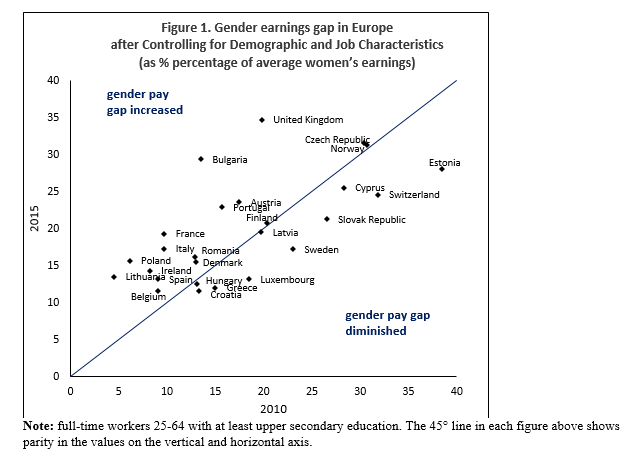

Across European countries, women continue to earn less than men. Looking at data for full-time working women across 30 countries, we find that women would have needed an average raise of 19 percent of their hourly wage to match male wages. Take France, for example, where the gap is close to the regional average: this would mean going from 584 Euros to 697 Euros for a 40-hour work week. In fact, in some countries the gap was higher, reaching 1/3rd of women's salaries in 2015 (see Figure 1). However, the lowest observed gaps are not found in Scandinavia, as you might expect, but in Croatia, Greece, and Belgium, where women would require a 12% wage increase to fill the gap. And these gaps have persisted over time. Over a five-year period, the gap decreased in only 10 of the 30 European countries we looked at. The most notable decreases were in Estonia (10 percentage points), the Slovak Republic (5 percentage points), and Switzerland (7 percentage points). For others, the gap has increased, particularly in Poland, Bulgaria, Lithuania, and France, where the gap has doubled, while in some Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway) and Latvia, the gap has remained relatively constant.

Source: World Bank calculations using EU-SILC surveys for 30 countries in Europe.

What explains these gaps? We focus on the ‘usual suspects’ such as differences in education, family formation, and job characteristics, and use a methodology where we match men and women on those characteristics. We find that for both Eastern and Western European countries in our sample, the gender earnings gaps not only remain after comparing men and women with the same demographic characteristics (age, marital status, level of education, presence of a child under 6, and urban/rural location), but that these gaps are even higher than the simple gaps shown in figure 1, in line with previous work.

This means that even when women have characteristics that should make them better paid, such as more years of education, they still earn less than men. In other words, there is a sizeable “unexplained” portion of the earnings gap that persists even after taking into account the usual factors. This partly contradicts what we see when we look, for example, at education gains. The gender gap in education enrolment has disappeared in most of Europe, and in fact boys and young men are now lagging behind girls and young women, but we still find that women with the same education level as men (and of the same age) are not earning as much as they should.

Marriage and children explain some of the wage gap we observe -but only about a third of it and even after taking into account job characteristics such as the sectors and occupations where women and men work, we are still left with a persistent and sizeable portion of the wage gap that cannot be explained. More importantly, we are also left comparing a very small group of men and women, suggesting that, as other data and research have pointed to, there is gender segregation in economic sectors (and in occupations). Sex-segregation is an important element when it comes to account for earnings differences among men and women. Hence, we see that female-dominated sectors, such as education and health, experience the lowest unexplained gaps.

Despite this, the progress that some countries have made is a source of hope, but active policies to close wage gaps are required. The European Commission recommendations point to several possible directions, from pay transparency where workers can compare their wages with others, to improving legal frameworks, like the recently approved law in Iceland aimed at closing the gender pay gap. However, there is still much more to be done to continue to improve hiring and wage policies across the European region.

Join the Conversation