Judge's gavel and flag of India.

Judge's gavel and flag of India.

Constitutions, and the judiciaries that uphold them, have profound impacts on democracy, economic activity and social stability (Sunstein, 2001; Persson and Tabellini, 2005; Durlauf, 2020). India’s constitution, which promises its citizens "equality before the law" as well as "the equal protection of the laws", has been proactively safeguarded by its courts (Austin, 1997) and contributed to the resilience of India’s democracy (Khosla, 2020; Kapur, 2020).

While India’s judiciary -- the largest in the world -- has achieved a great deal of trust from Indian citizens (Krishnaswamy and Swaminathan, 2019), the actual processes of justice remain poorly understood. The paucity of publicly available empirical data has been a major barrier for empirical scholarship (Bhupatiraju, Chen and Joshi, 2020). Little is actually known about how people interact with the judiciary, the networks of preferential access that operate in the institution, or the mechanisms through which structural inequality in the broader population are addressed (or not).

In a new working paper we study the role of identity in the formal judicial system in the state of Bihar. This is one of India’s poorest states, but has recently experienced an impressive growth turnaround. We use a novel dataset of more than one million cases filed at the Patna high court between 2009 and 2019. We supplement this with data from several sources: (a) Socio-economic Caste Census (SECC) aggregates for Bihar; (b) A database of about 1 million registered farmers from the Bihar Cooperative Department; (c) A database of 300,000 employees of the Bihar state-government who have disclosed their financial status; (d) A database of all judges who have served at the Patna High Court. For descriptive research we also draw on a newly compiled dataset of Indian surnames from Ancestry.com and familysearch.org, two leading websites that have attempted to gather detailed ancestral records for individuals who once served in the British Indian Army or the British Indian government that was present in India until 1947. To all these data, we apply some simple methods of machine learning to infer gender, religion and caste of petitioners, respondents and their advocates.

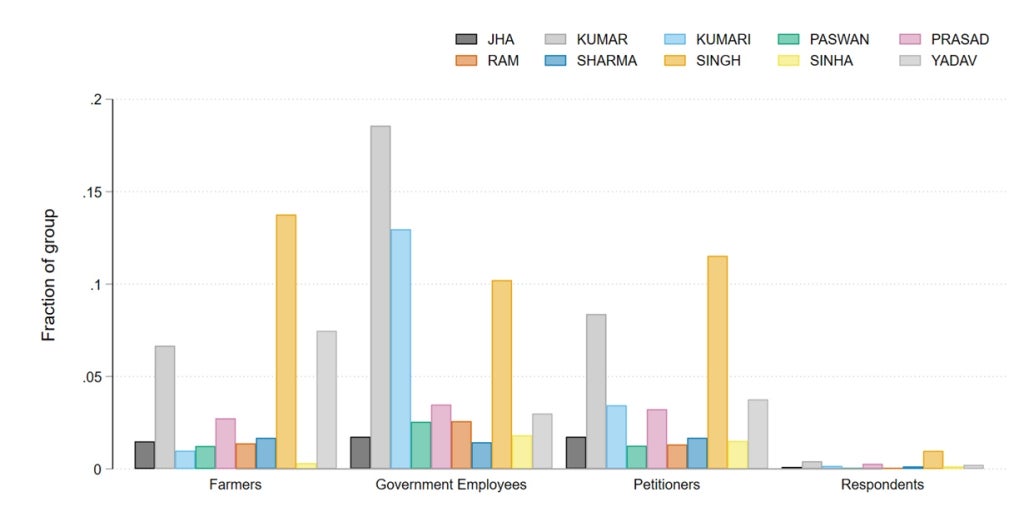

The identification of the dominant last names among petitioners and respondents, together with our inferences about the caste identities of these individuals, led to some interesting findings. We immediately observed that the top 10 last names across all these data sets (except the judges) are Kumar, Singh, Sinha, Mishra, Prasad, Yadav, Ramand and Jha. Probably more interestingly, we find that most of the surnames in the top-10 list of names in the institutions we consider here are caste-neutral which means that they conceal a person’s caste.

Figure 1: Proportion of sample, by top-10 last names

We also found that certain last names are overrepresented in specific occupations: Kumar for example, accounts for 19% of all senior government employees but only 7% of farmers and 2% in the SECC data. Even in this unequal playing field, judges are quite distinctive. Of the 84 judges observed over the 11-year period, only 6% are women and less than 10% are Muslim. In general, women are underrepresented: although they constitute half of the population, their share in the different professions varies significantly.

In the main analysis of the working paper, we use the data to understand how last names and group identities correlate with the process of justice within the court. Specifically, we study how often some agents in the judiciary belonging to an identity group appear in our data together with other agents of the same or a different identity group. Next, we check if this number is above expectations given the number of agents with these identities, the case-types, etc. For instance, we study if a Muslim petitioner is overly likely to have a Muslim judge attributed to his or her case. With this kind of analysis, we answer three different questions.

Figure 2: Networks between judges and lawyers, 2009-2019

Note: Data restricted to the names that appear at least 1000 times; “J: Judge”, “A: Advocate”, “L: Litigant”; size of the node is proportional to the weight of the edges that are associated with it. Lowest weight is 1000; Highest weight is 20,000.

Do petitioners and judges match based on their caste, gender or religion?

There is no official mechanism for a petitioner to choose a judge. Through the roster system, which contains the allocations of cases to specific judges as decided by the chief justice, the court strives to ensure that case-assignment is as objective as possible. Additionally, the court strives to ensure that judges do not work with parties with whom they have had any familial or social connection. In other words, there should be no mechanism by which an influential petitioner, with high social status, can ensure that their case is heard by a specific judge from the same social group. Our results show no identity-based matching between petitioners and judges. This is reassuring in the sense that it suggests that the case-assignment seems, at least in general, to be objective and independent of the agents' identities.

Do petitioner’s advocates and judges match based on their caste, gender or religion?

Petitioners can change advocates during the process to potentially adapt their strategy to the judge attributed to their case. However, following the same argument of objective case assignment as for the petitioners themselves, we would expect to observe no identity-based matching between the initial (filing) advocate and the judge. Here, as for petitioners, we do not find significant matching between petitioners’ filing advocates and judges.

Do petitioners and their advocates match based on their caste, gender or religion?

The rule of law provides petitioners considerable freedom of choice over whom they want as advocate. Petitioners may prefer advocates from a single community. Indeed, we find strong evidence that Muslim petitioners chose more often Muslim advocates and caste-neutral petitioners chose more often caste-neutral advocates. Yet there is no such effect for women or scheduled cast petitioners.

In summary, we do not find evidence against random matching between judges and petitioners and their advocates. However, we observe identity-based matching between petitioners and their advocates. We consistently find evidence for limited representation and power for women and individuals who are from the scheduled cast community. The significance of caste-neutral names is a key finding of this paper. While the practice was adopted to reduce the salience of caste in formal institutions in Bihar, paradoxically, the groups that have adopted this practice may have formed strong networks of their own.

Join the Conversation