Women of Takalafiya-Lapai village (Niger State) are beneficiaries of Nigeria's Fadama II project.

Women of Takalafiya-Lapai village (Niger State) are beneficiaries of Nigeria's Fadama II project.

Nigeria, like other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, is facing a demographic boom. By 2050, its working-age population will have increased 125 percent. At current GDP growth rates, the local labor market will be unable to absorb all the new entrants. One way for Nigeria to reduce this pressure, and make the most of remittance and skills transfers, is to promote new legal labor migration pathways with countries of destination across the globe. The World Bank has just started a new task aimed at promoting such pathways; the content and potential impact of which this blog will discuss.

The Nigerian labor market: now, and in the future

In 2018, Nigeria surpassed India as the country with the largest number of people living under US$1.90/day. Despite a decade of strong economic growth before the recent recession, poverty and vulnerability levels remain notably high, largely due to a lack of productive, gainful employment opportunities for its increasingly large working-age population. Data from the Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics shows that Nigeria’s unemployment rate has skyrocketed to 23.1 percent (from 7.5 percent in 2015). Unemployment has been rated as the most important issue facing the country, above management of the economy, poverty, corruption, and electricity.

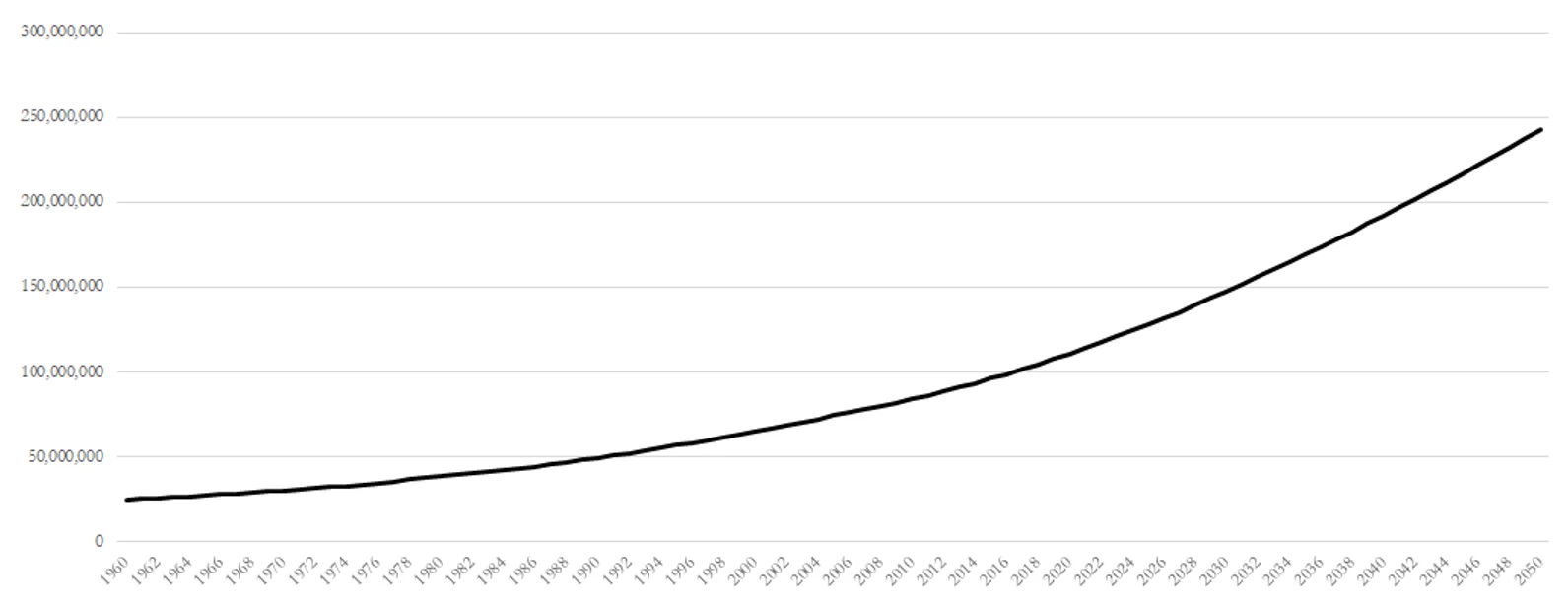

This situation is set to get worse. By 2050, Nigeria’s working-age population will have increased 125 percent (see figure 1). It is estimated 30 million additional jobs will be needed by 2030 to keep the employment to population ratios at current levels, let alone improving them. Even maintaining the assumption of an economic growth rate of 6 percent per year, only one in four Nigerians entering the labor market will be able to obtain good, wage-paying jobs in the formal sector.

