Were today’s patterns of wealth and poverty already determined by 1492?

What if today’s patterns of poverty and prosperity were already determined long ago – even before the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the New World in 1492?

That’s the startling question addressed in new research that I’ll soon publish with my colleague Felipe Valencia Caicedo in a forthcoming article, “The Persistence of (Subnational) Fortune,” in the Economic Journal.

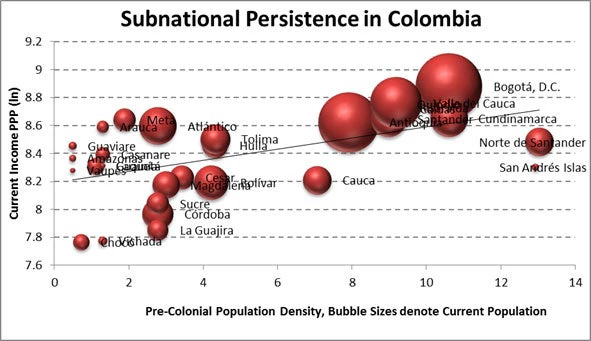

The location of prosperous cities and regions today, within each country in the Western Hemisphere, is closely correlated to the location of indigenous population centers before Columbus’ arrival. Throughout the hemisphere, there is a strong correlation between 15th-century population densities and today’s levels of population density and income.

For modern-day policymakers, the reality of such long-term continuity suggests that any grand-scale efforts to alter long-existing spatial and urban patterns would confront severe difficulties – and thus public-policy changes should be asserted cautiously. The economic advantages of a particular city or region reflect factors that have been accumulated over centuries – and perhaps even millennia.

Focusing on the Americas, we consider the hemisphere’s history as a natural socioeconomic experiment and draw on anthropological and archaeological estimates of pre-colonial indigenous population densities. Following Thomas Malthus, the authors argue that historically more prosperous areas were able to support more population and hence the high correlation with both population and income today is suggestive that “fortune persists.”

Massachusetts and California, for example, had the highest density of native Americans – roughly the same average level of Chile and Argentina – in the territory that would become the United States, and they are among the richest regions today. That is largely also true among Spain’s and Portugal’s colonies in the hemisphere: in Colombia, there is a strong correlation of pre-colonial population density and both population and income per capita (see the accompanying chart). Mexico City, the richest city in Latin America, was founded atop the ancient capital of the Aztecs, Tenochtitlan, the most densely populated pre-colonial area in the hemisphere.

Geographical factors appear to be important in explaining initial indigenous settlements, according to the authors. California, for example, had and retains rich farmland, a productive coast and a temperate climate. But “locational fundamentals” are not enough to explain the patterns we see. Tenochtitlan was founded on a small, swampy island whose chief attraction appears to be that it was un-coveted by the neighboring tribes. The weather was unreliable, the growing season was short and famine was not uncommon. Moreover, frequent flooding inundated the city with its own filth, breeding epidemics.

Why would Cortes would build his capital, Mexico City, in that location? His own writings give us the clues:

In short, he valued not only the available labor force, but also the area’s pool of skilled artisans, dense commercial networks, organizational structures, and collective knowledge – attributes that we associate with dynamic cities and population agglomerations.

Similar phenomena are present in North America, where British, French and Dutch explorers used indigenous knowledge, maps and trade routes to survive, to establish colonies and to establish trading posts and fur-trading networks. The finding of persistence thus suggests the importance of agglomeration externalities and complementarities in production (as conceived by Alfred Marshall in 1890) as well as to increasing returns to scale (as suggested by Paul Krugman in the 1990s).

The finding of persistence is somewhat surprising, as other articles have stressed a “Reversal of Fortune” at the national level – a finding that we replicate. This reversal is attributed to the emergence of growth-inhibiting exclusionary institutions arising from the need to control larger indigenous populations. Although we find some evidence for this – we confirm that slavery, for instance has a depressive effect on current social outcomes – the forces leading to persistence appear to dominate at the subnational level.

Argentina offers an interesting exception to this pattern. Its reversal was mostly due to the removal of royal prohibitions on trade with Spain through the Atlantic port of Buenos Aires: That policy change meant that goods no longer had to be hauled over the Andes to Lima, Peru on the Pacific Ocean and then back overland to the Atlantic Ocean. Releasing this once-suppressed geographic comparative advantage was a powerful shock to geographic fundamentals.

However, this seems to be the exception to the rule, and policymakers attempting to radically change the spatial distribution of economic activity should be mindful of the centuries-old forces working against them.

Join the Conversation