El Niño weather patterns are known to disrupt commodity production, and by most accounts the current episode will be the strongest on record. Although this El Nino could cause considerable damage at the local level, it is not expected to cause major disruptions to global commodity markets.

El Niño, which raises ocean temperatures in the Pacific, leading to drought and above average precipitation, is forecast to peak in December through February. The weather pattern’s impact is usually strongest in the Southern Hemisphere, particularly in countries in Latin America and East Asia, and in Australia.

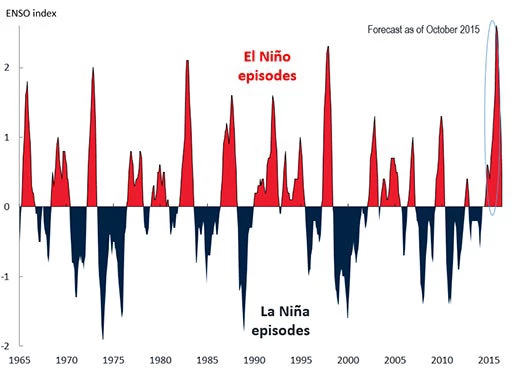

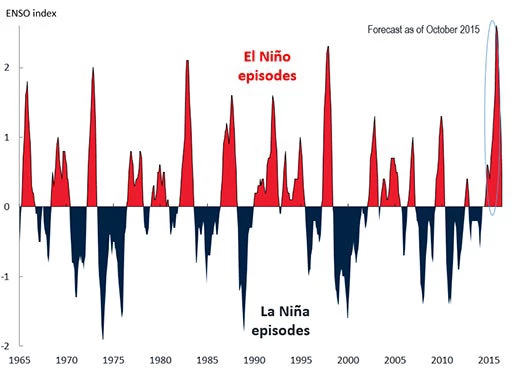

History of El Nino episodes

Despite its anticipated impact on isolated local markets, El Niño is unlikely to cause global agricultural commodity prices to jump. This is because of the ample supply of major commodities, the weak links between global and domestic prices, and past experience that shows little connection between strong El Niños and global price jumps.

That is not say that the weather pattern will have no effect. El Niño can dramatically impacts crop yields – raising them in some places, diminishing them elsewhere. During the 1997-98 El Niño, the strongest occurrence on record, losses were estimated at US$35-45 billion.

The effects of the current El Niño are being felt already. To date, Australia, the world’s fifth largest wheat exporter, has experienced below average rainfall. In East Asia, where conditions are already dry, Indonesia is projected to see a decline of as much as 3 percent of its rice output. In contrast, wetter-than-average conditions in Central Asia could boost cotton exports in Uzbekistan, a big producer of the commodity.

In Central and South America, coffee, soybeans, and some grains could be affected by dry conditions in Central America and wetter-than-normal conditions in Brazil and parts of Argentina.

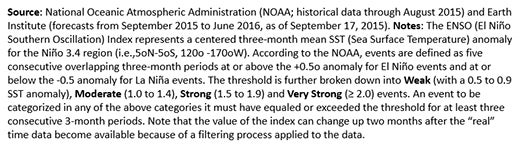

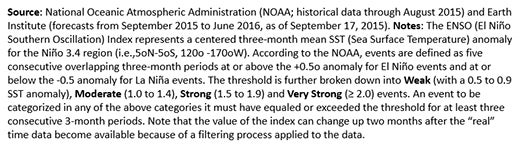

However, most commodity markets, including grains and oil seeds, have abundant supplies. Stocks relative to demand are above the 10-year average for maize, wheat and rice.

Stocks-to-use ratios

Also, there is a weak correlation between domestic and global agricultural prices. Domestic prices are affected by local factors including the weather, foreign exchange fluctuations, transportation issues and trade policies.

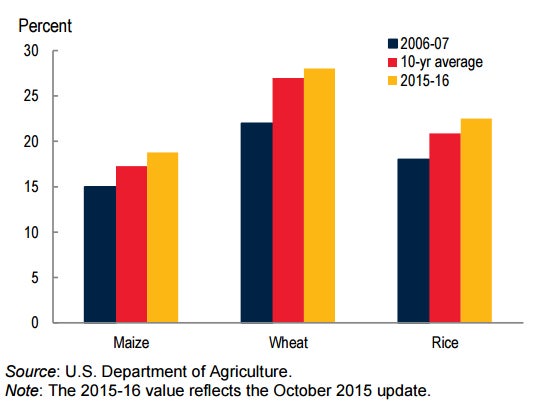

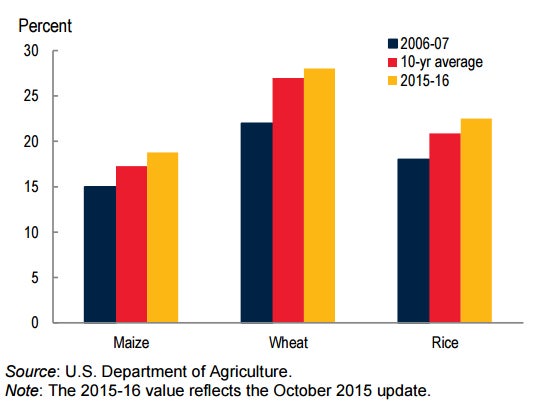

Even when El Niño has been strong in the past, it has not provoked surges in global agricultural commodity prices. During the extreme El Niño of 1997-98, prices actually fell.

El Niño’s and agricultural commodity prices

For more information about El Nino and other commodity market, see Commodity Markets Outlook

El Niño, which raises ocean temperatures in the Pacific, leading to drought and above average precipitation, is forecast to peak in December through February. The weather pattern’s impact is usually strongest in the Southern Hemisphere, particularly in countries in Latin America and East Asia, and in Australia.

History of El Nino episodes

Despite its anticipated impact on isolated local markets, El Niño is unlikely to cause global agricultural commodity prices to jump. This is because of the ample supply of major commodities, the weak links between global and domestic prices, and past experience that shows little connection between strong El Niños and global price jumps.

That is not say that the weather pattern will have no effect. El Niño can dramatically impacts crop yields – raising them in some places, diminishing them elsewhere. During the 1997-98 El Niño, the strongest occurrence on record, losses were estimated at US$35-45 billion.

The effects of the current El Niño are being felt already. To date, Australia, the world’s fifth largest wheat exporter, has experienced below average rainfall. In East Asia, where conditions are already dry, Indonesia is projected to see a decline of as much as 3 percent of its rice output. In contrast, wetter-than-average conditions in Central Asia could boost cotton exports in Uzbekistan, a big producer of the commodity.

In Central and South America, coffee, soybeans, and some grains could be affected by dry conditions in Central America and wetter-than-normal conditions in Brazil and parts of Argentina.

However, most commodity markets, including grains and oil seeds, have abundant supplies. Stocks relative to demand are above the 10-year average for maize, wheat and rice.

Stocks-to-use ratios

Also, there is a weak correlation between domestic and global agricultural prices. Domestic prices are affected by local factors including the weather, foreign exchange fluctuations, transportation issues and trade policies.

Even when El Niño has been strong in the past, it has not provoked surges in global agricultural commodity prices. During the extreme El Niño of 1997-98, prices actually fell.

El Niño’s and agricultural commodity prices

For more information about El Nino and other commodity market, see Commodity Markets Outlook

Join the Conversation