On September 19, 2014, a Kenyan middle-aged woman was waiting for a bus at a stop in Nairobi. When the bus stopped, a group of men surrounded her, and started to strip and assault her for wearing a miniskirt in public. She screamed and cried out for help, but only a couple of brave people reached out and gave her clothes to cover herself.

This kind of sexual violence against women is not unprecedented in Kenya, but this time was different. The brutality of the violence was caught on camera and went viral online. On November 2014 alone, at least four such attacks were recorded across Kenya. The numbers for violence against women are disturbing: according to the Gallup World Poll conducted in 2010 in Kenya, 48.2 percent of women feared that a household member could be sexually harassed.

Yet, few things can be more powerful than watching the violence for oneself. Seeing the videos prompted indignation and courageous actions. This is where the Internet and social media have proven an important tool for sharing information, organizing events, and mobilizing others, all of which can be done at an almost zero economic cost. These videos went viral under the hashtag #mydressmychoice and sparked the “My Dress, My Choice” movement in Kenya. The Facebook page of “My Dress My Choice Challenge” has about 12,000 likes; the twitter account has more than 2,300 followers.

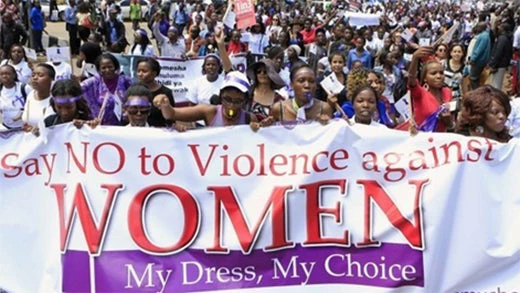

The online campaign and a demonstration on November 17, 2014, which gathered nearly a thousand people in the center of Nairobi, prompted Kenyan leaders to respond. William Thwere Okelo, chief of state of the Inspector-General’s Office, denounced the mob in the videos as “criminal[s]” and promised the public that “the police will take action.” Similarly, Kenyan deputy president William Ruto denounced the attack as “barbaric” and ordered a criminal investigation. As a result, the accused were arrested on November 27 and, if convicted, they will face minimum sentence of ten years to maximum of life time imprisonment.

This is an important milestone, as the existing law (The Sexual Offense Act of 2006) is rarely applied in Kenya. Yet, the real challenge lies in changing social attitudes and behaviors towards women. The local news reported various interviews with local men who think that the mobs “did the right thing,” arguing that there is “moral decay in society” and that the victim learned a lesson. Others were critical of the “My Dress, My Choice” movement out of a belief that a woman wearing a miniskirt lacks “decency.”

Despite the remaining challenges, the fact that “My Dress, My Choice” gained as much momentum as to generate large demonstrations, affect legislation and raise general awareness on issues of gender discrimination and violence signals a strong push in society for gender equality. According to local news outlets, many men marched in solidarity, some in skirts to show their support for the cause. A male artist and activist Boniface Mwangi, who wore a short dress for the march, summarizes the underlying sentiment of the movement: “I think the reason this sparked such outrage is it was so graphic and everyone who watched it felt violated. It could have been my wife, my daughter, my mother.”Similarly, the Facebook group called “Kilimani Mums”or “Kilimani moms” (Kilimani is a residential area west of Nairobi), which played a key role in “My Dress, My Choice”, has grown and expanded the issues it covers. As of February 2015, this group now has more than 42,000 followers and has grown into a network for sharing information about a wide range of subjects, from asking about the best gynecologist in town to sharing their ideas about social issues.

As was the case in Kenya with “My Dress, My Choice”, the internet and social media are increasingly playing a key role around the world in spurring and expanding collective action, especially around “explosive” issues. More recently, for example, similar protests took place in Turkey where men also demonstrated in skirts to protest violence against women (triggered by a brutal murder). Phenomena like “My Dress, My Choice” also show, however, that social media can be part of more profound and long-term changes including issues that are as persistent and deeply-rooted as social norms regarding gender. The 2016 World Development Report on “Internet for Development” will examine in more detail how to harness the potential of the internet to generate collective action, sustain those efforts and promote bottom-up accountability.

Join the Conversation