Trade unexpectedly rebounded in 2017, after a period of slow growth and despite recent uncertainty about trade policy. Growth in the volume of trade in goods and services jumped to 4.3 percent in 2017—the fastest rate in 6 years (Figure 1). The recovery was widespread, with the largest contributions to growth coming from East Asia and the Euro area. Data just released for the first quarter of 2018 suggests that the faster growth persists: merchandise trade volumes grew by 4.4 percent in the first quarter of 2018 relative to the first quarter of 2017. What explains these developments?

The World Bank’s Global Trade Watch (2018) provides some preliminary answers. Cyclical factors drove better trade performance in 2017. Trade grew faster, first, because real gross domestic product grew faster. Real GDP growth, at 3.7 percent at purchasing power parity weights and 3.0 percent at market exchange rates, was the highest rates since 2012 (Figure 1).

Increased investment growth also played a role in the revival of trade (Figure 2). The rebound in global investment growth accounted for three quarters of the acceleration in global GDP growth from 2016 to 2017. Investment is the most import-intensive component of aggregate demand, and capital goods production has longer global value chains (GVCs). Preliminary monthly data indicate that in 2017 import values of capital goods such as machinery and electrical equipment grew at the fastest rates since 2012 and that they have been the most significant contributors to 2017 nonfuel import growth in the European Union and United States. In both cases, an increase in imports of machinery and electrical equipment from East Asia, especially China, drove the 2017 growth.

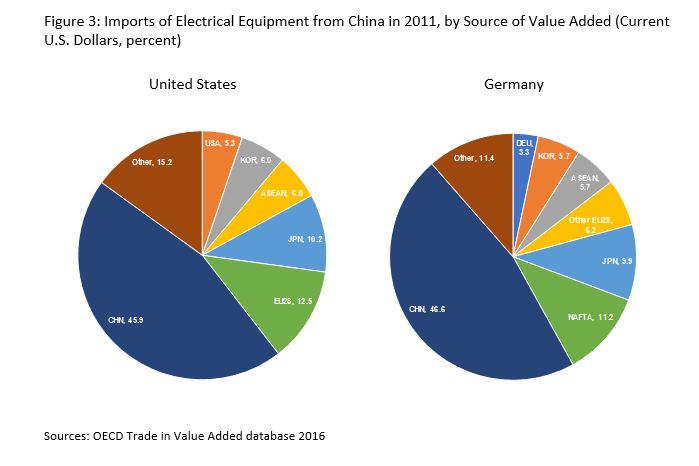

The impact on trade of increased demand for capital goods was magnified by global value chains. Even though there was a surge in gross imports of machinery and electrical equipment from China, a substantial part of the value added originated in other countries. In the latest year for which data is available, less than half of the value added in imports of electrical equipment imported from China by the United States and Germany was Chinese and the rest from several other countries (Figure 3).

Despite these signs of trade vitality, old and new factors constrain world trade growth. While trade volume grew faster than real GDP in 2017, the gap between the growth rates of the two indicators is still about the same as the average gap during 1980-1990 and well below the one prevailing in the 1990s, when trade grew twice as fast as real GDP (Figure 1).

The maturation of global value chains is a structural factor slowing down trade growth. Trade growth raced ahead of output growth in the 1990s as production fragmented internationally into GVCs, leading to a rapid surge in trade in parts and components. This process appears to have matured in recent years (Figure 4), leading to a deceleration in trade growth.

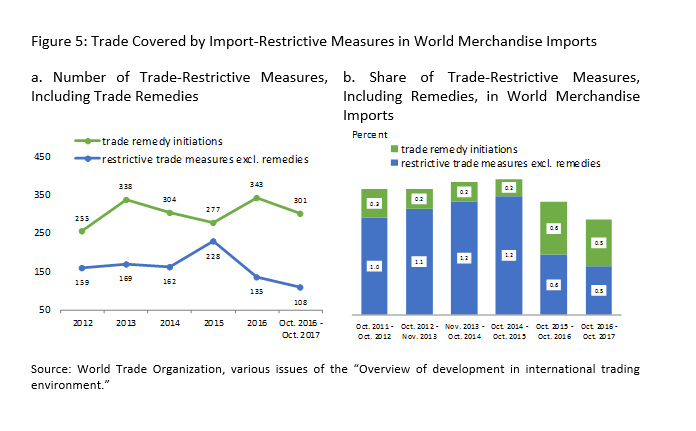

A second factor is the prospect of protection and policy uncertainty more generally. The share of merchandise trade that trade-restrictive measures cover remained stable at approximately 1 percent in 2017 (Figure 5). But the portion due to trade remedy initiations—a harbinger of future protection—has increased significantly since 2015. And restrictive measures imposed in the first quarter of 2018 may have a delayed effect on trade growth since trade contracts tend to be signed weeks or months in advance.

The future growth of trade will depend on how effectively existing trade agreements prevent recourse to protection and how rapidly new agreements boost trade. While there is a serious risk of policy reversals in some cases (e.g., North American Free Trade Agreement, Brexit), in many other cases, often involving developing countries, new trade agreements have been concluded or are being negotiated, including the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for a Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, and the Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA) in Africa. If these negotiations are successfully concluded, the effect on trade could be substantial and long lasting.

Join the Conversation