Group of traditional indian women wearing colorful sari. | © Adobe Stock

Group of traditional indian women wearing colorful sari. | © Adobe Stock

Only recently, 22-year-old Sanjana committed suicide after repeated episodes of torture and harassment by her husband and his family over dowry-related disputes, and a man divorced his wife Saba and threatened to burn her alive after constantly abusing her over dowry and gifts demands. The effects of centuries of patriarchal norms that discriminate against women’s property rights are also evident in stories like K. Bina Devi and her sister, which due to the fear of disrupting the relationship with their families, gave up their share of the family property to the benefit of their four brothers in a family ceremony celebrating “haq tyaag.”

These stories underscore how social norms continue to exert a powerful influence on the lives of Indian women, even in the face of legislative efforts to address issues such as property rights and violence against women. While India has made significant strides in enacting laws to protect women, the effective implementation of these laws remains a challenge.

India has experienced immense economic growth since its independence in 1947, but women and men do not share this growth equally. Women's economic participation remains dismally low, with only 23.0 percent of women in the labor force in 2021, compared to 72.7 percent for men, resulting in a staggering gender gap of nearly 50 percentage points. According to the Women, Business and the Law 2023 report, women in India have only 74.4 percent of the economic rights of men. Up from 49.4 percent in 1970, reforms of inheritance laws and violence against women legislation stand out: they provide the foundations for women’s access to property and their safety which are the underpinnings of socioeconomic participation of all women.

The reform process for protecting women from violence took over 60 years and saw both the Supreme Court of India and a thriving civil society playing key roles. The brutal gang rape of social worker Bhanwari Devi in 1990, during her work to combat child marriage in a village in Rajasthan, triggered an urgent debate over the need for legal protections for women in employment. As a result, the Supreme Court of India issued the Vishaka Guidelines in 1997, which filled the void in statutory law until the government enacted the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act in 2013. However, the absence of guidelines, monitoring mechanisms, services, and budgetary allocations, are among the limiting factors to the full implementation of the law.

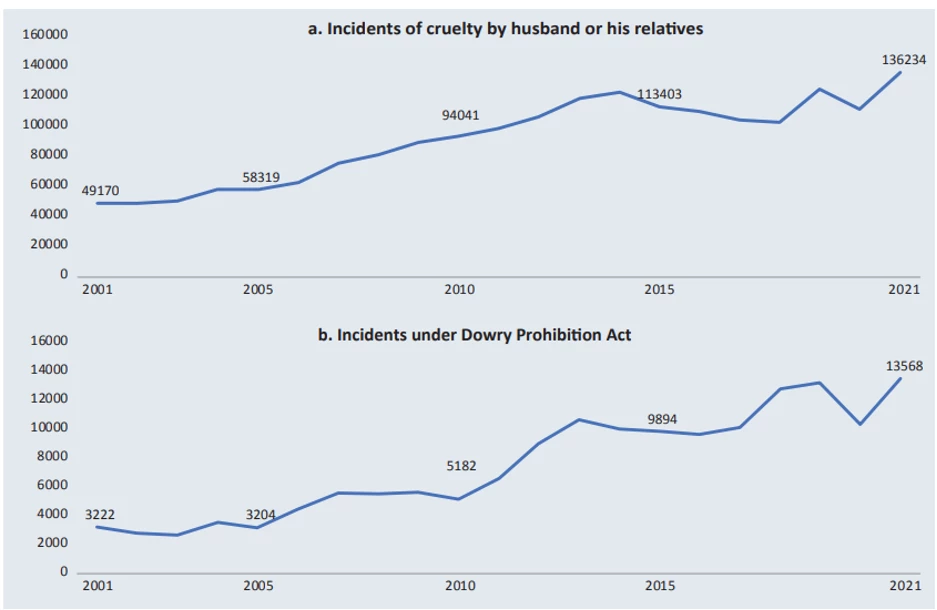

A similar decades-long journey led to the adoption of legislation on domestic violence, beginning with the Dowry Prohibition Act of 1961 and culminating in 2005 with the Domestic Violence Act. The shift from dowry-related violence only to a comprehensive definition of domestic violence was key. However, despite the laws’ prohibition of giving or receiving a dowry, criminalization of dowry-related violence, and of all forms of domestic violence, in 2021 alone, 6,589 dowry-related deaths were recorded, as well as 13,568 dowry-related incidents, and 136,243 incidents of cruelty by husbands or their relatives (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A Twenty-Year Sample of Crimes Against Women (2001 to 2021)

Source: 230th Report of the Parliamentary Standing Committee 2021; NCRB 2020,2021.

Dowry, a practice deeply rooted in Indian culture for centuries, has taken an alarming and extortionate turn, putting immense pressure on the bride's family, and resulting in violence and harassment. The practice has contributed to the perception of women as burdens and less valuable than men. However, its original intent was to provide voluntary gifts to daughters upon marriage for their enjoyment and financial security, a gesture intended to support women in a society with limited property rights for them.

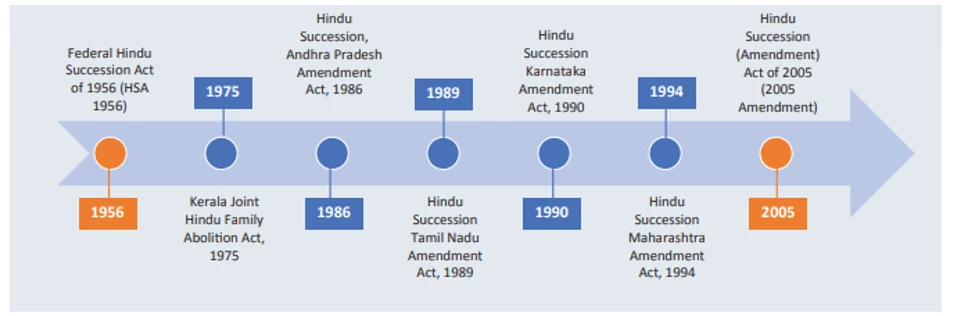

Access to property is vital for women's economic participation as entrepreneurs and employees. India’s Hindu Succession Act of 1956 initially denied women the right to inherit ancestral Hindu family property, reserving it for male family members only. Enacted shortly after independence, the Act aimed to codify and harmonize the various customary laws governing the Hindu community (a majority of the country’s heterogeneous society) across states. Over time, states began amending their laws to ensure equal inheritance rights for sons and daughters (see Figure 2). About 50 years after its enactment, following decades of negotiations, in 2005, the Hindu Succession Act was finally amended to secure Hindu women’s inheritance rights at the federal level. While this was considered a remarkable step forward, women across all communities (whether Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Parsi, or otherwise) continue to face challenges in law and practice when attempting to access and own property.

Figure 2. Timeline of the Federal Hindu Succession Act and State Amendments

Source: Women, Business and the Law database.

Continued legal reform, social norms interventions, and awareness campaigns are needed so that Indian women can fully claim their rights to live free from violence and be empowered economically. Our policy brief series: How Did India Successfully Reform Women’s Rights? - Part I: Answers from the Movement on Equal Inheritance Rights” and Part II: Answers from the Movement on Protection from Violence examines how the country has been working to overcome this divide and what important next steps should be on the agenda to allow women like Sanjana, Saba, and K. Bina to finally live their lives to the fullest.

This blog is part of a series focusing on reforms in seven economies, as documented by the Women, Business and the Law (WBL) team. Support for the work in India is provided by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Join the Conversation