Shu Tan, from the Black H'mong tribe, has managed to succeed despite the odds for ethnic minorities in Vietnam.

Shu Tan, from the Black H'mong tribe, has managed to succeed despite the odds for ethnic minorities in Vietnam.

Pretend it’s 1998, and we are at the Sapa Town Center in northwestern Vietnam.

There, if you met and told a 12-year-old named Shu Tan that some 20 years later international media would be eager to feature and discuss her accomplishments, you might receive a blank stare in response. She would not understand Vietnamese – let alone English – since she only spoke her tribe’s dialect, Black H’mong. She would also be much too focused on selling her brocades to chat. Failing to do so meant sleeping on the street with an empty stomach. With just three years of schooling, she dropped out to work and support her ailing father.

But in 2019, her story is quite different. Shu Tan runs Sapa O’Chau: an internationally-acclaimed tour operator providing walking tours, homestay treks and mountain hikes in Sapa. She is fluent in Vietnamese and English, finally has her high-school degree, and not only lifted herself out of poverty but created opportunities for others to do the same.

Shu’s success demonstrates that regardless of ethnicity, every human being has potential and will flourish under the right conditions. Yet her remarkable rise is a rare exception among ethnic minority groups in Vietnam – which make up 14% of the population but accounted for 73% of the poor in 2016. Despite Vietnam’s impressive efforts to reduce overall poverty, ethnic minorities still lag behind compared to the Kinh majority.

While Vietnam’s Human Capital Index is at 0.67 – exceeding the upper-middle-income average – such indexes for ethnic minorities groups are consistently lower. A closer look at Vietnam’s Index data indicates this inequality clearly: nearly 1 in 3 ethnic minority children are affected by stunting, more than twice as much as the Kinh majority – and a rate so alarming it is equal to that of many Sub-Saharan African countries.

An intricate set of causes drive this trend, according to our latest study. One is cultural norms, which call for early marriage and childbearing; 23.9% of ethnic minority women had their first child between the ages of 15 and 19. And given their mother’s young age, many of these babies’ development is affected in the womb. Toddlers’ diet is of lower quality when compared to their Kinh counterparts. Poor hygiene also prevents these children from fully absorbing the nutrients they do receive.

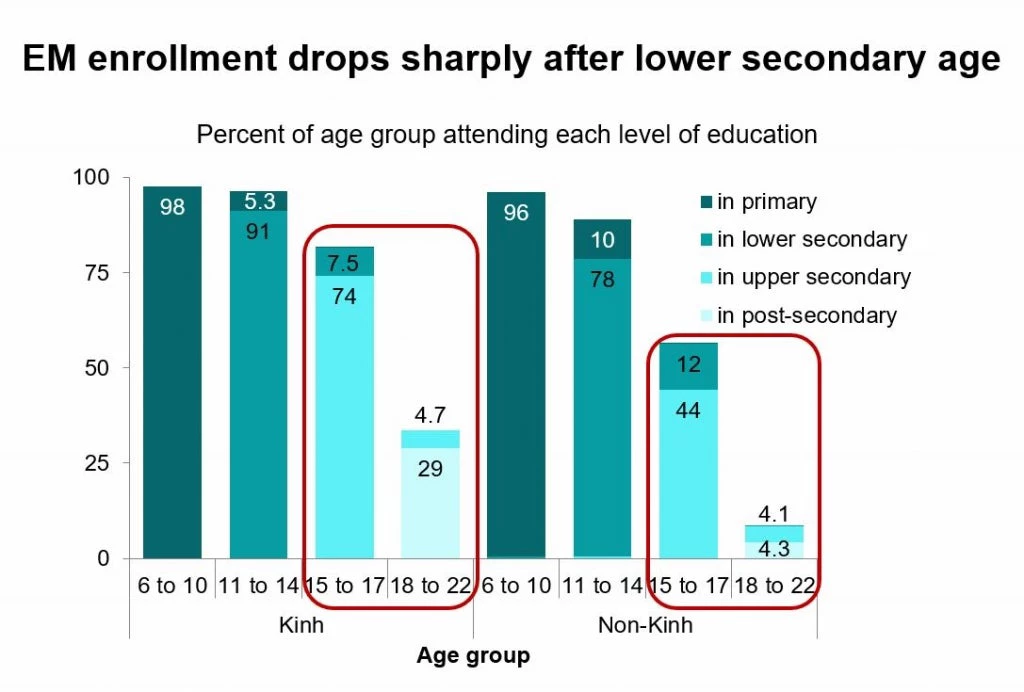

Interestingly, when it comes to school enrollment, Kinh and ethnic minority children share similar rates during primary and lower secondary school. Once they enter upper-secondary level, or high school, their paths diverge once more, with a 30-percentage-point difference. Ethnic minority children also tend to lag behind grade levels, with 12% of 15 to 17-year-old ethnic minorities who should be in upper secondary level are enrolled in lower secondary level, compared with 7.5% of Kinh.

Ethnic minority children who drop out of school are more likely to report being needed for agricultural work than Kinh children. Over-age enrollment, in addition to the lower quality of schooling available, largely explains why ethnic minority children tend to drop out around age 15. For ethnic minority girls, early marriage also contributes to higher dropout rates. This lack of education reduces access to wage jobs with good benefits, resulting in lower earnings and overall resiliency to natural and economic shocks.

A large share of government expenditures is already spent on education (21%) and health (8.9%), but we argue that there is room for efficiency gains. The next round of the National Targeted Programs on poverty reduction should explicitly focus on smart human capital investments, apply a results-based funding mechanism, and include an effective monitoring framework. A focus on human capital outcomes would ensure that the next round of National Targeted Programs includes nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions, specific programming to increase access to and quality of upper secondary and tertiary education and support for ethnic minorities to make a smooth school-to-work transition.

Ethnic minorities’ voices should also be front and center to ensure that programs are sensitive to their cultural beliefs and practices. Involving ethnic minorities in the design of interventions and including mechanisms for incorporating feedback during implementation increases the chances of success. For interventions to reach ethnic minorities, literacy constraints, language preferences, and cultural values should be considered.

To create breakthroughs in service delivery for the lagging regions, innovation and private sector participation will be imperative. For instance, when it comes to nutrition, private sector compliance with existing regulations on mandatory food fortification with micronutrients and the ban on advertising of breast milk-substitutes could be enhanced.

Today in Sapa, you can spot many ethnic minority children living Shu’s journey – going out every day to sell souvenirs to tourists. Twenty years from now, who among them will become the next Shu Tan? Without sustained focus on bringing transformational human capital outcomes to ethnic minority groups, her story will remain an exception, and not the rule.

Join the Conversation