agriculture is less feasible, productivity gains would result in agricultural intensification, taking pressure off natural lands in the Amazon, and other forests across the world.

- Diversification across Brazil. Although Brazil’s excessive specialization in commodities causes deforestation, this could be reversed by overcoming the legacy of import substitution industrialization and trade protection of Brazil’s non-commodity sectors. Our research shows that boosting productivity in manufacturing and related services is a winning strategy both for the Amazonian states and the whole country—and if coupled with more agricultural productivity, overall output can grow with much less damage to forests. Although reversing the long-term decline of manufacturing and certain services (figure 1) could yield big gains, it will not be easy.

A balancing act for policy

Finding the right policy mix to maximize socioeconomic development and minimize environmental damage is challenging. The more complex the challenge, the more instruments are needed to address it. Policy should strengthen agricultural productivity but remain mindful of the potential unintended consequences for natural forests. Stronger institutions, together with more mature and diversified markets, will make it more likely that agriculture and forests can exist in harmony.

Join the Conversation