“We face neither East nor West; we face forward.” - Kwame Nkrumah (1957)

The facts relating to learning outcomes in many countries in the Africa region are depressing and the challenges are immense. But there is a growing body of new evidence from countries across Africa that points to lessons that can be learned about what has worked to improve learning. Together with my co-authors, Sajitha Bashir, Marlaine Lockheed, Jee-Peng Tan and many other contributors, the World Bank has just released a book entitled “ Facing Forward: Schooling for Learning in Africa” that focuses on how to improve learning outcomes in basic education —i.e six years of primary and three years of lower secondary education.

As part of this study, we compiled and analyzed a mind-boggling number of data sets covering nearly 50 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. We found surprisingly nuanced accounts of the evolution of education systems across countries. We also found that there isn’t a single narrative about education in the region, and this blog explores two such narratives that can be misleading.

The first narrative is that Africa faces a twin crisis of access and learning. Well, this is not true for all countries in the region. Yes, there are an estimated 50 million children of primary and lower secondary school-going age—almost a quarter of all children in that age group— who are not in school at all or who have dropped out of school. And about 40 percent of out-of-school children are concentrated in three of the region’s most populous countries: Ethiopia, Nigeria and Democratic Republic of Congo.

But some countries like South Africa, Kenya, and Zimbabwe (in what we call the “established” group of countries - see figure below) have almost universalized access to primary education over the past two decades, despite many challenges arising from political instability, income inequality and linguistic diversity. Some countries like Namibia and Botswana in this “established” group have even almost achieved universal lower secondary education. Other countries like Uganda, Rwanda and Togo (the ‘emerged’ group of countries), through concerted efforts in the last two decades, have made spectacular gains in access. Countries such as Ethiopia, Benin and Burundi (the “emerging” group) have also made impressive progress on access though there remains a sizable share of children who are still out of school. And there are countries like Chad, Liberia and Central African Republic (the “delayed” countries) that are lagging in access. Many countries in this group have faced challenges related to conflict and political turmoil, which have negatively impacted their ability to develop education systems.

Growth in Access to Primary Education in 44 Sub-Saharan African Countries, by Group, 2000–13

So, back to the narrative: Yes, there is a learning crisis in many countries across Africa. However, the crisis in access is not uniform across the continent. Some countries have achieved universal access to primary education, while in others like Senegal, Niger and Liberia still a need to expand the system to give all children a chance to enroll in school. In countries like Uganda and Rwanda, targeted policies will be needed to draw marginalized communities and individuals into the classrooms. In some countries in the “established” group like Botswana and South Africa, with declining child population growth rates, policymakers can concentrate mainly on improving the quality of education.

The second narrative we hear is that learning levels are going down in the region. Learning levels are indeed dishearteningly low across all countries in the Sub-Saharan Africa region. But is there compelling evidence to suggest that learning levels are declining in the region?

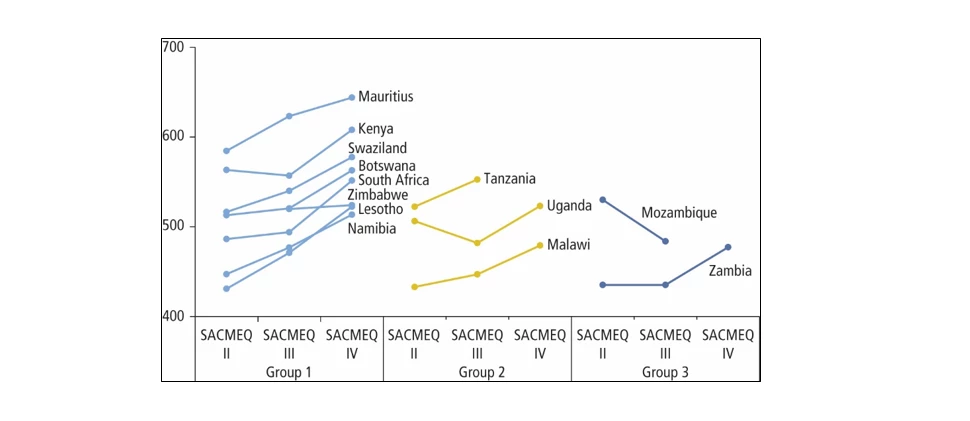

Below is a graph with average scores on a regional learning assessment (SACMEQ) for sixth graders in mathematics in 13 countries in Eastern and Southern Africa. Technically, the scores across these assessments are comparable and, in most of these countries, the average scores increased in the last two assessment cycles in 2007 and 2013. The only exception is Zimbabwe, where the scores are stagnant. As the figure below highlights, there is evidence that points to improvements in learning but even so, in 2013 only a third of sixth-grade students across these countries performed no higher than the “basic reading” and “basic numeracy” levels. So, while the data points to some improvement in learning levels, it’s certainly not sufficient for us to start patting ourselves on the back.

Average SACMEQ Sixth-Grade Mathematics Scores, Participating Southern and East Africa Countries, by Group, 2000–13

Source: Based on data in Bethell 2016; MOEST 2017

Ghana and South Africa have also shown some progress, albeit starting from a low base, with greater shares of eighth or ninth-grade students reaching the low international benchmark for mathematics in more recent assessments in 2011 and 2015. So, again, signs of improvement. But even these countries—the top performers on education access in the region— are only reaching the low international benchmark on learning, which means, the bottom of the scale globally.

