Coronavirus vaccination program in Papua New Guinea. PX Media / Shutterstock.com

Coronavirus vaccination program in Papua New Guinea. PX Media / Shutterstock.com

Papua New Guinea (PNG) is, economically, one of the poorest countries in Asia-Pacific, with significant human development challenges. Its health infrastructure is run-down. Approximately 85% of the country live outside of the cities, and moving around the country is extremely difficult. Until relatively recently, the biggest impact of COVID-19 on the country had been economic. However, in recent months the Delta variant of the virus has taken off. Health services are being overwhelmed and, although data are patchy, reports suggest rapidly rising deaths.

COVID-19 vaccination rates are low in PNG; in fact, some of – if not, the – lowest in East Asia Pacific. Supply of vaccines was an issue at first, and issues with health infrastructure are an ongoing problem. But news reports, as well as a series of smaller studies, have pointed to vaccine hesitancy as a serious impediment to vaccination uptake too.

In late May 2021, our team began research to find out just how prevalent COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was in Papua New Guinea. We also sought to learn more about potential drivers of vaccine hesitancy, and how it might be reduced.

This research involved adding questions to an existing World Bank phone survey and conducting a separate online experiment. Both samples were large (2533 for the survey; 2392 for the experiment). However, neither cell-phone use, nor access to the internet are universal in Papua New Guinea. These facts posed a challenge; however, as we detail in our new World Bank discussion paper; the challenge wasn’t insurmountable. Weighting, drawing on the most recent Demographic and Health Survey and census, allowed us to produce findings that were more representative of the population. ‘Broadly representative’ is far from perfect, but in the middle of a pandemic, in a remote country where surveys are extremely difficult to deliver, our approach was the most feasible way of answering questions that are increasingly urgent.

The bad news from the phone survey is that vaccine hesitancy is high in Papua New Guinea. Less than one in five respondents who were aware a vaccine exists said they were planning to be vaccinated against Covid-19. These numbers indicate that PNG’s vaccine hesitancy is potentially some of the highest in East Asia Pacific; at least it was when the survey was conducted in May and June; before the current outbreak which has now claimed many hundreds of lives.

Responses to phone survey question (May/June 2021) on whether participant was planning to be vaccinated

In theory, people might simply have had practical reasons for not planning to be vaccinated, such as difficulty accessing vaccines. However, when our team asked participants why they weren’t willing to be vaccinated, by far the most common answers were to do with the vaccine: fear of side-effects, or distrust in it.

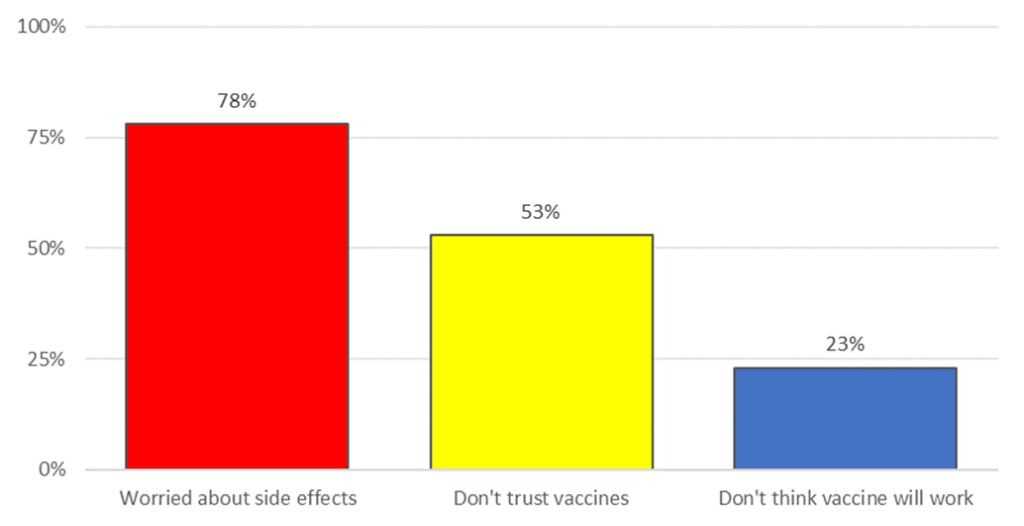

Responses to phone survey question about why participant was not planning to be vaccinated

Note: multiple responses were allowed to this question, hence percentages total to more than 100.

