250 million children under the age of five in the developing world are failing to reach their full development potential. Faced with this challenge, governments and donors across the globe have turned to early childhood education and development (ECED) services. These are a cost-effective way to overcome the developmental losses associated with growing up in a disadvantaged environment. The services can be delivered in different ways, such as through kindergartens and community-based playgroups.

But how effective are these, in practice?

In a recent paper, we use both experimental and quasi-experimental techniques to answer this question by evaluating the impact of a low-cost, government-sponsored, community-based ECED intervention on enrollment and child development in rural Indonesia, where kindergarten and private programs were already operating.

The findings from the paper are especially important given recent claims that preschool interventions in developing countries are growing despite considerable variation in both design and results from empirical studies on the topic. Few studies apply a credible evaluation strategy and the majority of evidence isn’t that pre-schools work, but rather that high-quality programs focusing on serving infants, toddlers, and/or families do.

The ECED project we evaluated was implemented in 3,000 villages across 50 disadvantaged districts in Indonesia with low ECED participation. 310 of the villages, spread over nine districts, participated in the evaluation. Each project village received a package of interventions meant to improve children’s school readiness. This included the services of a community facilitator whose job was to raise community awareness on the importance of early childhood services; block grants for three years totaling $18,000 per village to be spent on establishing or supporting two centers; and 200 hours of teacher-training for up to two teachers per center. This package was designed to encourage bottom-up community services that would prove not only sustainable, but well-suited to the needs of each individual village.

Most villages decided to use the block grants to establish playgroups. In Indonesia, playgroups operate three times a week for three hours a day. They also allow children between the ages of three and six to enroll.

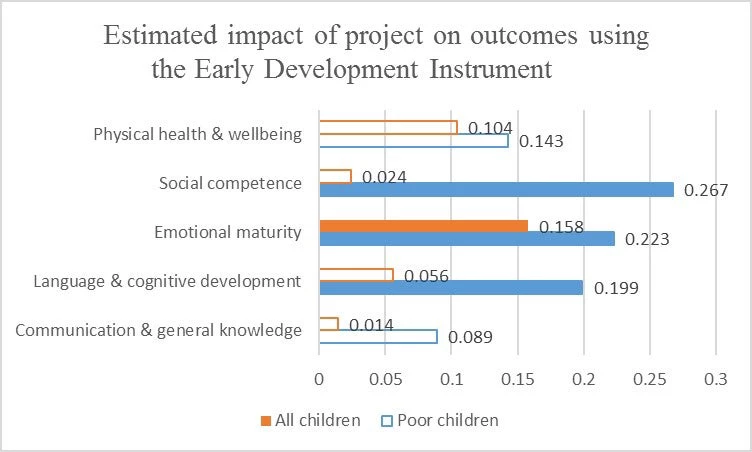

In order to evaluate the impact of the intervention, we investigated the effect of the project on enrollment and on children’s readiness for primary school across five domains: physical health and well-being, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive development, as well as communication and general knowledge.

What did we learn?

Results show that low-cost, government-sponsored, community-based early childhood programs hold promise in producing modest and sustained impacts on child development—particularly for those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

• Enrollment rates rose by seven to nine percentage points, constituting an increase of 35-45%. This is despite the fact that there was considerable substitution away from kindergartens towards the government-sponsored playgroups;

• The intervention led to a net increase in duration of enrollment in ECED in the villages where the program was implemented;

• When the difference in exposure to the ECED intervention is small (between six to 11 months), we find no significant impacts on child development outcomes;

• In contrast, when the difference in exposure is larger (up to 3 years) we find evidence of some positive impacts on social competence, emotional maturity, and language and cognitive development;

• In particular, disadvantaged children – those from poorer households and whose parents reported below-average parenting practices – benefited more from the project; and

• Even three years after the project began, disadvantaged children had significantly larger improvements in social competence, emotional maturity, and language and cognitive development compared with children from more advantaged backgrounds.

See the figure below:

Follow the links for a closer look at our research design and findings.

If you know of similar initiatives, please share in the comments section below.

Find out more about World Bank Group Education on our website and on Twitter.

See our resources on early childhood development.

Join the Conversation