Women of the Délali Association | © World Bank

Women of the Délali Association | © World Bank

Sustainable development has three foundational pillars —environmental, economic, and social. Balance among all three is necessary to achieve our collective Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). But social sustainability, by nature, is the most elusive and complex. When rain forests are destroyed, we understand what is lost; when hyperinflation wipes out wealth, the costs of economic mismanagement are clear. But what does sustainability look like when people are at stake, when inequality leads to social unrest, or infrastructure projects destroy indigenous communities? In short, what is social sustainability, why does it matter, and how can it be bolstered?

These questions are critical because social sustainability, like environmental and economic sustainability, is increasingly under pressure. The world faces unprecedented and growing challenges around climate, conflict, and the impacts of COVID-19. Their socio-economic fallout—including the structural inequalities these crises have exposed—are magnifying tensions and accelerating a range of worrying trends, from declining trust to increased social unrest.

Achieving social sustainability through collaboration and collective action is urgently needed to address today’s mounting challenges. While economic and environmental sustainability remain vital, these alone are not enough. In our new publication, Social Sustainability in Development, we argue that social sustainability reflects whether people feel they are part of development and believe that they will benefit from it. Socially sustainable communities and societies are better equipped to tackle shared challenges in ways perceived to be fair and just, enabling all members to thrive over time. This breaks down into four components that form a simple conceptual framework for social sustainability (figure 1):

- Social cohesion: shared purpose, trust, and willingness to cooperate within and across communities, and between communities and the state.

- Inclusion: access for all to services, markets, and the opportunity to participate in society and live with dignity.

- Resilience: where everyone, including poor and marginalized groups, are safe and can withstand shocks and protect their cultural integrity.

- Process legitimacy: a relatively new concept focusing on how public decisions get made and implemented, ensuring that stakeholders—especially those who stand to ‘lose out’ —accept these decisions as fair and credible.

Figure 1: Social sustainability

Like its economic and environmental counterparts, social sustainability is both aspirational and subject to constant change. The three components are relevant both for making policy and implementation and can vary over time. The far-left side of the spectrum indicates total absence of the component; the far-right side indicates full presence. Process legitimacy influences how decisions are made and implemented (figure 1). While the four components are complementary, policymakers often choose or must prioritize between them. Such trade-offs unfold within the ‘policy arena’ —the spaces where public decisions get made amid competing priorities, budget constraints, and time pressures.

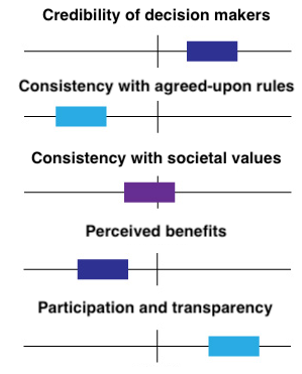

Social sustainability is less a technical achievement than an outcome of a highly social process that constantly evolves. In this sense, process legitimacy is critical, ensuring that any tensions are meaningfully accommodated. Process legitimacy is strengthened when authority figures have credibility and decision-making is participatory, transparent, and aligned with local rules and values while offering clear public benefits. These ‘drivers’ are mutually reinforcing but also function independently (figure 2), and the most “typical” scenarios are mixed (figure 3).

Figure 2: Drivers of process legitimacy (hypothetical example)

Note: For each driver, the location of the bar on the spectrum reflects the current level for this hypothetical community or society, with the far-left side indicating total absence of the driver and the far-right side indicating full presence.

Figure 3: Process legitimacy—illustrative scenarios

Note: For each scenario, the five horizontal lines represent the five drivers of process legitimacy. Each bar’s location on the spectrum reflects the absence or presence for that driver in a given scenario, where the far-left side indicates weakness and the far-right side indicates strength.

While social sustainability has intrinsic value grounded in human rights and aligned with the SDGs, it also matters for development outcomes. The World Bank’s new Social Sustainability Global Database (SSGD), for example, builds evidence on how the four components of social sustainability correlate with poverty reduction, human capital, and inequality (figure 4) using 71 indicators for 236 countries. Several of these correlations are quite strong —namely, inclusion and process legitimacy with poverty reduction and human capital, as well as process legitimacy with inequality. However, a key finding of our book is that more efforts are needed to measure, analyze, and understand the role and impact of social sustainability and its components.

Figure 4: Correlations between the four components of social sustainability

So, what does social sustainability look like in practice? Development projects increasingly focus on inclusion. For example, disability inclusion provisions in education in Rwanda, health services targeted to the Roma, or improved services for migrants and host communities in the Horn of Africa. But the challenge is making these efforts more systematic, strategic, and explicit. Although the World Bank is taking steps in this direction, including through enhanced country partnership frameworks that identify vulnerable groups and structural barriers and propose targeted interventions, more can be done.

The Bank is also investing in resilience at all levels. Examples include health, water, financial, or food systems and, at the household level, automatic safety nets after shocks. But more efforts are needed at the local level because communities are often the first line of defense when shocks occur. In Kenya, the Financing Locally Led Climate Action (FLoCCA) Program supports partnerships between citizens and local governments to assess climate risks and identify socially-inclusive, locally-tailored solutions.

Efforts to promote social cohesion seek to build trust and create an environment where communities can tackle challenges together. In the Philippines, a Bank engagement in Mindanao brought together ethnic groups engaged in conflict to collectively allocate resources and solve problems. In the Sahel, similar projects are resolving farmer-herder conflicts while also strengthening their relationships with local government, which is key for addressing broader challenges like climate and fragility.

Strengthening process legitimacy requires opening the policy arena so all groups can be heard – a critical step for building consensus on climate and related challenges, like inclusive transitions. In South Africa, for instance, the closing of the Komati coal-fired power plant is being accompanied by efforts to include communities who live around the plant in the planning process for a greener future.

These efforts and countless others are starting to close a critical gap in today’s development agenda, but a whole of society approach is needed. Social sustainability is also key in building the coalitions and trust necessary to address climate change, preserve biodiversity, and reduce conflict. For that reason, it must sit alongside environmental and economic sustainability to ensure success over the long term.

Join the Conversation