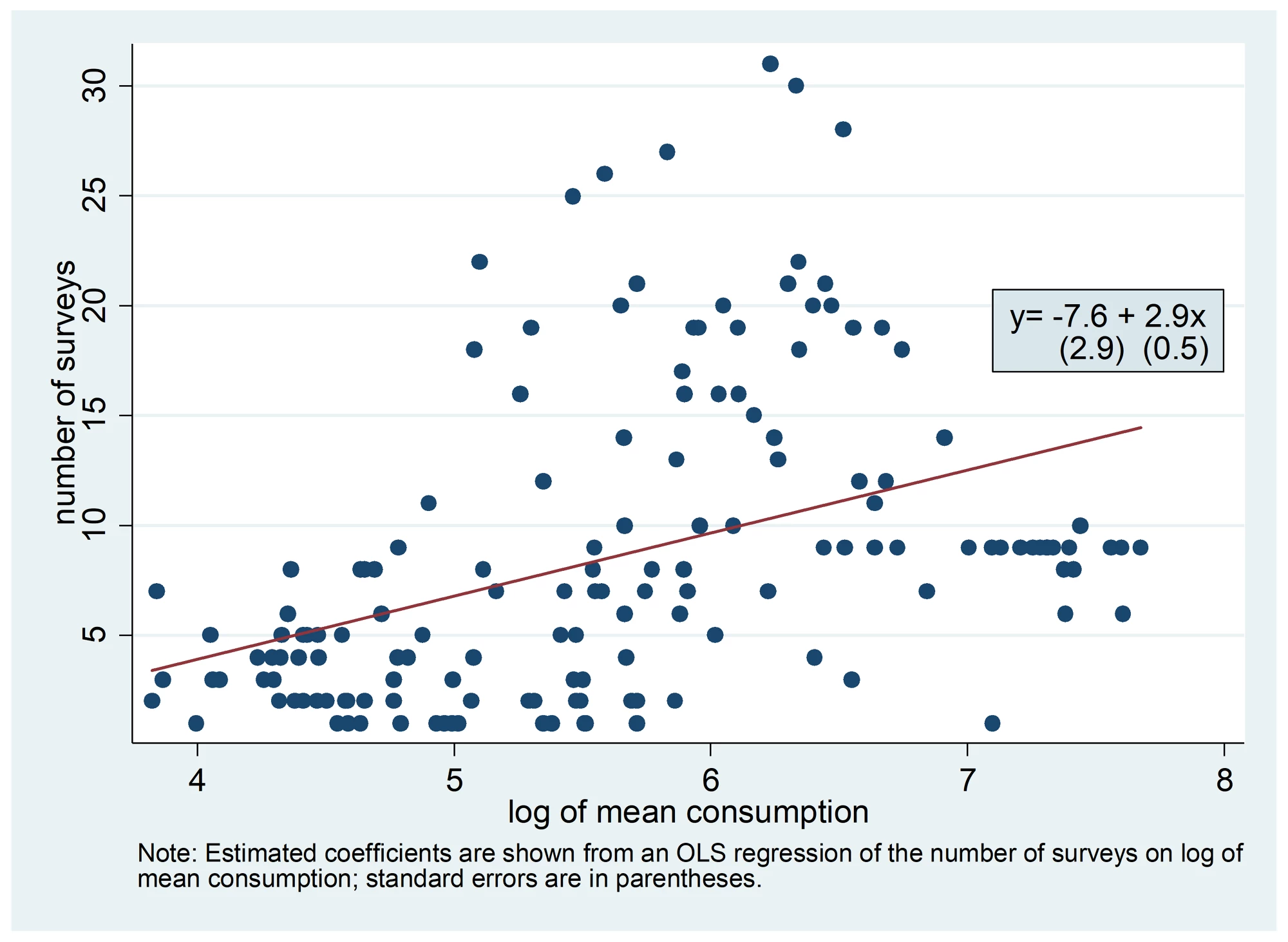

West and Central Africa don’t have learning assessments that are comparable over time. Hopefully, these will become available after the next round of the PASEC assessment in 2019. And while there may be some national learning assessments that show declining learning levels, this should not be an indictment of the entire continent. To assess progress, we need better and more frequent measures that are comparable over time.

Looking ahead with a more nuanced—and accurate— narrative

In our new book, we highlight what can be done to shift the course of learning in Sub-Saharan Africa. We focus on ensuring that children are taught in a language they understand in the first years in school, and on the need for training, supporting and supervising teachers to deliver structured lessons. We delve into the determinants of learning and confirm that there are no clear patterns for what matters to improve learning across the continent or even within parts of the continent. There isn’t one recipe for the continent and policymakers in the region will do well to start building and documenting their own evidence of what works in their specific context. We also showcase what has worked—and in some cases, what hasn’t worked— to improve education outcomes in different countries, including negotiations with teachers’ unions in Kenya, tackling overcrowding and hidden repetition in early grades in South Africa, and documenting some of the reasons why Burundi is an exception to the PASEC assessment trends. There is a lot that African countries can learn from each other and this book gathers critical knowledge from the region that is relevant for the region and beyond.

Find out more about World Bank Group Education on our website and on Twitter .

Join the Conversation