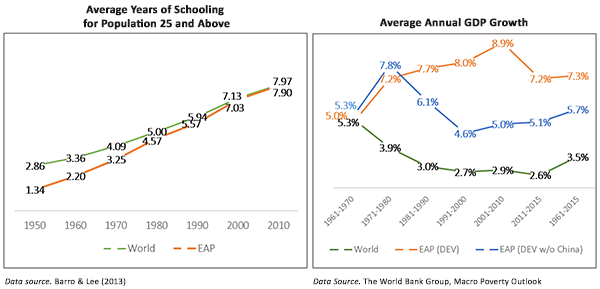

In 1950, the average working-age person in the world had almost three years of education, but in East Asia and Pacific (EAP), the average person had less than half that amount. Around this time, countries in the EAP region put themselves on a path that focused on growth driven by human capital. They made significant and steady investments in schooling to close the educational attainment gap with the rest of the world. While improving their school systems, they also put their human capital to work in labor markets. As a result, economic growth has been stellar: for four decades EAP has grown at roughly twice the pace of the global average. What is more, no slowdown is in sight for rising prosperity.

High economic growth and strong human capital accumulation are deeply intertwined. In a recent paper, Daron Acemoglu and David Autor explore the way skills and labor markets interact: Human capital is the central determinant of economic growth and is the main—and very likely the only—means to achieve shared growth when technology is changing quickly and raising the demand for skills. Skills promote productivity and growth, but if there are not enough skilled workers, growth soon chokes off. If, by contrast, skills are abundant and average skill-levels keep rising, technological change can drive productivity and growth without stoking inequality.

East Asian leaders knew high-quality education was the best way to secure a growing number of good jobs. So for more than six decades they provided education, expanding coverage and improving quality. They continue to provide it in ways that are effective and innovative. Countries now increasingly look to EAP to understand how to make their education systems succeed. A new flagship report from the World Bank—to be released in Fall 2017—will distill key lessons for countries seeking to emulate this path.

One of the report’s main themes is the close connection between education quality and successful sustained growth. Simply providing more education is not enough; policy needs to pay great attention to student learning. EAP countries met the challenge of closing that gap at a time when global average years of schooling per person were tripling. But it is not only the quantity of schooling that matters.

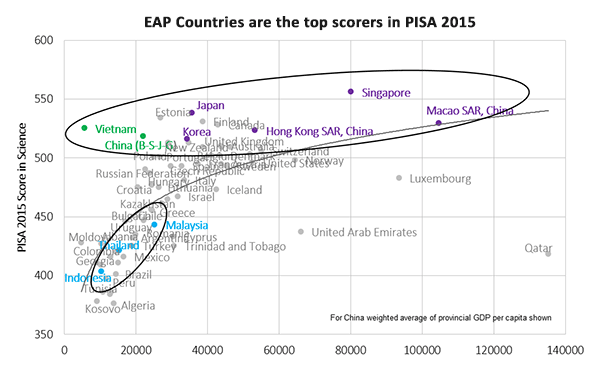

If you don’t learn much in school, you won’t have many skills to bring to your job. What makes East Asia’s achievement even more remarkable is that in many countries the quality of the education provided in this massive “catch-up period” appears to be as good as or better than what the world’s advanced economies were providing. While we do not have measures going back to the 1950’s, in 2015 East Asians students from China and Vietnam—two countries that account for two-thirds of the world’s students--scored above the OECD average in science on PISA, and had 50% more students in the top two performance levels.

Their significant investments have paid off through growing labor market opportunities. In general, an extra year of schooling raises an individual’s earning by about 10%. During the second half of the 20th century, hundreds of millions of people attained several billion additional person-years of schooling, and what they learned was, in general, applied productively at work. While a great many people in EAP still lack access to high-quality, challenging jobs that test their knowledge and skills, more and more workers have this type of work.

Many countries dream of being middle-class societies, where most if not all people have the chance to acquire skills and earn a decent living, and where gaps between the richest and the poorest are modest. The developing countries of the EAP region still have work to do to achieve this vision. But perhaps more than anywhere, they have put themselves on the path by making massive strides to raise both the quantity and quality of schooling.

Join the Conversation