Thinking about inequality is back in fashion! In its November 2013 outlook, the World Economic Forum called rising inequality the second biggest risk for 2014-15. The 2014 English translation of French economist Thomas Piketty’s “Capital in the 21st Century” became an instant bestseller among academics and practitioners in both developed and developing countries. Discussions of inequality are popping up everywhere, and even seem to be setting the tone of many round tables and presentations in the World Bank Group’s upcoming Annual Meetings.

Virtually all work on global inequality is based on compilations of household survey data, which as the work started by Piketty and co-authors demonstrate largely underestimate the actual value of income inequality. This is either because households tend to under-report income, especially on returns to financial assets, or because the rich are largely underrepresented in household surveys due to non-response bias as interviewers are often not allowed to pass through the security of gated communities..

While this does not matter for poverty monitoring (which is only concerned with what is happening at the bottom end of the welfare distribution and is traditionally well captured by the existing household surveys), it does matter for inequality if there is evidence that there is a lot of action in the very top end of the distribution. In this case, measures of inequality based on household survey data, which are already high for some countries, would be even higher when incorporating the ‘invisible rich’, and could potentially affect inequality trends as we know them.

Understanding what happening within this group of top income earners may also help to reconcile subjective perceptions of mobility and fairness in society with the reported objective measures of this phenomenon. In some regions such as Europe and Central Asia, there are puzzling divergent trends in observed inequality and economic mobility from household survey data and perceptions of inequality and economic mobility as reported from values and opinion surveys which might be explained by these “missing rich” from the household surveys.

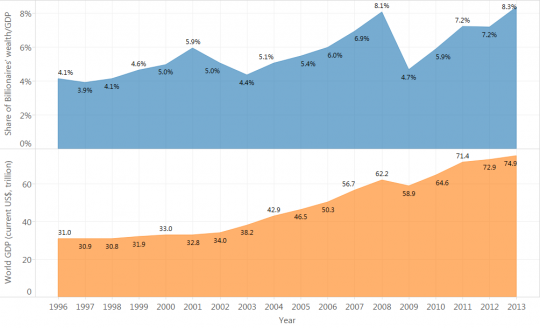

In this short blog post we would like share for your comments, reactions and views a few stylized facts from the Forbes Billionaires database from 1996 to 2014, which might be one of the very few data sources available for us take a peek at the very very very top of the income distribution:

- Inequality between global billionaires is on the rise, as some billionaires are getting richer others are falling behind.

- The total numbers of billionaires (1,645) is also on the rise, with a current total net worth of 6,446 billion USD.

- The rate of growth at the very very very top is on par with the rate of growth of the World Economies in the 2000s. From 2003 to 2013, a period during which the World Economy doubled (based on GDP in current US$ from WDI/World Bank), the share of net worth of billionaires also doubled.

- Results are extremely heterogeneous across regions, with East Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, and Latin America catching up with North America while Africa has continued to lag behind. This is trend is particularly driven by countries such as India, China, Russia, Ukraine and Brazil.

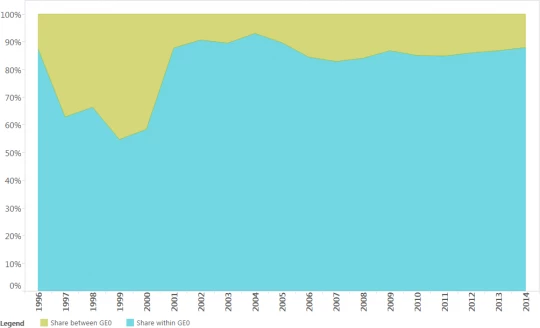

- While inequality between billionaires is increasing overall, inequality between the country of citizenship of billionaires is declining, especially when compared to the mid 1990s. This seems to suggest that the opportunity of becoming a billionaire has been equalized, at least along the dimension of place of birth.

Judging by this evidence presented in the Forbes Billionaires database, it seems that the levels and trends regarding the decline of the global inequality reported by a few authors might in fact look very different if data sources could capture the action at the very top.

And make no mistake, we are interested in looking at the dynamics of top income earners not out of concern for their welfare…this group is most certainly doing quite well. However, the perception and understanding of society towards this group can, and often does, affect social cohesion and helps shape countries’ social contract.

Of course, the empirical anecdotes of this blog suffer from several limitations, to name a few:

(1) We are comparing three very different concepts welfare: Individual net worth as reported from Forbes, GDP as reported from National Accounts data, and total per capita income as reported in household surveys. While GDP is a measure of a country’s income/production rather than wealth, it is probably measured more reliably than wealth and is correlated with a country’s aggregate wealth and income from the household surveys.

(2) The relationship of these variables with income suffers from a number of methodological shortcomings, given that income in the system of national accounts is measured in a different way than the reported income from household surveys. For example, these two systems treat reported earnings from the informal sector very differently.

(3) The geographic dimension used in this study is based on country of citizenship, as this is the way the data is reported by Forbes. Consequently, this may or may not be the country of residence or the country where taxes are paid. Hence, take the country data with a tablespoon of salt.

The intention of this exercise is not to directly inform policy, but rather to support the ongoing debate on the importance of top-income earners data for monitoring and understanding income dynamics and economic mobility in countries around the world. Many developed economies are already systematically sharing anonymized information, often grouped by twentiles from their respective tax revenues systems. However, going forward, it is critical that more countries, in particular developing middle-income economies, also start to do so.

What do you think?

Join the Conversation