A backgroun of coins, compass, and charts. | © shutterstock.com

A backgroun of coins, compass, and charts. | © shutterstock.com

Harmful tax competition in East Asia and the Pacific (EAP) has intensified in recent years, with many developing countries in the region using tax incentives as a key tool to attract foreign direct investment (FDI). While advanced EAP economies such as Australia, Japan, Hong Kong SAR, China, and New Zealand offer few incentives, developing EAP economies offer a broad range, including blunt instruments such as tax holidays and reduced tax rates, with costly revenue implications. East Asia and Pacific, Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America and Caribbean regions have the highest frequency of countries offering tax holidays.

Tax incentives — important but not critical to investment decisions

The quest to attract FDI is understandable. But research and surveys consistently show that firms do not rank tax incentives as the primary reason for choosing where to invest. Instead, political and macroeconomic stability, the legal environment, and labor skills are the key determinants of FDI, according to the World Bank Global Investment Competitiveness Report 2020.

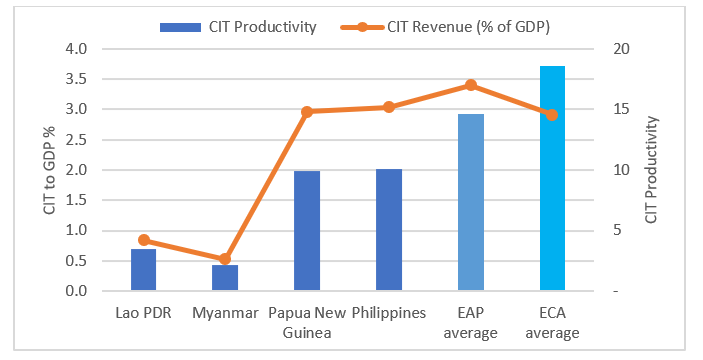

In EAP, competition for FDI triumphs over efforts to rationalize tax incentives, leading to sizable revenue losses. For example, in the Lao PDR, the World Bank’s forthcoming PER report (2023) indicates that the corporate income tax (CIT) gap – the difference between taxes legally owed and those collected – was over 80% in 2020. In practice, tax competition leads to a ‘race to the bottom’, with large investors able to play off one country against another to reach favorable deals that involve long tax holidays. This has led to increased tax incentives in recent years in a number of EAP countries. Notably, Cambodia, Indonesia, Fiji, Lao PDR, Myanmar, and Papua New Guinea have ramped up their tax incentives offering. As a result, CIT productivity, defined as the ratio between the actual CIT collection as a share of GDP and the standard statutory rate, in the region is low. As a high-level, composite indicator, CIT productivity reflects the efficiency of the overall CIT system and is, inter alia, highly sensitive to blunt profit-based incentives such as tax holidays and rate cuts. In 2019, the CIT productivity hovered around 10 percent or less in Lao PDR, Myanmar, the Philippines, and Papua New Guinea—significantly lower than averages observed in EAP overall (14.6%) or in Europe and Central Asia (18.6%).

CIT productivity ratio (2019)

Source: World Bank staff calculations using data from IMF FAD, PwC, OECD (Japan), and authorities

Excessive tax incentives undermine the fairness and efficiency of the tax system and reduce the government’s capacity to finance growth-enhancing investment in infrastructure and human capital . This is particularly acute in developing East Asia where the average tax to GDP ratio is 13.1 percent, significantly less than their aspirational high income peers who average around 17.6 percent.

Potential Benefits from Global Minimum Tax for Developing Countries

This situation could change next year when the Global Minimum Tax (GMT) comes into effect. In October 2021, the G20 introduced the global agreement on CIT that aims to achieve a global minimum effective tax rate of 15 percent for multinational enterprises (MNEs) with a global turnover above EUR 750 million. Although ambitious, the agreement is set to be implemented in 2024.

The GMT does not directly obligate countries to adopt a minimum CIT rate of 15 percent. However, the plan incentivizes countries to raise their effective CIT rate to the 15 percent minimum. Two sets of rules are applied. The first allows countries where the parent company of an MNE is taxable to impose a top-up tax on the profits of any foreign subsidiaries paying an effective tax rate of less than 15 percent. If the home country of the parent company chooses to impose a CIT rate of less than 15 percent, then the second rule allows the host country where the MNE subsidiary carries out its business activities to charge top-up taxes on the subsidiary.

Effectively, while countries are free to offer tax holidays and CIT rates below 15 percent, as GMT rules are coming into effect, they are giving away their taxing rights to the FDI exporting countries (rule #1) or countries where MNE subsidiaries operate (rule #2). At the same time, MNEs will no longer benefit from tax holidays and reduced rates, because there will always be one or several countries that will bring their effective tax rate to 15 percent.

Countries that do not act upon the GMT, especially developing countries with a wide range of tax incentives, could lose out when other countries introduce domestic tax rules to top up undertaxed profits. Several EAP countries, including Australia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, and New Zealand, are advancing implementation.

At a minimum, countries should evaluate the effective tax rate applicable to businesses operating in their jurisdictions that are subsidiaries of the MNEs that will be subject to the GMT. If there are cases where the effective CIT rate is below 15 percent, countries should consider introducing domestic top-up taxes to expand their tax base. In addition, countries should consider reforming their tax incentives to align with the GMT. Countries could go further by overhauling their CIT policy framework to be compatible with the GMT while making their CIT regime more attractive to investment, stimulating economic growth. (See the detailed GMT administrative guidance from OECD: OECD (2023), Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy – Administrative Guidance on the Global Anti-Base Erosion Model Rules (Pillar Two), OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD, Paris.)

The GMT provides an opportunity for developing EAP countries to raise much-needed domestic revenue as part of a coordinated global agreement to set a minimum corporate tax rate . EAP countries should embrace this opportunity and use the GMT global coordination as a springboard to overcoming harmful regional tax competition by committing to stronger regional coordination on tax matters.

Join the Conversation