Gender and education in Indonesia

Gender and education in Indonesia

In the 1970s, the Gender Parity Index (GPI) for school enrollment rates (the ratio of girls to boys enrolled) for children 7-12 years old was 0.89, signaling a significant disparity in favor of boys. The gap was even wider in older children. However, by 2019, Indonesia achieved gender parity in education participation at the national level, with a GPI of 1.00 for school enrollment rates of children 7-12 years old.

A recent World Bank study, supported by the Australian government, examined gender issues in education and found that while national averages have improved, significant differences exist at the subnational level, both in favor of boys and girls.

Key findings and takeaways

- School participation: Both boys and girls face disadvantages in different regions. For example, in Sukamara Regency, Central Kalimantan, 61 percent of boys age 16 to 18 are enrolled in school, while the percentage of girls enrolled is 95. However, in other regions girls also face disadvantages. For example, in Probolinggo Regency, East Java, the percentage of boys enrolled is about one and a half times more than the percentage of girls enrolled.

Gender Parity Index based on School Participation Rate 16- to 18-year-olds across districts in East Java Province

Source: Susenas 2018, processed.

|

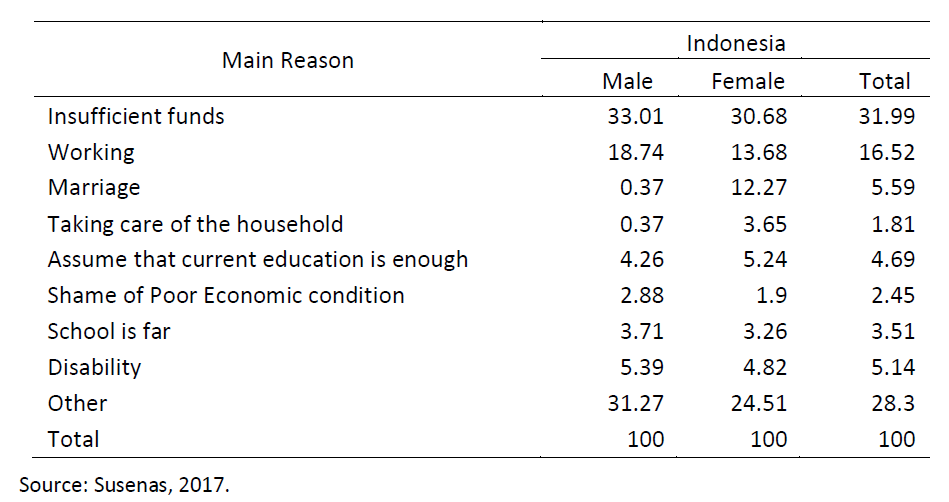

- Socioeconomic and geographical disparities seem to play important roles on whether students complete their schooling. Adolescents of lower secondary school age from the poorest households are higher than four times more likely to be out of school than those from the wealthiest households. Economic-related conditions are observed to be the main reasons for not going to school. The out-of-school population is also concentrated among children living in rural, remote areas.

Main reasons for dropping out from school by sex (percent)

- Child marriage: Girls continue to be disproportionately impacted, with large variations at the subnational level. Early marriage and schooling are inversely correlated, particularly for girls, as many drop out of school if they get married. Though Indonesia’s child marriage rate has been declining in recent years, it is still high. The study found wide variations at the sub-national level. For example, West Sulawesi had the highest prevalence of early marriage in 2015, with 34.2 percent of ever-married women aged 20-24 married before age 18. In contrast, the Riau Islands had a lower but still significant rate of 11.7 percent.

- Bullying impacts boys and girls differently: The study confirmed findings from earlier studies on bullying in schools. While boys have a higher risk of bullying/physical violence, girls, by comparison, were more likely to experience sexual-based violence and emotional/psychological violence.

- Nationally, even though girls are performing better than boys in school, women work less, earn less, and are promoted less. Women are still under-represented in school and governmental leadership positions. Through interviews, we learned that women are promoted less often and seek fewer opportunities for promotion. Women achieve lower scores in bidding processes for promotions and are less able to participate in training for higher echelon positions due to time constraints and responsibilities at home due to a lack of adequate childcare facilities at district, provincial and ministry offices. Women and men both noted that some positions are targeted specifically for men and that men are seen as better leaders.

- Within the education workforce, this translates into men occupying the majority of management positions. Across MoRA and MoEC schools, women represent over half the teaching workforce at the primary, lower secondary, and upper secondary school levels. However, when it comes to managing and leading schools, data show that men dominate these roles. At the primary level, women only represent 31 percent of principals in MoRA and 43 percent in MoEC schools, with figures falling as the school level increases. In upper-secondary MoRA schools, only 19 percent of school principal positions are occupied by women, whereas in MoEC upper secondary schools only 22 percent of all principals are women.

Our study recommends a number of options for Indonesia to address these issues and continue to build on the strong strides it has already made on gender parity in education. These include: analyzing subnational data to identify gender imbalances and developing possible solutions, gender-sensitive teacher training, ideas on how to encourage more women to be school leaders, and providing adequate childcare facilities to civil servants. You can read the full findings from the study and our recommendations here.

Join the Conversation