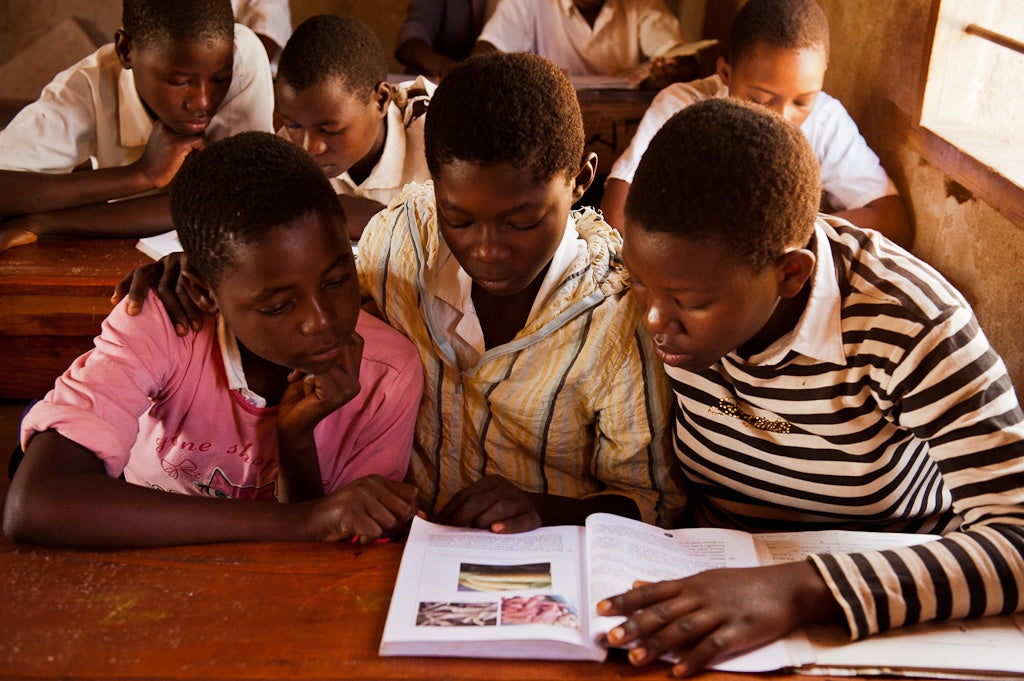

Despite current social and economic challenges, providing high-quality education for all must remain a political priority in all countries. Copyright: Arne Hoel/World Bank.

Despite current social and economic challenges, providing high-quality education for all must remain a political priority in all countries. Copyright: Arne Hoel/World Bank.

Today marks International Day of Education. It is a day to mobilize political ambition, actions, and solutions to recover learning losses due to the pandemic, while recognizing that even before the pandemic, we lived in a learning crisis.

Today, more than ever, we need to spark national and global efforts to end learning poverty. About two-thirds of children globally are in learning poverty. That is, they are unable to read and understand a simple text by the age of ten. That is unacceptable and a threat to the growth and development prospects of many countries. In most countries, the right to education is enshrined in constitutions and is a visible part of all political platforms. But in most middle- and low-income countries, this right is, at best, only partially fulfilled. In some cases, low quality education leads to poor student outcomes, and in others, basic education is not free or the education experience is interrupted by protracted conflict.

Are we getting it?

The problem is not that we don’t know how to set up a good school and a decent education system. Good examples abound. The problem is the lack of political will and an understanding of how big the problem actually is. A 2021 paper by Lee Crawfurd et.al of the Centre for Global Development showed that public officials in 35 countries underestimated the share of 10-year-olds in their countries who could not read and understand a simple text. They said that on average, the figure should be 25%. The reality was 47%. This may explain why there is often no sense of urgency or low prioritization of education in budget decisions.

As policymakers underestimate the magnitude of the challenge, it should not be a surprise that expenditures per pupil are insufficient to provide a decent education for all. According to the 2022 Education Finance Watch by the World Bank and UNESCO, annual expenditures per pupil in basic education in high-middle income countries are $1,080, while it is an appallingly low $53 in low-income countries. These numbers pale compared to the $7,800 observed on average in OECD countries. Prices differ across countries, but even with those differences, it is impossible to ensure a decent education with such low expenditures.

The human factor

More financial resources are needed to hire and pay teachers, for infrastructure, digital resources, teaching material and teachers’ professional development, particularly in low-income countries. But there is also space for improving efficiency. For example, books, buildings, and tablets can be purchased more efficiently (in low-income countries, 30% of the goods and services line of the budget goes unspent) and in a way that avoids corruption. Technology can support systems management and help make teachers’ work more efficient and impactful. But the most important action to improve efficiency is to make sure that the people working in schools and managing the system are the best and perform at their best.

Expenditures on education personnel comprise anywhere between 60% and 90% of country education budgets, so getting the most out of these professionals is a critical step to improving education. Teachers and education professionals define the quality of an education system. And it is precisely that human factor that defines the quality of an education system. The quality of the learning experience for a child or a young person depends mostly on the quality of the interaction with their teachers. Teachers must be able to inspire students, foster their creativity, teach them how to learn, and develop all their potential. That is not an easy job. Hence, education systems must bring the best professionals to the teaching career.

Regrettably, there are still many education systems where political criteria determines who is selected as a teacher or principal or where the teacher is deployed. When that happens, it doesn't matter how much is invested in books, technology, or buildings, the chances of good quality education are very low. Teachers must be selected meritocratically, and they must be supported with practical training and coaching, and lesson plans where needed, giving them the tools to improve their work in the classroom constantly. And energetic leaders and managers must be selected as principals. Finally, these professionals must be well paid, as they have the future of our children in their hands.

Elevating education as a political priority

A high-quality education for all is not impossible. Still, it requires political and financial commitment, and the commitment to bring the best possible bureaucracy to manage this complex system.

Despite the multiple crises we are enduring and the current social and economic challenges, education must remain a political priority in all countries. Education systems have many needs, and the pandemic has made those needs even more acute. Political leaders, business communities, education communities, and society, in general, must move swiftly and decisively to recover learning and rebuild systems that focus relentlessly on improving the quality of the teaching-learning process. We must address this before the learning losses of the pandemic leave a permanent scar on children’s futures. The time to act is now.

Join the Conversation