Figure 1: Nigeria’s working-age population (15-64) is set to increase 125 percent by 2050

Source: Those aged 15 to 64 will increase from 107,702,000 in 2019 to 242,994,000 in 2050 according to World Bank data. The data uses a base year population estimate by age and sex, and assumptions of mortality, fertility, and migration, using the UN’s Population Division’s medium variant.

The lack of skilled, meaningful work at home, both now and in the future, is creating large migratory pressures. In 2018, an Afrobarometer poll found that one in three Nigerians want to move outside the country. And given an absence of legal pathways for migration, many have moved illegally. In 2016, Nigerians were the largest population group entering Italy and Greece, and they are the largest cohort trapped in Libya. Thousands are being returned, but without substantial job creation in Nigeria, and / or new legal pathways, Nigerian youth will continue to undertake dangerous journeys to search for better employment opportunities.

The role of migration in addressing this problem

Much can, and should, be done domestically to improve the skills of this new working-age population and link them into good employment opportunities at home. Currently, the formal skills development system in Nigeria suffers from capacity constraints and low external efficiency, due to the absence of linkages between curriculum design and labor market information (LMI), especially from industry and enterprises. Only about 2 percent of all secondary education students are accommodated in technical colleges. This results from years of under-investment in the Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) eco-system. Ongoing World Bank engagements through the Edo Economic Transformation Project and the Innovation Development and Effectiveness in the Acquisition of Skills (IDEAS) Project are helping create better linkages between industry and curriculum design domestically in Nigeria.

But more could be done to add an international labor migration lens to these efforts — looking at external destinations as a potential source of employment for Nigerian jobseekers. Nigeria’s National Policy on Labor Migration 2014 recognizes this, committing to “undertake projection of human resource requirements in countries of labor and skills demand, with special attention to emerging skills requirements, to anticipate meeting demand with matching skills”; “develop financial support schemes to help youth acquire skills that are sought after in both domestic and foreign labor markets”; and “promote the participation of employers and trade union organizations in the provision and funding of vocational training and skills upgrading institutions, to meet international skills requirements.”

And these requirements are acute. Many developed countries are facing significant labor shortages, due to declining working-age populations, and are in need of low- and semi-skilled labor. Nigeria is well placed to plug these gaps. But the terms of how this migration will happen are likely to depend on both how prepared Nigerian young jobseekers are for employment outside the country (skills, language, etc.) as well as how effective the labor migration management system in Nigeria is to support the move. There is a need to maximize the benefits and minimize the costs of international labor migration for Nigerians, something the World Bank has just started to work on.

