Pemandangan dari udara dari kawasan hunian tetap bagi warga yang terdampak bencana di Duyu, Sulawesi Tengah. Sumber: Kementerian Pekerjaan Umum dan Perumahan Rakyat, Pemerintah Indonesia

Pemandangan dari udara dari kawasan hunian tetap bagi warga yang terdampak bencana di Duyu, Sulawesi Tengah. Sumber: Kementerian Pekerjaan Umum dan Perumahan Rakyat, Pemerintah Indonesia

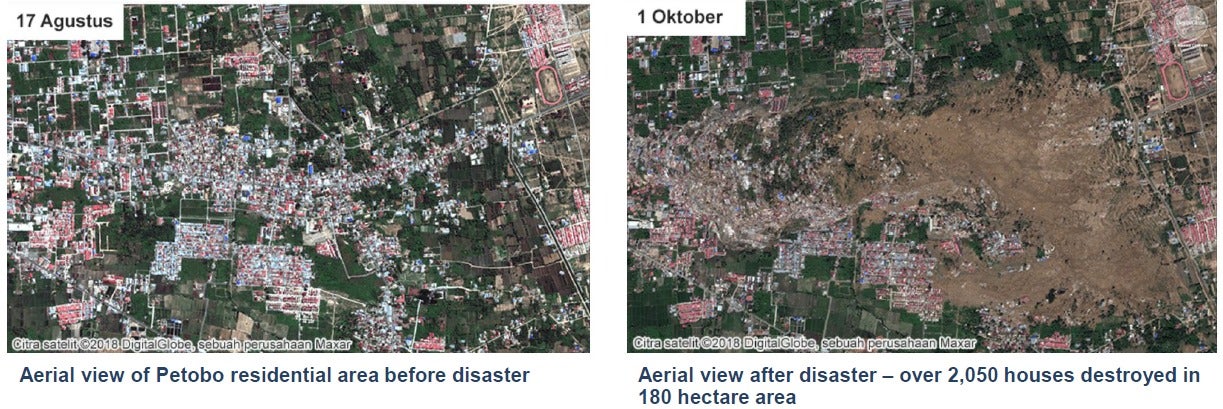

On September 28, 2018, Indonesia’s Central Sulawesi province was struck by a series of cascading natural hazards. An afternoon of foreshocks culminated in a magnitude 7.5 earthquake that caused some of the most severe soil liquefaction observed globally. Residential neighborhoods were swallowed whole.

the significant liquefaction. Source: https://blog.maxar.com/for-a-better-world/2018/satellite-imagery-helps-indonesian-earthquake-victims

The seismic event triggered multiple tsunami waves, reaching Palu City within six minutes of the earthquake. In some places, the water reached nearly six meters in height, destroying low-lying homes and coastal infrastructure.

The disaster resulted in more than 4,400 deaths, 170,000 displaced people, over US$500 million in damages, and US$1.3 billion in losses – an estimated 13.7 percent of Central Sulawesi’s regional GDP. Since then, the government of Indonesia and the World Bank have partnered to rehabilitate, reconstruct, and “build back better” through the Central Sulawesi Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Project (CSRRP) and the Contingent Emergency Response Component under the National Slum Upgrading Project (CERC-NSUP)

to a column at Tadulako University, December 2019.

Photo: World Bank/Jian Vun

Lesson 1: Balance agility with long-term resilience.

Using remote-based damage estimations, governments can quickly identify key investment needs and generate inputs for more detailed assessments . In Central Sulawesi, the team used the World Bank’s Global Rapid Post-Disaster Damage Estimation (GRADE) methodology to swiftly piece together an overall picture of the disaster impacts. This information helped facilitate efficient resource mobilization and additional technical assistance.

For example, technical assistance supported by the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) has produced risk profiles, vulnerability and fragility assessments, and hazard modeling – all crucial information to build back better, increasing resilience to future disasters in the long term. In Central Sulawesi, this is resulting in the reconstruction of buildings to contemporary seismic design standards, complemented by a capacity building program on seismic strengthening good practices. One major lesson learned was to share retrofitting techniques with CSRRP engineers and contractors alike using practical handbooks on vulnerability assessments and decision-making processes, through technical training supported by GFDRR.

Lesson 2: Streamline, integrate, and coordinate from the start.

Recovery programs need to be cross-jurisdictional, inter-organizational efforts involving line ministries, development partners, NGOs, communities, and private sector actors. Institutional arrangements should be established early, and global experience shows that it is good practice to have a single agency coordinating, and in some cases, implementing the recovery program. This helps to coordinate multiple partners and financing sources, matching funding availability with community needs.

Data is one key area in which integration and collaboration is vital. Early in the Central Sulawesi recovery process, various organizations carried out data collection and analysis independently. Information changed constantly. Eventually, the government developed a collaborative online information system, through which all information about recovery activities that can be updated and monitored regularly.

Lesson 3: Put people’s needs at the forefront.

From land rights to universal accessibility standards to resettlement, the key is to engage, engage, engage. A major lesson learned was establishing a dedicated task force for land issues. The updated hazard maps required communities in high-risk liquefaction and tsunami zones to be relocated. However, the sites selected for new permanent housing were being informally used as quarries and plantations, and there were overlapping land claims. The government mobilized community facilitators to engage with disaster-affected people and encourage an inclusive process of relocation through participatory stakeholder consultations and relocation on a voluntary basis only. The result was a more seamless process with opportunities to provide feedback so the system could be continually improved.

CSRRP has also helped to ensure gender-based violence (GBV) risk mitigation is a top priority in Central Sulawesi disaster recovery, including through support from the GFDRR . A field-based expert is strengthening stakeholder capacity for GBV risk mitigation and management through contractor training and enhancing partnerships with local service providers. Under CSRRP, civil works contractors are responsible for mitigating GBV risk through socialization, training, and managing grievances.

Finally, diverse groups should be involved in the entire life cycle of post-disaster recovery – regardless of age, ability, and gender. Addressing inclusion at the outset helps reduce future barriers for vulnerable groups and mitigates social issues. For example, the original design of the housing unit for disaster-affected communities in Central Sulawesi afforded limited privacy. After capacity-building on inclusive design standards, stakeholders modified the design to include an internal partition. In addition, GFDRR support helped to develop practical audit checklists for universal design to evaluate damaged buildings and improve accessibility for all.

Photo: Jian Vun / World Bank

Lesson 4: Turn roadblocks into building blocks.

Recovery efforts generate a lot of debris waste. Roads are cleared; damaged buildings are demolished; destroyed infrastructure is carted away. But reconstruction also presents an opportunity to reuse this waste sustainably. Wood and timber can be repurposed; brick and roofing sheets can be reused; and concrete and rubble can be crushed into aggregate.

In Central Sulawesi, around 80 percent of the debris was material that could be recycled – a total of 540,000 tons of concrete, brick, sand, and soil. Recycled disaster waste material is particularly well suited to rehabilitating and reconstructing roads, buildings, and ports. Using recycled debris can also help meet local demand for building materials.

We hope these lessons will prove valuable in post-disaster contexts worldwide. In the meantime, we’re applying our knowledge from the past three years as we continue supporting communities in Central Sulawesi to becoming more resilient to future disasters – not only for the next three years but for decades to come.

Related:

Join the Conversation