Modern skills and workforce development systems need to provide skills that meet changing employer demands and local job market needs. Copyright: Arne Hoel/World Bank

Modern skills and workforce development systems need to provide skills that meet changing employer demands and local job market needs. Copyright: Arne Hoel/World Bank

Due to automation, climate action, digitalization, and the evolving labor markets about 1.1 billion workers will need to be retrained in the next decade. Many workers will need to change occupations frequently, be ready to offer their skills in the global labor market, and constantly reinvent their professional career paths.

This evolution in labor markets will require skills and workforce development systems to become more personalized, accessible (allowing for remote and hybrid learning), and continuous throughout workers’ careers—placing a “skills-centered” approach at the heart of these global transitions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Adjustments required by education and training systems to meet global megatrends

Skills and workforce development paradigms are shifting

Global megatrends will shift some paradigms of the existing skills and workforce development systems, notably:

1. Investments in youth will render a higher economic return. Recent empirical analysis indicates that human capital investments have high economic returns throughout childhood and young adulthood. Since a significant share of unskilled youth is already out of the formal education system and will account for a large share of the workforce in the next decades, investments in youth skills and workforce development will render high economic returns.

2. Years of schooling will become a less reliable proxy for skills development, since these do not represent the quality and relevance of the skills acquired.

3. Skills (and skills credentials) may take prominence over some degrees. Tertiary education remains highly relevant, as indicated by high returns, but globally some firms, especially in the ICT sector, are dropping some degree requirements to expand their talent pool.

4. Non-formal education will become critical for workforce development. Development of skills will more often occur outside formal education systems, mainly on the job and through short workforce development programs.

5. Enterprises will have a more prominent role in training and re-training. Employers are the consumers of the labor force’s skill set and are a source of skills development. The enterprise sector will need to play a more significant role in providing skills development opportunities for the workforce.

6. Technical and specialized skills will depreciate faster. The rapid pace of technological advancements and evolving labor markets can make technical and specialized skills quickly outdated. On the contrary, transferable skills, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and adaptability, will become more transferable and resilient to changes in the job market.

7. Employment transitions will become more frequent. Individuals globally will have multiple jobs throughout their working lives. According to the World Economic Forum, young people entering the workforce today can expect to have an average of 12-15 jobs over the course of their working lives (e.g., a new job every 3 to 4 years).

8. Workers will need to learn to navigate more complex informal labor markets. A significant share of the labor force in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) work informally, and many of them may never have access to formal employment.

9. Digital skills will render higher value. Digital skills will become cornerstones for successful education and workforce development systems. Digital technologies can offer opportunities to access training, allowing more people to learn regardless of their location or socioeconomic background. Nevertheless, these opportunities are not accessible to individuals, especially in developing countries, who lack connectivity, limited access to computers or smartphones, and inadequate digital skills.

To advance in their careers, individuals must cultivate comprehensive sets of skills

To succeed in this new global context, individuals will need to develop more sophisticated “skills bundles,” comprised of cognitive and non-cognitive skills. Independent learning skills – including foundational, digital and socioemotional skills needed to learn on the job and in lifelong training – will be essential objectives of formal education programs.

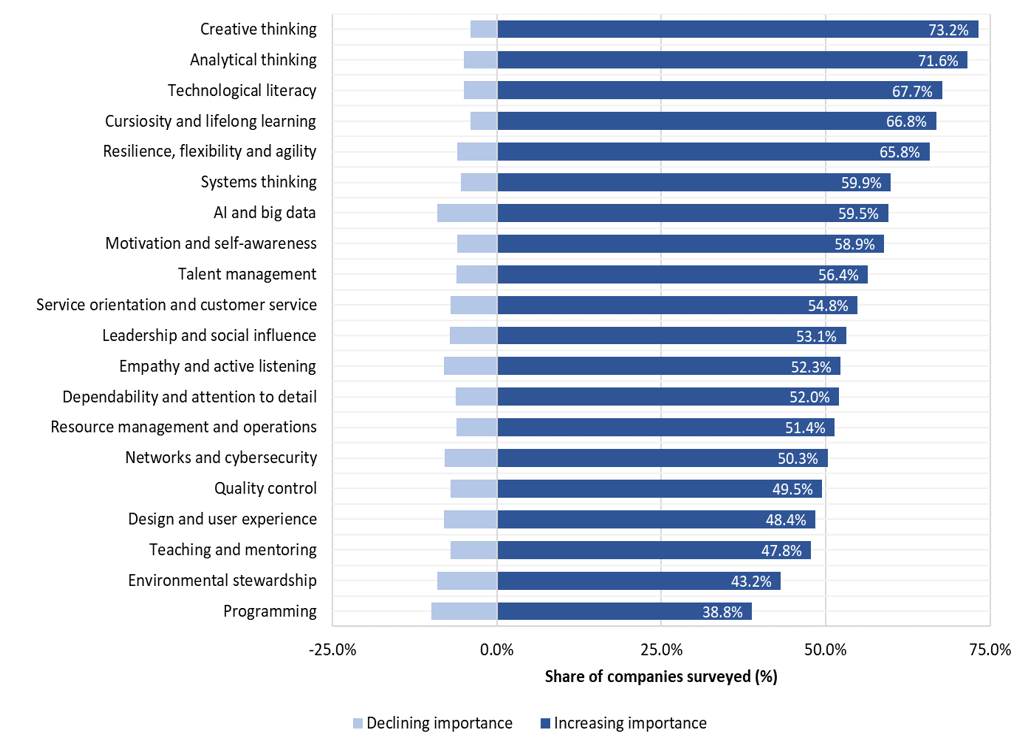

In the past three decades, the relative employer demand for non-cognitive skills has been on the rise, partly because technology has shifted many tasks humans are employed to do away from routine tasks toward tasks that require problem solving, creativity, and analytical skills. Available data indicate that skills such as creative thinking, analytical thinking, empathy, curiosity, and resilience are amongst the top 15 skills demanded by employers globally (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Share of organizations surveyed which consider skills to be increasing or decreasing in importance, ordered by the net difference

Source: The Future of Jobs Report 2023

Supporting effective career transitions

Finally, it is crucial for modern skills and workforce development systems to provide skills that meet employer demands and local job market needs, ensuring that learners can secure employment. Also, assisting individuals during transitions from school to work and between jobs has become a key component of successful training systems. These transitions can be daunting, but with the right support, information, and career guidance, they can be managed more effectively, leading to quicker and better job market integration.

In summary, education and training systems will need to ensure economic relevance, foster skills holistically, promote economic engagement, and support workers during education and employment transitions. These core functions will be crucial in helping individuals adapt to new environments, acquire new skills, and stay competitive in the job market. Ensuring that training systems impart demand-driven skills relevant to employers and local labor markets is of utmost importance.

To receive weekly articles, sign-up here

Join the Conversation