The Global Skill Partnership model

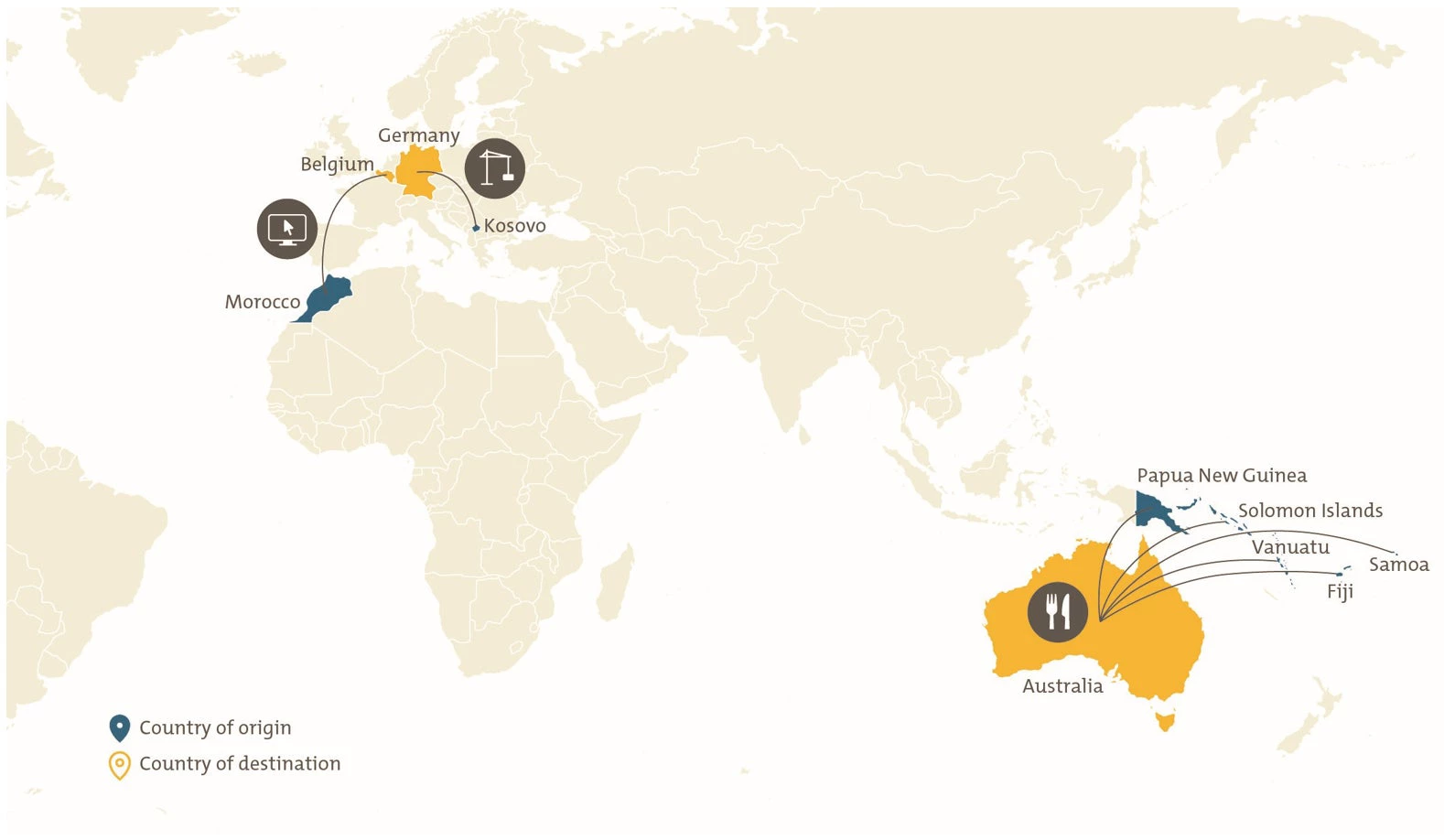

One avenue being explored by the World Bank is a Global Skill Partnership — a bilateral agreement between equal partners. The country of destination agrees to provide technology and finance to train potential migrants with targeted skills in the country of origin, prior to migration, and receives migrants with precisely the skills they need to integrate and contribute best upon arrival. The country of origin agrees to provide that training and gets support for the training of non-migrants too—increasing rather than draining human capital. The Global Skill Partnership model is being trialed around the world (figure 2) and was endorsed, by name, in the Global Compact for Migration, approved by 163 countries, including Nigeria.

Figure 2: Where the Global Skill Partnership model is being piloted

The World Bank is currently exploring where Nigerian job-seekers can be competitive in external labor markets, and which skills are in demand in both contexts. This analysis will allow Nigeria to craft a pathway that maximizes the benefits of migration to all parties, including by promoting development and combatting skills drain at home. As shown above, this model will benefit both countries, and promote sustainable economic development. To date, the number of workers involved in these projects is small, and we acknowledge that the model is unlikely to meet all demand, both in Nigeria and abroad. But it should be viewed as one tool which can be used to manage migration in a mutually beneficial way — a tool that is hitherto missing from the development community’s toolkit.

The scale of the demographic shifts highlighted above means Nigeria, and key countries of destination, cannot wait until migration flows visibly increase to implement new legal labor migration pathways. Tools such as the Global Skill Partnership should be tested now, in a period of relative manageability, before the scale and pace of migration makes innovation difficult. The work conducted by the World Bank, to map and project future skills pressures in Nigeria, is an excellent start. Countries of destination now need to step up — to promote development in Nigeria and help their own economies.

————

To learn more about the project, please contact Samik Adhikari.

Join the Conversation