Although online misinformation has been an issue over the course of the pandemic in Papua New Guinea, survey results suggest participants’ vaccine hesitancy didn’t seem to be coming directly from the internet, with only a small proportion of respondents to the phone survey said they used the internet for health information. And there was no correlation between people’s trust in information from the internet and their willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Certainly, internet misinformation might still be affecting people’s views about vaccines indirectly in PNG, with rumours starting online before subsequently being propelled by word-of-mouth. But the internet on its own does not seem to be primary driver of vaccine aversion.

Respondents to the phone survey were, unquestionably, worried about the vaccine. Yet other responses suggested their views might possibly be changed. When respondents that did not plan on being vaccinated, or who were unsure, were asked what type of person, if anyone, might change their mind, many stated that they would listen to health professionals. In another question we asked respondents about their preferred means of receiving vaccine information; with more than 80 percent saying they preferred face to face communication with health workers.

People who could change respondents’ minds about getting the vaccine (phone survey)

Note: multiple responses were allowed to this question, hence percentages total to more than 100.

Results from the online survey experiment confirmed that people’s views about the vaccine could, indeed, be changed. In the survey experiment, participants were randomly allocated to either the control group, which received no information about COVID-19 vaccines, or three treatment groups, with each of the treatment groups receiving a simple sentence of information about COVID-19 vaccines.

- The first group were informed that ‘national and international experts’ considered the vaccines safe and effective (we’ll refer to this as the ‘experts message’).

- The second group were informed that many Papua New Guineans were getting vaccinated. This was an attempt to appeal to norms, and we’ll refer to it as the ‘norms message’.

- The third group – which we’ll refer to as the ‘relative safety message’ – were told that the vaccine was safe, whereas COVID-19 had killed people in PNG.

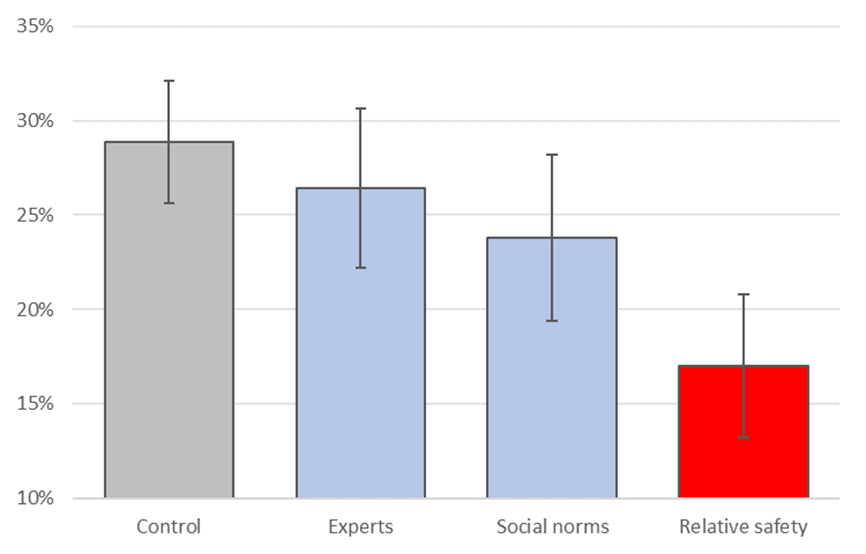

The effect of the treatments (using unweighted response data) is shown below.

Survey experiment results: share of respondents willing to be vaccinated

Survey experiment results: share of respondents not willing to be vaccinated

The ‘experts’ message was not effective in changing views. However, the ‘relative safety’ message clearly increased the share of respondents willing to be vaccinated and caused a substantial fall in the share of respondents who were unwilling to be vaccinated. What’s more, when we weighted responses, the effects of the ‘social norms’ message became statistically significant too.

Tackling vaccine hesitancy:

PNG faces an urgent task: it needs to quickly increase COVID-19 vaccination rates. Yet vaccine hesitancy is worryingly high. However, there is hope and opportunity: our research suggests many Papua New Guineans’ views are not set in stone. The hesitancy appears to be genuine hesitancy, rather than hardened ‘anti-vax’ attitudes. People are open to having their minds changed, and our research also points to the fact that vaccine hesitancy can be addressed successfully with the right messages and the right messengers. With clear information about vaccine safety, as well the dangers of COVID-19, communicated by local health workers, views can be changed; and ultimately, many lives can be saved.

Join the Conversation