Low-income countries facing a hangover as the commodity cycle turns

Until recently, confidence and expectations for low income countries (LICs) were soaring – with good reason. After all, for most of the 2000s, many LICs managed to consistently post growth rates that were much higher than in the previous three decades (Figure 1).

For metal and mineral exporting LICs – these account for almost two-thirds of LICs[1] – robust global demand for copper, iron ore, oil and high commodity prices filled government coffers and lifted investment and exports. This resulted in a broad based improvement in growth (Figure 2). The 2000s also marked a decade of discoveries, with major oil and gas discoveries in East and West Africa that transformed long term prospects for some LICs.

Today, the outlook is less sanguine and risks are on the downside. As discussed in the June 2015 edition of the Global Economic Prospects, a slow global economy and expanding supply have sent commodity prices tumbling over the past few years. This has cast a shadow over the outlook for commodity exporting LICs.

Great while it lasted

High commodity prices over the past decade generated large positive terms of trade impacts, raising exports and growth. In addition, higher prices also stimulated a surge in global mining and oil and gas investments and exploration, notably in frontier regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa. This resulted in a significant acceleration in investment spending which was sizable in some countries, in cumulative terms amounting to anywhere between 20 - 80 percent of 2010 GDP levels between 2000-11 (Figure 4). Rising revenues from the commodity sector meanwhile enabled an expansion of growth-enhancing government investment, with spillovers to jobs, incomes and consumption.

For several LICs, a spate of “giant”[2] oil and gas finds significantly improved long term growth prospects, notably in offshore East and West Africa, and in the Bay of Bengal (Kenya, Madagascar, Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda, Myanmar).On the negative side, the commodity boom tended to cause an appreciation of the real exchange rate, and hence a loss of competitiveness for non-resource based activity.

Commodities an Achilles heel

With commodity tailwinds turning into headwinds, many commodity exporting LICs have experienced sustained currency depreciation and fiscal tightening pressures over the past year. The associated deterioration in the terms of trade has been large, amounting to nearly 40 percent in Chad and between 10-20 percent in the Dem. Rep. of Congo, Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. This sets back growth, as export and commodity-related fiscal revenues fall.

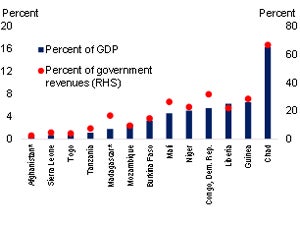

The fall in commodity prices has also complicated the task of macroeconomic management as pressures on public sector balance sheets, currencies and growth have mounted. Reserve buffers are low in many LICs, while large domestic (Figure 5) and external imbalances have emerged in recent years, with significant twin deficits in some countries (Guinea, Kenya, Mozambique, and Niger). Fiscal pressure has mounted in countries where a substantial share of government revenues are derived from the extractive sector. Uganda has rapidly increased debt in recent years to finance commodity-related infrastructure investments, but is experiencing large cost-overruns even as production start dates for a major oil project have been delayed.

Figure 5: LIC fiscal revenues derived from extractive sector

Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) reports.

In addition, with interest rate increases in the United States on the horizon, rising financing costs and low commodity prices may sharply curtail exploration and development activity. In such an environment, country specific factors will likely become more important, including changes in domestic mineral policy regimes that add to production costs.

Sharp commodity price declines are already disrupting exploration and investment in extractive industries. The number of oil rigs—for on-land oil drilling—has fallen by 30 percent from its peak in November of last year in Africa. In Sierra Leone, falling iron ore prices have lowered profits and reduced the market value of the iron ore companies operating in the country (the collapsed London Mining and African Minerals company). This has led not only to lower foreign investments in the sector but also to the shutdown of operations in Tonkolili, the second largest iron ore mine in Africa and one of the largest magnetite deposits in the world.

Moreover, the geological profile and nature of recent discoveries means that some deposits are more expensive to extract than others, notably the ultra-deepwater and pre-salt projects in West Africa and the LNG projects in East Africa. For instance, the cost of building gas liquefaction projects and an associated industrial park in the Ruvuma basin in Mozambique – projects that are in the hands of US group Anadarko Petroleum and Italy’s ENI – are estimated at $26 billion, with Mozambican government estimates even higher at $30 billion. These projects are expected to continue progressing, but more slowly than initially anticipated when prices were high.

Finally, Dutch Disease associated with the commodity boom means that, for many commodity-exporting LICs, shifting growth away from a shrinking natural resource sector may prove hard.

Above ground conditions matter

Thus far, good harvests, remittances, and public investment have cushioned the impact of sharply weaker terms of trade. Many LICs also continue to have favorable below-ground conditions - the value of known sub-soil assets, for instance, is estimated to be barely a quarter of that in advanced economies, and the cost of exploration is also lower, in part because African discoveries are occurring very close to the surface (Figure 6). All this bodes well for long term growth.

Figure 6: Average depth of cover for discoveries

However, over the medium term, the global economic environment will be less favorable to growth in commodity-exporting LICs than it has been over the past decade and a half.

This puts a premium on above-ground conditions. Policy makers should refrain from trying to offset headwinds with demand stimulus that would also deplete already limited buffers. Instead, in the interests of more stable growth in the future, they should focus on structural reforms that support growth in the non-commodity sectors, and may help with continued investment in the resource sector too.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] The definition of current metal and mineral commodity exporting low-income countries is based on that in World Bank (2015), which defines these as countries where commodities comprise more than a quarter of total exports. These include for mining exporters Benin, Burkina Faso, Eritrea, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Sierra Leone, Somalia and Zimbabwe; and for oil and gas exporters Chad, Myanmar, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Countries that have recently started or are expected to start producing over the medium term due to recent discoveries include Kenya, Madagascar, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Uganda.

Join the Conversation