Students on their graduation

Students on their graduation

As the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has spread across the globe, it has hit hardest in many of the global centers of tertiary education. Emerging tertiary education powerhouses China and South Korea were among those affected first. Within weeks, however, the virus was global, and every continent and nearly every country had to react. The immediate actions were roughly the same at world-class universities, technical colleges, and all forms of tertiary education provision in between: shut down campuses; send students home; deliver instruction remotely, where possible; accept a lost academic term where remote delivery is not possible. In few countries was the tertiary education sector able to respond by utilizing a well-informed, already prepared playbook for rapid closure of its physical plant. So, today, the world finds 99% of all formally enrolled students in tertiary education affected. In effect, these students are serving as part of a global experiment, with a wide variety of modalities being tried (with differing levels of effectiveness and quality) for continued provision of their tertiary education.

Three main equity implications are emerging in this first flush of change brought about by the pandemic: lives have been uprooted and left unmoored; the digital divide exposes the socioeconomic inequity of distance learning; and there is a disproportionate likelihood that under-served and at-risk students will not return when campuses reopen. Recognizing these equity challenges as early as possible should allow institutions and governments to fashion interventions that mitigate the impacts and environmental barriers to students’ returning to their studies.

Students’ lives, not just their academic programs, have been disrupted

When their campuses closed, many students were forced to leave their dormitories and hostels. For many, especially those from lower economic groups or unsafe, unstable, or nonexistent family environments, these residence halls are home. Many students rely on their campus facilities as primary sources of meals, health care, and support services, including academic and mental health counseling. Moreover, many students work either on campus or locally, to earn money to cover expenses. The ecosystem that supports their academic commitments also provide a well-rounded life experience for millions of students, in countries at all income levels. In many cases, institutions did not have the capacity to intervene to support their most vulnerable students, who were left adrift. While the scale and quality of campus provision varies widely across regions, countries and institutions, for many students, it is their home. So, all over the world, the loss of this community upends students’ lives and may have lasting negative effects on these students and their families.

The digital divide has been exposed

Online and distance learning has forced massive adaptation for tertiary education institutions regarding how information and coursework is delivered, strongly impacting how (and whether) students learn. There is, however, an implicit bias in this move, which assumes and requires a level of technical capacity, hardware and infrastructure, that is simply not the reality for students around the world. Instead, the move to remote learning has left literally millions of students without any accessible options for continuing their studies after leaving their campuses.

There is a widespread assumption that tertiary education is easily adaptable to a remote learning, but why should this be? Students enrolled on relatively well-resourced campuses—fully equipped with technology and infrastructure—return home to the same neighborhoods as their primary and secondary school neighbors. For many places, there is insufficient infrastructure, and homes lack the hardware and connectivity for distance learning. Moreover, tertiary education is a largely bespoke endeavor, where students craft their academic calendar according to their interests and fields of study and where the quality and opportunities are driven by research infrastructure and direct interactions between research and teaching. Such academic work cannot be delivered by radio or television, as is an option for younger students.

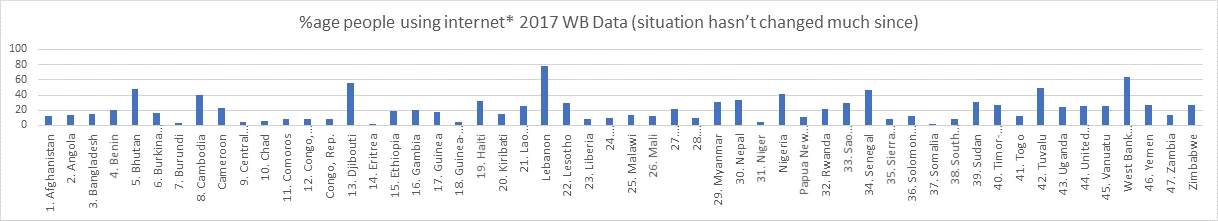

Globally, there is a massive regional variation in internet penetration, with Africa having the lowest, at 39.3% and North America the highest, at 94.6%. Even across fragile and low-income countries, there is massive disparity. As evidenced in Image 1 below, in some of the poorest countries, such as Niger and Somalia, internet connectivity is a luxury, reaching less than 10% of the population. Where internet is so inaccessible to the overwhelming majority of a population, distance delivery of education via online or mobile platforms in worse than inadequate—it is elitist and distortional in terms of expanding inequity.

Image 1. Global Internet Accessibility by Region

Persistence rates are likely to diminish

Perhaps the most significant unknown about this pandemic—particularly in the recovery and resilience phases to come—is how the break in the academic year and the shock to the student experience will impact retention and persistence rates, particularly among already at-risk populations. This includes students who are lower-income, female, of underrepresented ethnic or minority groups, from rural areas, as well as those with mental health or learning challenges or physical disabilities. Students who took a risk to leave home initially, who are not able to remain academically active or are falling behind better connected classmates, or who were employed at or near school and have had to take on new jobs in new locations—all will find it hard to uproot themselves once again and return to school when the pandemic restrictions are lifted.

A recent study of first-degree students in the United States (March 2020, simpsonscarborough.com) found that 20% did not expect to return to the institution they left due to the pandemic closures. Many reported that they may enroll at an institution closer to home, but others will be unable to return to their studies at all. For vulnerable groups, the sacrifices and trade-offs required to achieve enrollment in tertiary education initially may not be sustainable in the aftermath of the personal and financial shocks the pandemic is causing. It is imperative that institutions and government leaders commit to supporting these at-risk students and find avenues for them to continue their studies. Otherwise, they risk becoming secondary victims of the pandemic and its fallout.

Equity in tertiary education is a challenge even in the best of times. The crisis triggered by COVID-19 and likely exacerbated by a recession will undoubtedly stress the most vulnerable even more. Stakeholders who are in a position to prepare for the equity implications should begin now, identifying at-risk students and communities and engaging with them, to understand and respond with support that can help them continue their studies. This crisis has the potential to expand inequities in tertiary education on a global scale. It is imperative to devise interventions that improve students’ persistence and retention. This is a task for governments, institutions, development partners, and individuals alike. While tertiary education institutions are first responders when it comes to at-risk students, governments need to support and complement their efforts through equity-oriented policies, frameworks, and targeted funding.

Join the Conversation